- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Legal Aspects of Industrial Hygiene and Safety

About this book

The Legal Aspects of Industrial Hygiene and Safety explores various legal issues that are often encountered by Industrial Hygiene and Safety managers during their careers. A description is presented of the various legal concepts and processes that often arise in the IH/S practice, including tort, contract, and administrative law. The goal is to provide IH/S managers with sufficient knowledge to be able to incorporate legal risk analysis into everyday decision-making and policy development. This book will explore the legal issues that arise in IH/S practice and will be helpful to new IH/S managers as they progress in their careers.

FEATURES

- Explores various legal issues that are often encountered by Industrial Hygiene and Safety managers during their careers

- Provides insight into the legal issues and processes to IH/S managers that are traditionally only available to attorneys

- Improves the IH/S managers' ability to communicate complex IH/S issues to in-house counsel Presents tools and knowledge to IH/S managers so they can better consider the legal risks of the decisions they make

- Covers various legal concepts and processes that can arise in the IH/S practice, including tort, contract, and administrative law

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Legal Aspects of Industrial Hygiene and Safety by Kurt W. Dreger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Human Resource Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Employment Relationship

1.1 Introduction – Origins of Employment Law

Before delving into the law and the ways an IH/S professional may come into contact with the law, it is helpful to discuss the origins of employment law, and some of its key aspects. The vast majority of American workers are in some kind of employment relationship. The employer–employee relationship is one rooted in tradition and history and if healthy involves shared goals and expectations of both the employer and his employee. An employer, who wishes to earn profits by selling goods or performing services for customers, will quickly realize that he cannot sustain the volume of business needed to earn a profit without the aid of someone working on his behalf. He hires a person to help him carry out his business. So long as the employee is helping the employer create more income than the cost of the employee’s salary, the relationship, at least from the employer’s perspective, should flourish.

On the most fundamental level, the employee desires to earn a salary for his work to pay for food, shelter, and other life necessities. The employee is also motivated to work for benefits, such as health insurance, paid time off to focus on personal or family matters, paid sick leave, or retirement savings. Other motivating factors for an employee are career advancement, building a reputation in a career, or simply a feeling of self-worth for being a valued member of a profession. Compensation for work is very important, but it is often these other “soft factors” that lead to a feeling of job satisfaction.

1.2 History of Employment Law

Unfortunately, the above depiction of the employment relationship, where the employer is happily earning a profit and the employee experiences job satisfaction and employment stability, is not always the case. Conflicts between employers and employees can arise over a multitude of issues relating to denial of compensation or benefits, unsafe working conditions, discrimination, retaliation, performance issues, economic downturn, and a host of other things that can go wrong. Termination of employment is the ultimate end point to conflict between employers and employees. When termination is deemed unlawful, there might be legal action.

The body of law known as employment and labor law arose out of conflicts with the employment relationship. Before the advent of employment regulation, working conditions were often poor in the United States. Long hours, low wages, and unsafe working conditions ultimately lead to the passing of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (NLRA) and the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947 (LMRA), which govern the rights of workers in the private sector to create unions and engage in collective bargaining. Union employment rose steadily after the Great Depression and World War II. Union employment was highly organized and flourished in the blue-collar sector of the economy, including manufacturing, mining, and transportation.

In the last several decades, union employment in the United States has declined. There are many theories for why this is the case, including a negative public perception of the value of unions and the fact that labor-saving technologies continue to change blue-collar-type jobs. Nevertheless, union employment remains active in a certain sector of the economy. Musicians, actors, and professional athletes are highly unionized, as are college faculty members, engineers, physicians, and nurses.

Of interest to IH/S professionals is the collective bargaining process for health and safety controls. Often, the demand for greater worker health and safety protection is hotly contested in collective bargaining. In a particular accident investigation, the IH/S professional may find herself interacting not only with the supervisor and management, and the injured employee and any witnesses, but also with union representatives concerned with enforcing collective bargaining agreements.

1.3 Statutory Employment Regulation

If it is true that union employment is on the decline, the opposite may be said about Federal and state regulation of employment matters. Perhaps the most sweeping changes affecting the private employment relationship were the passage of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This Federal law, which was amended by Congress in 1972 as the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, made it unlawful for an employer to discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. As is often the case, states followed suit and created even more restrictive laws and regulations, protecting employees from not only adverse employment actions based on protected statuses as all of the above, but also public policy issues such as sexual orientation, genetic factors, or pregnancy.

Title VII, and the state laws that followed it, radically modified the traditional common law concept of “at-will” employment. At-will employment, the default employment relationship in virtually every state, provides that the employment relationship may be terminated by either party (i.e., the employer or the employee) for “any reason, or for no reason at all.” These federal and state laws transformed the traditional at-will employment relationship to one where an employee could be fired for any reason or no reason at all, but not for an unlawful reason, such as those that offend the public policy.

Since the passage of Title VII and the various pro-employee protections offered by the states, other protections relating to public policy considerations have emerged. Laws have been passed to protect employees from harassment and hostile work environments. When one thinks of harassment in the workplace, one usually considers sexual harassment, but laws are in place to protect employees from racial and national origin harassment too. Harassment claims not only involve employer liability, but they can also be brought against offending managers as an individual defendant. The legal standard for proving a prima facie case of harassment is fairly easy to meet, and employer liability is established by failure to respond to an employee’s complaint. Many companies have responded to the swell of harassment claims by providing required harassment training to management staff.

Following several high-profile cases involving shootings in the workplace in the 1990s, many states responded by passing workplace violence regulations. In California, workplace violence is treated like other hazards; employers must evaluate the potential for workplace violence, implement controls, and train employees.

Public policy has also driven legislative protections from disability discrimination and retaliation. These protections stem from the public position that no one should be fired because they suffered an injury (on or off the job) or have a medical condition that makes it challenging (but not impossible) to work or for doing the right thing by reporting unsafe conditions or illegal activities at work. Disability discrimination and retaliation have elements that come up frequently in IH/S practice. These concepts will be explored in much greater detail in Chapter 7.

1.4 Public v. Private Employment

Working for a government agency can be much different than working for a private company, at least in the employment law context. One major difference is that public employment is generally not “at will.”* In fact, public employment is often deemed a protected property interest by contract, implied practice, or statute. University professors, for example, often achieve tenure by operation of state law, or in the case of a private university by contract terms or collective bargaining agreements. No matter how a public job becomes a protected property interest, one thing is clear that a public employee has due process rights to her job.

Due process rights, as provided by the 5th amendment to the Constitution, and incumbent on state government by the 14th amendment, require a person to not lose his life, liberty, or property without a fair hearing. In the case of public employment, this usually means that termination may only occur after the employee has a fair chance to challenge the adverse employment action. The hearing must be impartial and fair. Thus, in the public sector, an employee intentionally committing an unsafe act can only be fired after a hearing and presentation of evidence.

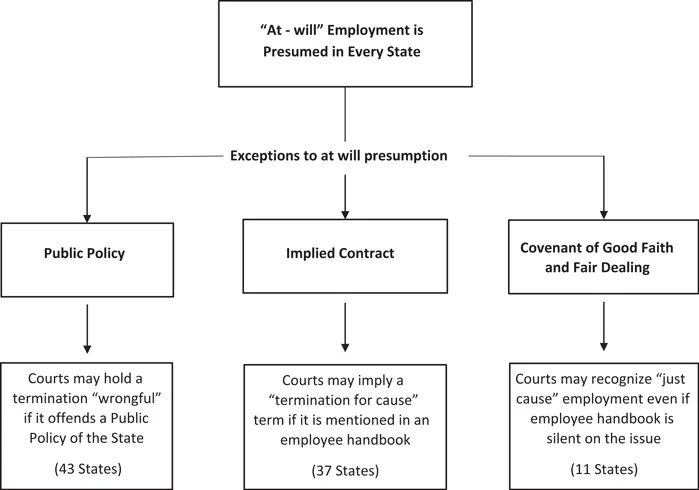

Private employment is not a protected property right in all jurisdictions. Thus, the default employment arrangement in the private sector is “at will.” However, several states have created exceptions to “at-will” employment in their legislative schemes. These include the public policy, the implied contract, and covenant of good faith and fair dealing exceptions.

We have already discussed the public policy exception in the context of discrimination and retaliation (see Chapter 7 for a more detail on these concepts). Under the public policy exception, one cannot be fired for reasons that offend the public policy,† such as:

- Refusing to commit an illegal act at the request of the employer

- Filing a worker’s compensation claim following an injury

- Calling the state occupational health and safety regulatory body to report an unsafe working condition

The implied contract exception involves basic concepts of contract law, which we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 3. Many employers publish employee handbooks or other documents that partially describe the terms and conditions of each job at the company. If such documentation mentions that employees have rights to appeal a termination or should be fired only for “just cause,” then courts will hold the employer to such statements even where the employment contract itself says the job is “at will.”

The final exception to “at-will” employment is the broadest and most protective of employees. It is recognized in a handful of states and is based on a fundamental legal principal that makes its way into all contracts – the terms of the contract must be fair and made in good faith to benefit both parties. The exception in essence says that when an employer and employee enter into an employment arrangement, the employee should always enjoy the right to be treated fairly. At the time of this writing, 11 states impute a good faith and fair dealing clause into every employment agreement, written or oral. This is not to say that private sector employees in these jurisdictions are entitled to a hearing or other due process before being fired, but rather the employer is obligated under the law to show just cause in every adverse employment situation. In essence, the bar to bring a wrongful termination lawsuit in these jurisdictions is low. As seen in Figure 1.1, “at-will” employment dominates in the United States, but powerful exceptions apply.

FIGURE 1.1 Legally recognized exceptions to “at-will” employment.

1.5 Agency Law

Employment law is rooted in agency law. Agency law arose out of two societal needs following the industrial revolution. First, as hinted at in the opening paragraphs of this chapter, business owners needed others (i.e., employees or agents) to help them carry out the business. Without such help, a business owner would be compelled to carry out all functions of the business, which is obviously not feasible in an expanding industrial enterprise. Second, as a business grows, it interfaces with customers, regulators, and members of the public. Sometimes, mistakes are made and customers can be harmed by the wrongdoings of the business. If a harmed individual were limited to suing only the person who actually caused the harm (e.g., an employee), then she would be denied a recovery from the true beneficiary of the business – its owner or principal.

Agency law was devised, in part, by the courts to set the ground rules for when an employer is liable for harms (financial or physical or emotional injury) caused by his employees, and when it is not. It also regulates the circumstances under which an employer (i.e., principal) grants authority to his employee (i.e., agent) to carry out the objectives of the business. Authority vested in an employee is typically express, but often is implied through past conduct of the principal. Apparent authority (e.g., neither expressed nor implied) to act on behalf of the principal may be found where circumstances suggest a third party reasonably relied on assurances of the principal’s agent.

The following case illustrates these points, particularly the authority that is created in an employment relationship, and in the context of workplace injury. This case may ring a lot of bells for IH/S practitioners, especially ones experienced in workers’ compensation determinations.

1.6 Mill Street Church of Christ v. Hogan (785 S.W.2d 263 Ky. (1990))

1.6.1 Facts

Mill Street Church of Christ and State Automobile Mutual Insurance Company petitioned for review of a decision of the New Workers’ Compensation Board [hereinafter “New Board”], which had reversed an earlier decision by the Old Workers’ Compensation Board [hereinafter “Old Board”]. The Old Board had ruled that Samuel J. Hogan was not an employee of the Mill Street Church of Christ and was not entitled to any workers’ compensation benefits. The new Board reversed and ruled that Samuel Hogan was an employee of the church.

In 1986, the Elders of the Mill Street Church of Christ decided to hire church member, Bill Hogan, to paint the church building. The Elders decided that another church member, Gary Petty, would be hired to assist if any assistance was needed. In the past, the church had hired Bill Hogan for similar jobs, and he had been allowed to hire his brother, Sam Hogan, the respondent, as a helper. Sam Hogan had earlier been a member of the church, but was no longer a member.

Dr. David Waggoner, an Elder of the church, soon contacted Bill Hogan, and he accepted the job and began work. Apparently, Waggoner made no mention to Bill Hogan of hiring a helper at that time. Bill Hogan painted the church by himself until he reached the baptistery portion of the church. This was a very high, difficult portion of the church to paint, and he decided that he needed help. After Bill Hogan had reached this point in his work, he discussed the matter of a helper with Dr. Waggoner at his office. According to both Dr. Waggoner and Hogan, they discussed the possibility of hiring Gary Petty to help Hogan. None of the evidence indicates that Hogan was told that he had to hire Petty. In fact, Dr. Waggoner apparently told Hogan that Petty was difficult to reach. That was basically all the discussion that these two individuals had concerning hiring a helper. None of the other Elders discussed the matter with Bill Hogan.

On December 14, 1986, Bill Hogan approached his brother, Sam, about helping him complete the job. Bill Hogan told Sam the details of the job, including the pay, and Sam accepted the job. On December 15, 1986, Sam began working. A half hour after he began, he climbed the ladder to paint a ceiling corner, and a leg of the ladder broke. Sam fell on the floor and broke his left arm. Sam was taken to the Grayson County Hospital Emergency Room, where he was treated. He later was under the care of Dr. James Klinert, a surgeon in Louisville. The church Elders did not know that Bill Hogan had approached Sam Hogan to work as a helper until after the accident occurred.

After the accident, Bill Hogan reported the accident and resulting ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Author

- Chapter 1 The Employment Relationship

- Chapter 2 Multi-employer Worksite Regulations

- Chapter 3 Contract Law

- Chapter 4 Tort Law

- Chapter 5 Administrative Law

- Chapter 6 Criminal Law

- Chapter 7 Workplace Discrimination and Retaliation

- Chapter 8 Workers’ Compensation

- Chapter 9 Evidence Law Topics

- Chapter 10 Influencing IH/S Organizational Policy and Compliance Strategy

- Index