![]()

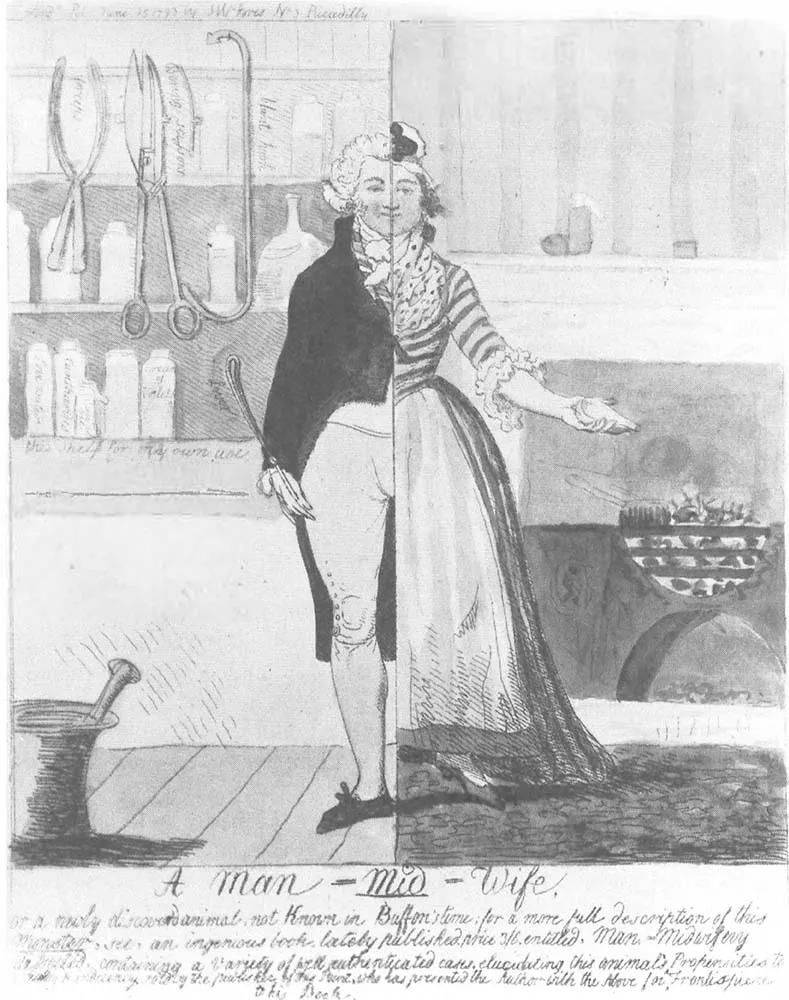

The puzzle of man-midwifery

In England in the seventeenth century, and doubtless for centuries before, childbirth was emphatically under the control of women. The midwife ran the birth, helped by several female “gossips”; men were excluded both from the delivery and from the subsequent month of lying-in. The enclosed female space of the “lying-in chamber” was dedicated to the mother’s rest and recovery and to the collective female ritual that surrounded childbirth. Medical men were only called upon to help in difficult deliveries and as a last resort; they had no place in the management of normal childbirth. This structure defined the horizons of both male knowledge and male ambitions in midwifery. Official medicine had no concept of the mechanism of birth, and knew very little of the anatomy of the uterus or the function of the placenta. Medical men might criticize the skills of mid-wives, but they had no ambition to replace them; and they accepted without comment the customary procedures of women such as the darkening of the lying-in chamber and the swaddling of the newborn child.

But in the eighteenth century there came into being a new kind of practitioner: the “man-midwife”, the man who acted in lieu of a midwife, the medical man who delivered normal births. These new practitioners at once created an explosion of knowledge, which has been called a “revolution in obstetrics”, and a series of institutional initiatives in midwifery.1 The works of Fielding Ould (1742), and especially of William Smellie (1752), opened the entirely new field of the accurate mechanical description of the processes of birth; and William Hunter, who in the 1760s succeeded Smellie as London’s leading man-midwife, produced the definitive description of the structure and function of the placenta in his great classic The anatomy of the gravid uterus (1774). While Hunter was engaged upon his 20-year study, midwifery institutions were proliferating, particularly in London. These included systematic teaching (led by Smellie, who taught over 900 male pupils in the 1740s), lying-in hospitals (four between 1749 and 1767) and lying-in charities (the first in 1757). Some of these developments found echoes in provincial cities, such as Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle; and the new male practitioners, taught by Smellie and his successors, swarmed through county and market towns from Devon to Yorkshire. Equipped with new knowledge, skills and aspirations, these men could now criticize the traditional female management of childbirth; thus the practices of women now came under attack, notably from Charles White in 1772. Correspondingly, the new man-midwifery was itself criticized — as immodest, interventionist, and a trespass on the work of midwives. Yet these polemics, which date from around 1750, had little effect. By the late eighteenth century men-midwives had achieved a permanent place in the management of childbirth, chiefly among the wealthy and urban sections of the population – that is, in the most lucrative spheres of practice. And as a result, the midwife’s position of trust and respect declined to the point where she could be stereotyped, in the 1840s, as “Sairey Gamp” in Dickens’s Martin Chuzzlewit.

How had this come about? Why did women desert the traditional midwife? How was it that a domain of female control and collective solidarity became instead a region of male medical practice? Why did a torrent of criticisms directed against “men-midwives” fall upon deaf ears? What was the relation between the new male knowledge and the new male practice? What had broken down the barrier that had formerly excluded the male practitioner from the management of birth? Was this a sudden development, or a gradual one; a matter of insidious growth, or a series of distinct steps? These are the questions that have animated this study; behind them lies a profound sense of puzzlement and surprise at the eighteenth-century transformation of midwifery from a female sphere to a central part of male medicine. The more one contemplates the achievements of the eighteenth-century men-midwives, the more one is struck by the contrasting female exclusiveness of the management of births in seventeenth-century England — and thus, the more surprising becomes the breaking down of that exclusiveness.

Such questions have particular interest today because in recent years the medical management of childbirth has come increasingly under attack. Advanced obstetrics, which has made childbirth vastly safer than ever before, finds itself in tension with modern feminism, which has given women the confidence to challenge the male control of obstetrics and to demand that childbirth be turned back from high technology to personal experience. By the 1980s the place, the personnel and the technical management of birth had all become matters of dispute, generating contests not only between different groups such as doctors, midwives and mothers, but also within a single profession as in the Wendy Savage case of 1983–84.2 All sides in such battles necessarily develop and deploy historical arguments as weapons of struggle. Thus childbirth acquires a history: a past that had been forgotten comes to light and loses its innocence.3 And in that history, the developments of the eighteenth century will have a central place for all protagonists – for it was between about 1720 and 1770 that childbirth became part of medicine.

There are two traditional explanations for the change: fashion and the forceps. Man-midwifery spread, it is alleged, by the process of fashion. At first adopted at the top of the social scale, it diffused downwards by a process of envious emulation — the “aping the quality” so much bemoaned and practised in Hanoverian England. Man-midwifery, on this argument, was rather like tea-drinking, the possession of coaches and livery servants, the taking of snuff, the wearing of wigs. But this explanation ignores the specificity of our theme; it forgets that there was a real alternative in the female midwife; above all, it begs the question as to how the process got started. What made man-midwifery fashionable in the first place? The alternative explanation is the midwifery forceps. Since its invention in the early seventeenth century, this instrument had been kept secret by its inventors and possessors, the successive generations of the Chamberlen family. But in the early eighteenth century, the forceps spread to other practitioners, and once its design was published in 1733–35, it was available for a few pounds from any competent instrument-maker. The release of the forceps appears to coincide with the rise of man-midwifery; the influential Smellie used and taught the instrument (and improved its design); it enabled the male practitioner to deliver a living child, where previously he could only deliver a dead one. On these grounds, the forceps has justifiably been seen as playing a crucial role in the rise of man-midwifery: as one scholar puts it, the forceps was “the key to the lying-in room”.4 Yet there are also good reasons to doubt this interpretation. As Margaret Versluysen has observed, the forceps was useful in only a tiny minority of deliveries; it was disliked by mothers; its misuse was “one of the main themes of the opponents of man-midwifery”; and it was even opposed by some of the leading men-midwives.5 Indeed, William Hunter himself declaimed against the forceps that “where they save one, they murder twenty … ‘tis a thousand pities that they were ever invented”.6 If this was the attitude of the acknowledged leader of the new man-midwifery, how can the forceps explain the rise of the man-midwife? The difficulties posed by these two explanations are underlined if we attempt to combine them. Fashion worked by downward social diffusion; yet forceps practice began among the poor, as indicated by the posthumously published Cases in midwifery (1734) of William Giffard, the first London forceps practitioner outside the Chamberlen family.7

Thus we have here an unexplained revolution, a massive social transformation with manifest effects but hidden causes. Moreover, both the timing and the location of this revolution were radically different from the analogous developments in medicine as a whole. Michel Foucault has taught us that it was in Revolutionary France, and specifically in the new Ecoles de Santé founded in 1794, that there occurred “the birth of the clinic”: the genesis of that “clinical gaze” that pierces the patient’s skin and literally sees the interior of the patient’s body as a living, dying presence in the consultation itself. Hence the invention of the physical examination, the active deployment of the technique of percussion, the creation of the stethoscope; the routine post-mortem, using death to dissect the tissues of the body; the entire system of pathological anatomy, and anatomical pathology, founded by Bichat and continuing (with important transformations) to our own day. Hence, perhaps above all, the depersonalization of the patient, the construction of that precise form of doctor-patient relationship in which the patient’s presence becomes a mere materiality.8 Simplified though Foucault’s picture may be, that picture certainly captured a real transformation in concepts, in ways of saying and seeing, and in the nature of medical practice. And in relation to this history, the medicalization of childbirth came too early, and occurred in the wrong country. Surely it was with Hunter’s practice that male medicine entered the lying-in chamber, just as it was with Hunter’s Anatomy of the gravid uterus that male medicine entered the womb itself Yet it was not in Revolutionary France, but in Hanoverian London, that these developments took place. Thus the transformation of childbirth from a female domain into a part of medicine cannot be assimilated to wider medical changes; it has its own, distinctive history.

Indeed, recent research suggests that the man-midwifery of eighteenth-century England was almost unique, apart from Britain’s American colonies.9 Elsewhere in Europe, although male practitioners acquired new skills, they were largely restricted to delivering difficult births until at least 1800.10 Moreover, the intervention of Enlightened governments brought into being a new cadre of skilled female midwives in this period. Concerned to enlarge the populations they governed, State and municipal authorities set about raising the standards of midwives’ practice by means of training systems, licensing schemes and sometimes the payment of salaries. The most systematic initiative of this kind took place in France, where between 1759 and 1783 the roving instructress Mme Le Boursier (later du Coudray), armed with Royal authorization, created a new kind of midwife — young, unmarried, and systematically-trained — throughout most of the kingdom: by the 1780s her pupils comprised two-thirds of the country’s mid-wives. Less ambitious schemes worked to similar effect, although on a more limited scale and chiefly within towns, in the Dutch Republic, in the German states, in the Italian cities and in Spain. Strikingly, all these efforts focused on the midwife rather than the male practitioner – because normal births remained in the hands of midwives. True, man-midwifery did develop to some extent in France: Andre Levret in Paris paralleled Smellie in London, and Mme du Coudray began to have male rivals in the 1770s. But elsewhere the midwife’s hegemony over normal births remained unchallenged. In Spain male practitioners were limited to delivering difficult births, and in the 1770s the midwife Luisa Rosado was even encroaching on this territory. In Italy, “throughout the [eighteenth] century, the presence of the man-midwife at a birth was rare”. In the Dutch Republic, “obstetric doctors were generally only present to assist in … obstetric emergencies” and made no attempt to take over from midwives. And in Germany, “the conflict between men and women midwives never developed”. The specificity of English developments shows that the rise of the man-midwife was by no means inevitable, and sharpens our explanatory puzzle.

Man-midwifery’s prehistory

A simple index of the eighteenth-century change is the publication of original midwifery treatises. From 1540, when Rösslin’s Rosegarten was translated into English as The birth of mankind, the popular demand for information about midwifery and related matters was met by translating into English the advice of one or many Continental authors.11 Before our period, almost nothing original on obstetrics had been published in English; the lead came from a distinguished French tradition – Paré, Guillemeau, Bourgeois, Mauriceau, Du Tertre, Portal, Dionis, Peu, La Motte – supplemented, after 1700, by the Dutch author Hendrik van Deventer. But all this changed dramatically from 1733, the year in which Edmund Chapman published his Essay towards the improvement of midwifery -the first account in print of the midwifery forceps. In the next decade (1733–42), seven authors (one a midwife, Sarah Stone, the others men) published original works on midwifery in English.12 From this point onwards, the original English midwifery treatise was the norm; the new publications attained a high standard of technical knowledge; and a continuous tradition connects the works of Chapman and his successors with the journal-literature in obstetrics of our own day. At the level of print, the “revolution in obstetrics” was very sudden: 1733 marks a permanent watershed.

Yet at least one seventeenth-century English medical man — Percival Willughby of Derby — had written original works on midwifery. His Observations in midwifery and The country midwife’s opusculum or vade-mecum, which remained unpublished in his lifetime...