1.1 Introduction

This study deals with an important informal sector activity. Urban agriculture is important, especially since many urban residents in developing countries rely on town/city agriculture in one way or another. One of the most important needs of urban people in developing countries is food. In recent past, food for urban residents came from rural areas, however, due to various reasons the food supply from rural areas is inadequate for many towns/cities in the developing world, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

In 1981, the World Bank observed that,

... for most African countries, and for a majority of the African population, the record is grim, and it is no exaggeration to talk of crisis. Slow overall economic growth, sluggish agricultural performance coupled with rapid rates of population increase, and balance-of-payments and fiscal crises—these are dramatic indicators of economic trouble (World Bank, 1981:2).

Writing on the economic and food crises on the continent, Hansen (1989) confirmed the position of the World Bank by noting that ‘it is now easily conceded even by the most optimistic observer that Africa is in the midst of a severe [food] crisis’ (Hansen, 1989:184).

More than a decade later, in 1998/1999, one could still make such an observation about stagnant, if not decreasing, economic conditions in sub-Saharan Africa. As noted elsewhere, in present-day sub-Saharan Africa, ‘rural areas do not produce enough food to feed both rural and urban people and importation is constrained by lack of sufficient foreign exchange’ (Sawio, 1994:25). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) notes after praising a few African countries for improving their economic conditions that ‘in a number of other [sub-Saharan African] countries... economic conditions remain difficult (IMF, 1996:11).

The seriousness of the poor economic conditions reported for sub-Saharan Africa is compounded by the trend of population growth in that area. Over the years there has been a high population growth coupled with decreased productivity. This trend implies the dire need for programmes to improve upon food production on the continent because ‘it is in the field of agriculture that the crisis manifests itself in its most virulent form’ (Hansen, 1989:186). It is an uncontroversial fact that in sub-Saharan Africa food sufficiency ratios have dropped since the 1960s. According to an observer, ‘by 1980 food self-sufficiency ratios had dropped from 98 per cent in the 1960s to around 86 per cent, which means that each African has on average 12 per cent less grown food in 1980 than 20 years ago’ (Hansen, 1989:186).

The situation is not better in the 1990s. According to Svedberg (1991), the per capita availability of food has declined over the 1970s and 1980s and is now below 80 per cent of FAO/WHO recommended per capita intake. In 1994 Pinstrup-Andersen observed that ‘many Africans are worse off today than they were a decade ago’ (Pinstrup-Andersen, 1994:6). While food sufficiency ratios have dropped, the demand for food has gone up as a result of population growth, especially in urban areas. Food insufficiency in urban sub-Saharan Africa is mostly caused by a combination of factors including, as already noted, inadequate food production in rural areas, faulty government policies, poor distribution and storage facilities, farmer alienation due to the use of crude implements, and a concentration on export or cash-crop production to the detriment of food-crop production.

Food scarcity in sub-Saharan Africa is compounded by increased urbanization and proletarianization, which has removed a significant number of people from the traditional agrarian sector which feeds the population. The World Bank, as well as the United Nations (UN), has noticed a high urban population growth in sub-Saharan Africa. The UN, for example, estimates that between 1995 and 2000 the annual rate of change of the urban population in Africa will be about 4.72 percent per year (United Nations, 1995). In Ghana, the urban growth for 1995-2000 is estimated at 4.62 per cent as compared to 3.0 per cent for the country as a whole (UN, 1995).

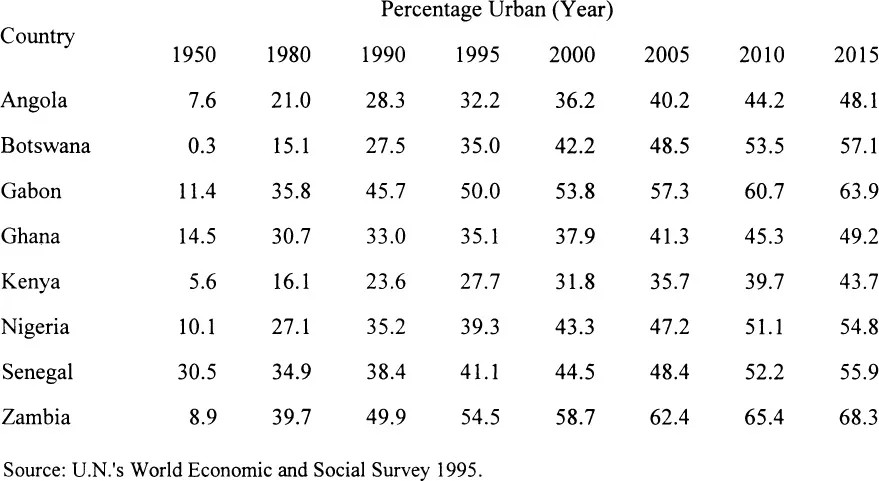

Table 1.1 Actual and Projected Urban Population in Some Selected African Countries

Table 1.1, which is self-explanatory, shows that an increasing number of sub-Saharan Africans are moving into urban areas, thus making it more necessary for programmes that increase food production.

Urbanization influences domestic food production and consumption depending on the region in question. In developed countries, increased urbanization does not necessarily lead to a decrease in the quantity of food produced. This is due to the use of improved agricultural machinery, which makes it possible for a few farmers to produce enough to feed the population. In developing countries, however, most of the cultivators still use crude farm implements which limits the number of acres an average farmer cultivates. Thus, the fewer the number of farmers, the lesser the amount of food produced. Therefore, increased urbanization may lead to food shortages due to the migration of farm labour from the countryside.

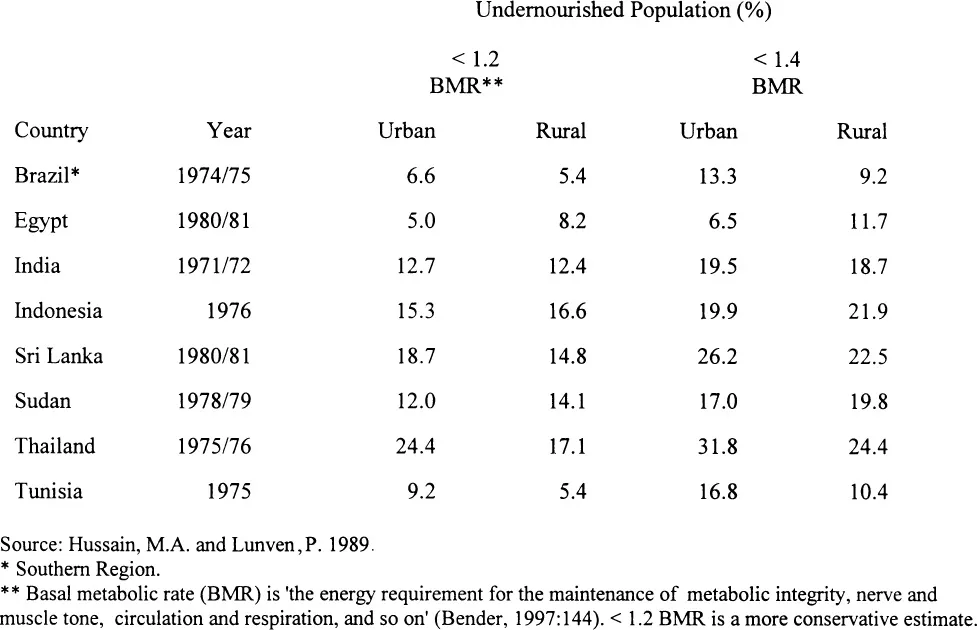

The introduction of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAP) in various parts of sub-Saharan Africa and the attendant labour redundancy, which this has produced, have compounded the precarious economic condition for many people, especially urban residents. Employment and wages play a central role in determining the food security of urban households. Without wages, urban residents may not be able to purchase food. The urban unemployed are therefore in crisis because their sources of cash income and consequently their foremost survival base has been denied them. Unemployment, indeed poverty, leads to insufficient food consumption. As Table 1.2 shows, in developing countries undernourishment is higher in urban than in rural areas.

The above table indicates that urban food insecurity and malnutrition abound in developing countries. In most sub-Saharan African countries, official rural agricultural programmes put in place to alleviate this economic hardship have so far not been successful. Consequently, individual urban dwellers have resorted to their own strategies to feed themselves. One such strategy is urban agriculture.

Urban agriculture is a significant part of the informal sector of the economy of most sub-Saharan countries. To define the concept of informal sector, it is almost always contrasted with the formal sector. The concept attracts different conceptualizations because of ‘the lack of a clear theoretical basis for the concept as well as wide spectrum of economic activities that it covers’ (Singh, 1994:7). In this work, I use the concept of informal sector in reference to the economic activities with the following characteristics: casualness, easy entry, outside the scope of existing company law or government regulations, small-scale operation, reliance on household labour, and labour intensive. This means the informal sector excludes public sector establishments, as well as large-size and commercial establishments in the private sector. The informal sector is a veritable superstructure for the survival of the formal sector of developing economies. As Leys (1975) observes, the existence of the informal sector [to which urban agriculture belongs] is essential for the profitable operation of the formal sector of most national economies. It provides cheap goods and services for poorly paid workers. In addition, it sustains the reserve army of workers for eventual employment by the government and Capitalists. Conversely, the formal sector is necessary for the survival of the informal sector. Therefore, the two sectors ‘must not be considered as separate dimensions of national growth, but rather as two closely interrelated facets of a single issue, i.e. the investment and organization of natural resources’ (Dettwyler, 1985:426).

Table 1.2 Extent of Undernutrition in Selected Developing Countries

Due to the implementation of Structural Adjustment Programmes by many African countries, as mentioned above, formal employment is frozen in the public sector.1 Consequently, the formal sector is not able to guarantee a minimum level of employment. The informal sector has therefore become ‘a welcome outlet both for individual citizens grappling with unemployment and for governments happy to observe that unplanned solutions can arise to fill gaps in planning and public policies’ (Stren et al, 1992:29). Also commenting on the employment importance of the informal sector of the [Ghanaian] economy, the Institute of Statistics, Social and Economic Research (ISSER) mentioned that,

alternative means of employment in the formal sector have not by any means kept pace with the redeployments and increase in the urban labor force, leaving most job-seekers no alternative to the informal economy, and the number of workers in the urban informal sector has mushroomed (ISSER, 1995).

An informal sector activity like urban agriculture provides jobs for many urban farmers, as well as artisans, who provide farmers with implements like hoes, animal pens, and fences.

In spite of its significance in national economies, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa have no official policy on urban agriculture. In fact, in countries like Ethiopia, Uganda, Cameroon, Zimbabwe and others, farms in towns and cities have often been destroyed and livestock confiscated by the political and municipal authorities in town or urban planning processes. However, there is evidence that such ‘harassment of urban cultivators has declined in recent years due to the increasing fluctuation in food supply in urban areas from rural subsistence economies’ (Simon, 1992: 82).

Equally important but perhaps far more significant is the lack of foreign exchange to sustain a policy of food imports. Not only has this compelled many sub-Saharan African countries to reduce food imports but it has also encouraged urban residents to produce their own food.

The economic decline in sub-Saharan Africa has also made ‘urban agriculture an alternative to cash payments for rising cost of food in the urban areas’ (Chimhowu and Gumbo, 1993:111). There is little doubt that urban agriculture is an essential survival strategy for many people. However, for many others, it is increasingly becoming a practical money saving activity. This occurs when, for example, successful urban farming releases money to fund the education of children. The apparent lack of official support for urban agriculture, in spite of its importance in the national economy and in the social lives of urban dwellers is, therefore, regrettable. It should be mentioned that there are some official concerns about urban agriculture. These are addressed in chapter 5.

1.2 Background of the Study

Farming in cities and towns is not a recent phenomenon. The focus of most studies of urban agriculture has been on crop rather than animal farming. Unfortunately, the author is a casualty of this syndrome. Thus, focus is on crop cultivation. Should the author have the opportunity in the future, he will study animal rearing by urban residents.

Most published books on urban agriculture were written by geographers, planners, political scientists, environmentalists, and so on. Consequently, their focus is different from mine. Most of them lay little emphasis on explaining why things happen. That is, they make several observations without explaining the reasons why. For example, many researchers have asserted that government officials in sub-Saharan Africa are increasingly condoning urban agriculture but they have not explained why this is so. As a sociologist, it is the author’s interest to find out why things happen or why things are what they are. As a result, this work is set apart from others.

Sociologically, the study of urban agriculture is important because, among other factors, it gives social scientists the opportunity to gather information on an important coping mechanism employed by urban dwellers. Similarly, through the study of urban agriculture, social scientists are able to know how people in need depend on their social networks for survival. In addition, by studying the characteristics of urban farmers in a particular town/city, one is able to know the least and best developed areas of that country. The study of the characteristics of urban farmers also makes it possible for social scientists to know who is more likely to engage in urban agriculture. In addition, knowledge gathered through the study of urban agriculture makes it possible for one to project the future supply of vegetables and other crops to urban areas.

In a small way, this study will indicate that when small-scale enterprises controlled by lower class citizens become very lucrative, middle/upper class citizens take control over them. Thus, due to their strong economic positions, the middle/upper class appropriates the innovations of the lower class.