![]()

1Phonemic and phonetic

Phoneme, allophone

When we talk about the sounds of a language, the term ‘sound’ can be interpreted in two rather different ways. In the first place, we can say that [p] and [b] are two different sounds in English, and we can illustrate this by showing how they contrast with each other to make a difference of meaning in a large number of pairs, such as

pit vs

bit,

rip vs

rib, etc. But on the other hand, if we listen carefully to the [k] of

key and compare it with the [k] of

car, or if we compare the vowel of

chew with the vowel of

coo, we can hear that the two sounds are not the same; the [k] of

key is more ‘fronted’ (‘palatalized’) in its articulation and has a higher pitch, while the [k] of

car is articulated further back and has a lower pitch. Similarly, the vowel [u] is fronted when it follows the palato-alveolar [tʃ], but retracted after the velar [k]. In each case we have two different ‘sounds’, one fronted and the other retracted. Yet it is clear that this sense of ‘sound’ differs from the first sense, for we could also say that fronted and retracted [k] are both variants of the one ‘sound’ k (and likewise, both forms of [u] are variants of the ‘same’ vowel). To avoid this ambiguity, the linguist uses two separate terms:

phoneme is used to mean ‘sound’ in the former (i.e. the contrastive) sense, and

allophone is used for sounds which are variants of a phoneme: sounds which differ, but which do not contrast. We would thus say that fronted [k] and retracted [k] are

allophones (i.e. variants) of the

phoneme k, and to make the distinction quite clear in writing, we enclose allophones in square brackets, [ ], and phonemes in slants, / /. Using this notation we can now write

(fronted k) and

(retracted k) as allophones of /k/.

Further examples of phonemes/allophones are readily available.

1 The [n] of

tenth differs from the [n] of

ten; in

tenth the sound is dental,

, while in

ten it is the ‘ordinary’ English alveolar [n] (compare the two sounds by looking into a mirror as you pronounce

them).

and [n] are allophones of the phoneme /n/; the dental allophone is found whenever another dental ([θ, ð]) immediately follows.

2 The [l] of lip differs, in many accents, from the [l] of pill. In pill, the [l] is accompanied by a raising of the back of the tongue: it is velarized. This sound, known as ‘dark l, and written [ł], differs from the ‘clear l’ of lip, usually written simply as [l]. These two sounds are allophones of the phoneme /l/. There is a corresponding difference of distribution: [l] occurs before a vowel, [ł] after one.

3 The [s] of

seep and the [s] of

soup are not identical. The phoneme /s/ has a plain, unrounded allophone, [s], in

seep, and a rounded, or

labialized, allophone

in

soup. As we might expect, the rounded allophone is used when a rounded vowel follows, and the unrounded allophone elsewhere.

Contrastive function

The native speaker

1* is quite readily aware of the phonemes of his language but much less aware of the allophones: it is possible, in fact, that he will not hear the difference between two allophones like and

even when a distinction is pointed out; a certain amount of ear-training may be needed. The reason is that the phonemes have an important function in the language: they differentiate words like

pit and

bit from each other, and to be able to hear and produce phonemic differences is part of what it means to be a competent speaker of the language. Allophones, on the other hand, have no such function: they usually occur in different positions in the word (i.e. in different

environments) and hence cannot contrast with each other, nor be used to make meaningful distinctions.

For example, as noted above [ł] (‘dark l’) occurs following a vowel as in pill, cold, school, but is not found before a vowel, whereas [l] (‘clear l) only occurs before a vowel, as in lip, late, like. These two sounds therefore cannot contrast with each other in the way that /l/ contrasts with /r/ in lip vs rip or lake vs rake; there are no pairs of words which differ only in that one has [l], the other [ł].

Predictability

The difference between phoneme and allophone can be seen in terms of predictability. Allophones are predictable in that we can say: in environment P we find allophone A; in environment Q, allophone B; in environment R, allophone C, etc. Thus, given the sequence -VI# or -VIC, where V stands for (any) vowel, C for (any) consonant, and # for word-boundary, we can predict that the allophone of /l/ occurring here will be [ł] and not [l].

Phonemic contrasts are not predictable in this way. Given the environment /–ip/, we have a choice between /p/ (peep) vs /l, w, s/, etc. From the phonetic environment there is no way of predicting which phoneme will occur. We shall see below that the predictability of the allophones can be expressed more formally by means of rules.

Most of the examples given so far have involved consonants. A well-known case of allophonic variation in vowels is the length difference, which is determined by the type of consonant following. Vowels are shorter in duration before voiceless consonants such as p, t, k, s, f, and longer before voiced sounds, such as b, d, g, z, v. The vowel of

lock is shorter than that of

log, and the vowel of

rice shorter than that of

rise. Using the length mark [

], we can show two allophones for each vowel: [ɒ, aı], short, and [ɩ

, aı

], long (for details of relative durations, cf. Umeda and Coker (1975: 552)). This example illustrates the points we made above; first, that the native speaker is not normally aware of allophonic differences (it requires careful listening to detect the difference between the shorter vowel of

lock and the longer vowel of

log), and second, that the allophones are predictable in terms of their phonetic environment: short before voiceless sounds, long before voiced ones.

Perception of allophones

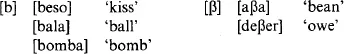

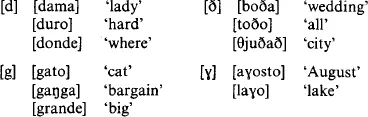

We are, as noted, not normally aware of allophonic variation in our own language; in listening to or learning another language, however, we may be able to perceive allophones which native speakers of that language are themselves unaware of, particularly if the allophones correspond to a phonemic distinction in our own language. An example is the relationship between voiced plosives ([b, d, g]) and voiced fricatives ([β, ð, ɣ]) in English and Spanish respectively. In Spanish there are three pairs of allophones, [b, β], [d, ð] and [g, ɣ], distributed as illustrated:

For a Spaniard, [b] and [β] are ‘the same sound’, as are [d] and [ð], [g] and [ɣ]; each pair are allophones of a single phoneme, the distribution being determined by the phonetic environment, namely:

plosives occur word-initially and after nasals (and laterals) fricatives occur between vowels (‘intervocalic’) and (for [ð] only) finally

The English speaker has little difficulty in distinguishing [d] and [ð] since the difference is phonemic in English: compare breathe and breed, riding and writhing. Similarly, [b, β] are readily distinguished, since although [β] is not an English sound, it is sufficiently similar to [v] to be heard as such; and /b, v/ is a phonemic distinction in English, like /d ð/. But [g, ɣ] are different; English has no /ɣ/, nor anything acoustically similar to it. In fact, [ɣ] is sometimes an allophone of /g/ in English: it is often found as a ‘reduced’ or casual pronunciation of /g/ between vowels, as in again, Agatha, eagle. Since [g, ɣ] are allophones in English as well as in Spanish, the perceptions of speakers in both languages tend to be similar: they are not normally aware of a difference.

In German, the ‘ch’ sound has two allophones; a velar fricative [x] after back vowels, and a palatal fricative [ç] after front vowels. English speakers are more aware of this difference than Germans, because they associate [x] with k-like sounds (i.e. with other velars), and [ç] with the acoustically similar [ʃ], which is a different phoneme. Germans perceive [x, ç] as ‘the same’ sound, since they constitute a single phoneme.

Often, therefore, we become aware of allophonic variation in our own language as a result of observations from speakers of other languages. Sapir, for example, found that his Haida (an American-Indian language) informants could readily distinguish the [th] of English top from the unaspirated [t] of stop, a difference noted only with difficulty by English speakers themselves. The reason is that, in Haida, [st–] contrasts phonemically with [sth–], i.e. the sound-difference is used to make differences of meaning. On the other hand these informants could hardly distinguish [t] from [d] (as in steer and dear), because Haida has no voiced–voiceless contrast (Sapir 1970 (1921): 55).

Similarly, Jones (1950: 37) reports the case of the spe...