![]()

Chapter 1

Bayesian Networks for Descriptive Analytics in Military Equipment Applications

David Aebischer

Contents

Introduction

DSEV

Frame the Problem

Ready the Experts

Pre-DSEV

Define

Structure

Elicit

Verify

Critical Decision Method (CDM)

References

Introduction

The lives of U.S. soldiers in combat depend on complex weapon systems and advanced technologies. Operational command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems provide soldiers the tools to conduct operations against the enemy and to maintain life-support. When equipment fails, lives are in danger; therefore, fast and accurate diagnosis and repair of equipment may mean the difference between life and death. But in combat conditions, the resources available to support maintenance of these systems are minimal. Following a critical system failure, technical support personnel may take days to arrive via helicopter or ground convoy, leaving soldiers and civilian experts exposed to battlefield risks. What is needed is a means to translate experiential knowledge and scientific theory—the collective knowledge base—into a fingertip-accessible, artificial intelligence application for soldiers. To meet this need, we suggest an operations research (OR) approach to codifying expert knowledge about Army equipment and applying that knowledge to troubleshooting equipment in combat situations. We infuse a classic knowledge-management spiral with OR techniques: from socializing advanced technical concepts and eliciting tacit knowledge, to encoding expert knowledge in Bayesian Belief Networks, to creating an intuitive, instructive, and learning interface, and finally, to a soldier internalizing a practical tool in daily work. We start development from this concept with counterfactuals: What would have happened differently had a soldier been able to repair a piece of critical equipment? Could the ability to have made a critical diagnosis and repair prevented an injury or death? The development process, then, takes on all the rigor of a scientific experiment and is developed assuming the most extreme combat conditions. It is assumed that our working model is in the hands of a soldier who is engaged with the enemy in extreme environmental conditions, with limited knowledge of, and experience with, the equipment that has failed, with limited tools, but with fellow soldiers depending on him (her) to take the necessary steps to bring their life-saving equipment back into operation and get the unit out of danger (Aebischer et al., 2017). The end product is a true expert system for soldiers. Such systems will improve readiness and availability of equipment while generating a sustainable cost-savings model through personnel and direct labor reductions. The system ensures fully functional operation in a disconnected environment, making it impervious to cyber-attack and security risks. But most importantly, these systems are a means to mitigate combat risk. Reducing requirements for technical support personnel reduces requirements for helicopter and ground-convoy movements, and this translates directly to reductions in combat casualties (Bilmes, 2013).

In On War, Carl Von Clausewitz wrote, “War is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty” (Kiesling, 2001). Clausewitz’s “Fog of War” metaphor is well-made and oft-used, becoming so popular as to become part of the modern military lexicon. Analysis of his writing has, naturally, led to discussion about how information technology can be brought to bear to reduce battlefield entropy. From this familiar territory, let us deliberately examine data analytics in context with combat uncertainty. Let us further refine that to the combat soldier and his equipment—in the most extreme scenario of enemy threat, geography, and environment—and determine what data analytics can put at a soldier’s fingertips. This task requires a fine balance of complexity and usability. It must be mathematically precise, yet infused with tacit knowledge. It must be exhaustive, as the consequences of failure can be dire. Most of all, the task must establish the primacy of soldiers at the point of need. We submit that this is a doable and necessary task and an opportunity to apply a unique analytics solution to this, and other, multivariate problems. This chapter will provide an introductory guide for tapping into an expert knowledge base and codifying that knowledge into a practical, useful, and user-friendly working model for diagnostics. In order, we will provide a general description of all the tools, techniques, and resources needed to construct the model, and then proceed through a practical example of model building.

The category of Descriptive Analytics, and diagnostics as a sub-category, serves well to frame our initial efforts. Korb and Nicholson (2011) describe:

By building artifacts which model our best understanding of how humans do things (which can be called descriptive artificial intelligence) and also building artifacts which model our best understanding of what is optimal in these activities (normative artificial intelligence), we can further our understanding of the nature of intelligence and also produce some very useful tools for science, government, and industry. (p. 21)

Causal analysis is at the heart of descriptive analytics. To perform this analysis, we will need a couple of tools: a knowledge engineering tool to capture knowledge about the domain of interest, and Bayesian networks to codify and represent that knowledge. The knowledge engineering tool and the Bayesian network tool work hand-in-hand, so they will be detailed as such. We will also need to designate a specific C4ISR system as a use case and as a practical example to demonstrate how each tool works separately and in combination with the other to model complex systems. For this, we will use the Army’s diesel engine-driven tactical generator, the primary source of power for Army Command Post operations. Generators meet our needs in terms of multi-domain complexity (electrical, electronics, and electro-mechanical) and in terms of ubiquity in combat environments. We will look at these tools individually in some detail, but we will focus more on how they overlap and how they integrate around our diesel generator use case. All of this goes toward learning how to work with limited or nonexistent data. Our richest source of knowledge is experts, and our actual data-generating process is from facilitating effective and efficient knowledge elicitation sessions with those experts. Our first tool will help us navigate the challenging, but rewarding, world of working with experts and expertise.

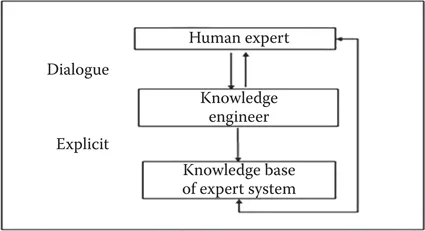

It is easy to recall instances where we have witnessed experts at work. The great artists—composers, painters, poets, musicians—seem to possess something that transcends talent, and they describe their art as something that occurs when their ideas have gone somewhere that was not intended. The process by which they create and do is not describable, existing only in their heads. It is much the same with equipment experts—possessing a blend of experiential and theoretical knowledge and an innate ability to apply that knowledge in ways few of us can comprehend. Coming to understand, and make explicit, even a fraction of this knowledge is the goal of knowledge engineering and the process of knowledge elicitation (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Knowledge engineering.

This process is painstaking, labor-intensive, and fraught with the danger of introducing many different biases, but the benefits of a well-constructed and executed knowledge elicitation make it worth the effort and outweigh the risks. It is in this process that we tease out the heuristic artifacts buried in the brains of experts. It is these artifacts that are carefully crafted into the artificial intelligence network that sits in a soldier’s hands.

The knowledge engineering process has its roots firmly in Cognitive Task Analysis (CTA). CTA involves a number of processes by which decision making, problem solving, memory, and judgment are all analyzed to determine how they are related in terms of understanding tasks that involve significant cognitive activity. For our purposes, CTA supports the analyses of how experts solve problems.

DSEV

Define, Structure, Verify, Elicit (DSEV) is a field-proven method for developing Bayesian models strictly from expert knowledge with a unique blend of soft and hard skills. DSEV is infused with techniques that mitigate bias and ensure the elicitation process aggregates expert judgments into a unified network. We will first outline the methods we use to execute each phase of the model and then, later, demonstrate how it is applicable, flexible, and scalable to a practical problem domain.

DSEV starts, stops, and cycles with experts. In both the theory and practice of Bayesian networks, assumptions—expert knowledge about any specific problem domain—are a necessary component. But it is inherently difficult for experts to explain what they know, and equally difficult for non-experts to understand what experts are saying. What is needed is a formalism for bridging the gap between experts and non-experts and codifying complex technical concepts into graphical structure and probability distributions. Our DSEV objective is an exhaustive prob...