- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Policy Competition and Foreign Direct Investment in Europe

About this book

First published in 1999, this volume recognised how widespread attention has been given to charting how the global rise in investment flows has caused numerous changes in the operation of economies – such as the globalisation of production and increasing international economic interdependency. Less research has been made on the role of government policy in promoting FDI. This book, based on a report for the OECD Development Centre, examines the rising competition between European governments to attract mobile investment projects and its impact on the use of different policy areas to influence FDI decisions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Policy Competition and Foreign Direct Investment in Europe by Philip Raines,Ross Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

PHILIP RAINES AND ROSS BROWN

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has expanded rapidly throughout the world economy over the last two decades. This trend has been promoted by the removal of national barriers to capital movements and increasing globalisation, especially by multinational enterprises (MNEs). The aggregate stock of FDI in the world economy is estimated to have risen from 4.5 percent of world output in 1975 to 9.5 percent in 1994, with the value of sales by foreign affiliates of domestic companies exceeding the value of world exports by around a quarter (Barrel and Pain, 1997). Between 1980 and 1989, accumulated FDI inflows among developed countries were more than four times as large as during the 1970s, with FDI growing faster in the 1980s than GDP and trade by factors of four and three respectively (Neven and Siotis, 1993).

Widespread attention has been given to charting how the global rise in these investment flows has been associated with changes in the operation and inter-relationships of national and regional economies - such as the globalisation of production and increasing international economic interdependency. Less research has been carried out on the impact of rising FDI on government policy, not just on the overall objectives of economic policy, but the types of micro-economic and regulatory policies favoured by governments.

The policy impact is evident at different levels. International responses to FDI growth have included efforts to establish collective frameworks on the treatment of foreign investors, notably the OECD's Multilateral Agreement on Investment and the agreement brokered through the World Trade Organisation on trade-related investment measures (TRIMs). At national level, recognition of the role of foreign investment in regenerating local economies and creating employment has resulted in policies being specially devised for attracting and retaining FDI, involving the coordination of existing policy instruments, the creation of new ones, the allocation of increasing resources to FDI policies and the development of institutional structures for delivering different elements of these policies. The work of national governments has been mirrored by similar approaches taken sub-nationally, as regional governments and local authorities and agencies have pursued their own individual policies in competing for FDI.

In Europe, this process of FDI policy development at different levels has perhaps advanced further than elsewhere in the world. The importance of attracting foreign investment has been acknowledged by local and national governments as well as by larger groups such as the European Union. At the same time, the need to set competition within limits has also been recognised, leading to the emergence of detailed controls on industrial subsidies and incentives at European level by the European Commission. Although the nature of this competition is changing with the continent's realignment in response to the liberalisation and restructuring of the economies of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), policy competition remains the driving force behind the scale and type of approaches to regulating and attracting foreign investment.

The following study addresses the issue of policy competition in Europe by considering three sets of questions. First, it will gauge the level of policy competition in Europe, assessing the extent to which governments in both Western and CEE governments have positive attitudes towards encouraging foreign investment and detailing the main policy areas and approaches used by governments. Second, the question of whether policy competition is increasing will be answered as the study identifies the different factors influencing future changes in FDI trends and likely policy responses to these changes. Lastly, the study will examine the effects of policy competition in Europe: has inter-governmental rivalry encouraged an overall rise in FDI, increased investment in human capital and infrastructure, more open national markets and a more secure legal environment, or has it led to costly 'bidding wars' between countries, involving rising incentive budgets and diminishing labour and environmental standards? More importantly, where competition has produced harmful effects, have systems been put in place to limit the damage caused and control the rivalry?

In addition to this introduction and the conclusions, the study is divided into two sections. The first section sets the policy context for foreign investment competition in Europe in two chapters. The first chapter focuses on Western Europe: recent trends in foreign investment flows, the different approaches of national and European Community policy-makers to foreign ownership of the economy, and the institutional structures that exist to promote foreign investment. Given the substantial differences between FDI trends and policy issues in Western European and CEE countries, FDI policy in CEE is reviewed separately in Chapter 2 (though aspects of it are considered in some of the later chapters, as appropriate).

The second section of the study examines policy competition in specific policy areas, principally in Western Europe, A wide range of policies influences FDI flows, often in areas not directly linked to FDI - eg. local content regulations in trade policy will affect whether external companies locate within a trade area, and macroeconomic policy will determine whether national markets are sufficiently attractive and stable for potential foreign investors. This study focuses only on policies that have been explicitly linked to the regulation and attraction of foreign investment in Europe. Although the policy areas vary in terms of the degree to which FDI considerations have shaped their development - and consequently, the extent to which they can be described as 'FDI policies' they have all had a visible FDI dimension in Europe over the past decade.

The policies can be divided into those which are 'incentive-based', aiming to influence location decisions directly by subsidising the establishment (and to some extent, operating) costs of investment locations - such as regional financial aids and tax incentives - and those which are 'rule-based', which have a more indirect impact on costs by affecting the regulatory and operating environments of foreign investors - such as labour and environmental standards, and controls on the use of financial incentives.

Three final points require clarification. First, for the purposes of this discussion, FDI is defined as 'an investment involving a long-term relationship and reflecting a lasting interest and control of a resident entity in one economy (foreign direct investor or parent enterprise) in an enterprise resident in an economy other than that of the foreign direct investor (FDI enterprise or affiliate enterprise or foreign affiliate)' (UNCTAD, 1996). With the focus on the more direct and longer-term impacts of investment, portfolio investment flows and the policies affecting those flows have not been considered here.

Second, the study will make reference to rules and policies in the 'European Union' and the 'European Community' interchangeably. This reflects the fact that, since the signature of the Maastricht Treaty, the term 'European Union' has entered into common parlance to refer to actions conducted at the European level. Technically, however, European competition, employment and environmental policies remain European Community (EC) policies. These remained substantially unchanged under the recent Treaty of European Union which added two 'pillars' of inter-governmental cooperation and coordination (Justice and Home Affairs and Common Foreign and Security) to the existing EC provisions.

Lastly, the study was finalised by the end of 1997 and consequently, does not discuss in detail more recent developments in certain areas, notably the introduction of proposed codes on tax incentives and the use of financial incentives for large foreign investment projects in the EU.

Part I:

Policy Context

2 FDI Policy Approaches in Western Europe

ROSS BROWN AND PHILIP RAINES

Introduction

In over two decades of active FDI promotion, Western European approaches to attracting foreign investment have been characterised by increasing activity and sophistication in both policy design and delivery. While largely responding to the impact of greater competition between governments at a time of larger FDI flows, the scale and variety of policy responses reflect a realisation that investment promotion requires both the designation of clear administrative responsibilities within government and a more adept use of both incentive- and rule-based approaches to attracting FDI. Hence, at the same time as European countries have defined comprehensive national policies on foreign investment, they have developed institutional mechanisms for delivering different aspects of FDI policy. Hardly anywhere in Western Europe currently regards the attraction of FDI projects as an ad hoc policy activity: virtually every European country has considered FDI sufficiently important to warrant a set of specific policies and organisations (although with widely varying degrees of priority).

In this chapter, the policy context for the whole of Western Europe is considered, providing a background for understanding the scale and effects of policy competition. Following this introduction, the statistical context of FDI policy is reviewed in the second and third sections, through a summary of the main investment trends in Western Europe in recent years and the current and likely future factors determining these flows. The fourth and fifth sections focus on the strategic context of policy by examining the importance of foreign investment as a goal for Western European governments, both from the perspective of the differing national as well as European Community approaches to the regulation of foreign ownership in the economy. Finally, the institutional context is analysed with respect to the organisations promoting foreign investment and the approaches developed by inward investment organisations at national and local levels.

Foreign Investment in Western Europe

The United States remains the country receiving the largest inward investment flow - US$ 85 billion in 1996 (UNCTAD, 1997). As a region though, Western Europe is currently the main destination for worldwide FDI. Inward flows were US$ 105 billion in 1996, accounting for about a third of global inward investment. Its share of the global stock of FDI has been increasing over the past decade, rising from 33 percent in 1985, peaking at 44 percent in 1990 before falling back to 40 percent in 1996.

Several distinct geographical features characterise current FDI flows in Western Europe. Although short-term FDI inflows fluctuate quite substantially, the spatial distribution of FDI seems quite fixed over the long term and these patterns appear to be part of longer term trends where certain countries and regions dominate Western Europe's FDI inflows.

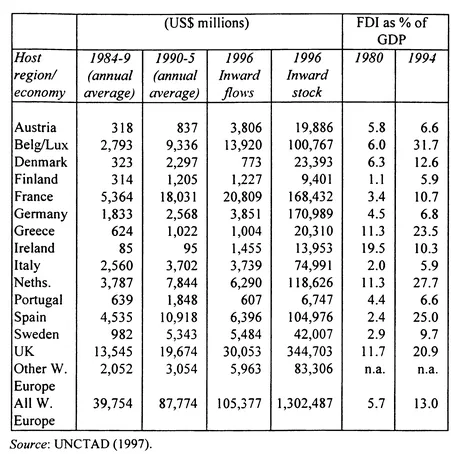

Three countries - the United Kingdom, Germany and France - account for over half of the stock of FDI in Western Europe and annual average inflows during the 1980s and 1990s (Table 2.1). The Western European country which has undoubtedly been most attractive to incoming FDI is the UK. The historical pattern of Europe's FDI flows shows that the UK is consistently the most important investment location, both in terms of stocks as well as recent inflows. This has been particularly true in terms of non-European FDI, as the UK has attracted 40 percent of US FDI in Europe and more than 40 percent of FDI from Japan and Asia's tiger economies. In global terms, the UK continues to be the world's second largest recipient of inward investment after the US (UNCTAD, 1997). Reflecting the openness of the economy, sales of British businesses to overseas investors were estimated to have exceeded the total for all other EU countries combined during 1996 (IBB, 1997).

Table 2.1 FDI in Western Europe

Inward investment is largely concentrated in the northern, more developed countries in Western Europe. In recent years, one of the most important locations for FDI has been France, which had FDI inflows totalling US$ 20.8 billion in 1996, a figure which places France second in Western Europe's league of FDI. Indeed, in terms of flows, France briefly overtook the UK as Europe's top destination for incoming FDI in 1994.

Not surprisingly, Germany is another major destination for FDI, though its importance appears to have diminished in recent years. Although Germany has the second largest FDI stocks in Western Europe, its inward flows seem to have declined sharply in recent years, so that in spite of being the largest economy in the region, it only received 3.7 percent of FDI flows in 1996, leaving the country with one of the lowest FDI-to-GDP ratios (Table 2.1). Moreover, these inflows have been dwarfed by the massive FDI outflows of US$ 28.6 billion (UNCTAD, 1997). Germany's imbalance between outflows and inflows reached US$ 24.8 billion in 1996. While some commentators note that the difference may have been exaggerated by distortions arising from Bundesbank data-gathering (Dohrn, 1996), fears have been regularly cited of a potential 'hollowing out' process in German industry (see, for example, Tuselmann, 1995).

Interestingly, some of Europe's smaller economies are also major recipients of incoming FDI, particularly Belgium-Luxembourg and the Netherlands. In fact even during the early 1990s when Europe's FDI flows were subdued, some smaller European countries experienced increasing FDI flows (eg. Belgium-Luxembourg). Average flows for Belgium-Luxembourg between 1990-95 were over treble what they had been between 1984-89 (Table 2.1). The Netherlands has the fourth largest stock of foreign investment in Western Europe, accounting for nine percent of the total stock. FDI as a share of GDP is also high in these small, centrally-located countries. Foreign investment in Belgium-Luxembourg comprises almost a third of GDP and over a quarter in the Netherlands, underlining the importance of FDI for these small, open economies.

Sweden has also seen very rapid increases in FDI inflows in recent years. At US$ 5.4 billion in 1996, FDI inflows in Sweden are the sixth highest in Western Europe. Although Sweden has been a large source of FDI outflows for a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- Part I: Policy Context

- Part II: Policy Competition

- Bibliography

- Appendix: Note on Foreign Investment Statistics