- 100 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cathodic Protection for Reinforced Concrete Structures

About this book

Cathodic protection of reinforced concrete structures is a technique for rescuing corrosion damaged structures and, in certain instances, preventing them from corroding in the first place, and its use is growing.

This book is for specialist contractors, large consultants and owners of corrosion damaged structures, and looks at international experience with this technique. It examines why corrosion is occurring, the differences in the application of CP with the stark dichotomy in its success and failure, and finally ways in which its performance can be improved on future installations. Information is valuable, as the success or failure of the CP system has a marked effect on the service life of the structure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cathodic Protection for Reinforced Concrete Structures by Paul M. Chess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Corrosion Process in Reinforced Concrete

The State of the Art

INTRODUCTION

The use of steel in concrete has increased massively in the last century, and it is now one of the most commonly used building materials on earth (second to water in usage by mankind). The biggest durability problem with structures of this material is corrosion of the steel reinforcement. The cause of this corrosion that is most difficult to remedy is the presence of chloride in the concrete, which allows the steel to corrode at a rapid rate. Because of the huge economic significance of this problem over the last 50 years, there has been almost continuous research in many countries to categorise the problem.

There have been significant attempts to improve the actual life of a reinforced concrete structure by changing the material properties of both the reinforcement and concrete. Secondly, there have been changes to cover depths of the concrete. Relatively recently, certain countries, such as Saudi Arabia, have been installing cathodic prevention on a large scale to prevent corrosion from initiating by forcing the steel reinforcement to remain as a cathode.

As of yet, there has not been a thorough look at changing the structural design of the steel reinforcement in order to minimise the risk of premature corrosion, although this practice has been ongoing for many years in the case of steel structures. This design change would be to minimise the formation of anodic sites where preferential corrosion occurs.

The aim of this chapter is not to repeat the accepted wisdom of previous textbooks but to look at the results of recent research and contemplate an alternative view of the corrosion process.

THE CORROSION PROCESS

How steel corrodes in concrete is of significant importance when trying to understand the likely mechanisms and possible rates. If a clean-surfaced, grit-blasted, rebar is put in a saline, pH-neutral solution, then there will be a rapid browning over the whole surface area. A bright yellowish brown oxide will form within minutes and gradually become darker as the exposure time increases. This is commonly referred to as microcell corrosion, as it is appearing evenly over the whole surface of the rebar. As the exposure time increases, the rate of corrosion reduces, as the oxide layer provides a barrier to ionic, atomic and gaseous transport.

In reinforced concrete structures, when the contaminated concrete cover is removed after many years, the corrosion process is not so simple. There can be areas where corrosion appears to be general with uniform section loss (refer to Figure 1.1). This tends to be in areas with lower cover depth and relatively dry carbonated concrete.

FIGURE 1.1 Example of significant general (uniform) corrosion on a marine structure.

There can also be corrosion pitting where there is a significant loss of section at defined locations (refer to Figure 1.2 and, for the result of this loss of section, to Figure 1.3). This is most commonly found in wet and high-cover parts of a structure. When exposed, the oxides found in these pits often have some black and green colourations and can smell of chlorine gas or hypochlorous acid, both recognisable from swimming pools. In this case, the oxidation product does not appear to provide a protective barrier and indeed may be providing a poultice where low pH and aggressive ions can remain (Figure 1.4).

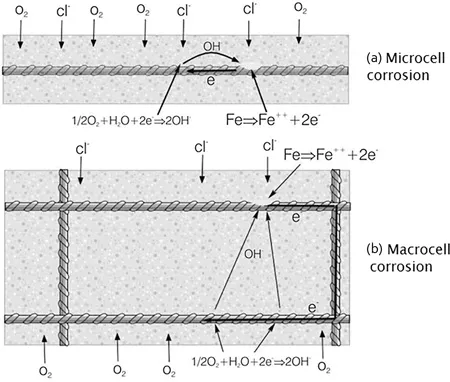

FIGURE 1.2 Schematic of micro- and macro-corrosion mechanism.

FIGURE 1.3 Corrosion of reinforcing steel causing failure of a waffle deck in August 2017.

FIGURE 1.4 Corroded steel reinforcement showing pitting corroded steel.

So it appears that there are at least two distinct corrosion mechanisms as shown schematically in Figure 1.2. Several researchers (Green, 2017) have looked at different hypotheses for pit formation, and presently, the most favoured is the transitory complex model where the chloride ions form a soluble compound, which moves away from the anodic site at the base of the pit. Away from the corrosion site, the iron hydroxide precipitates re-releasing the chloride ions. This mechanism has been observed (Angst et al., 2011) on actual reinforced concrete specimens with initial pit formation and the corrosion product deposited on the rebar a small distance away. It seems likely that there are several stages to pit formation and the actual mechanisms will be varying through the corrosion process. What the above findings demonstrate is that the corrosion process is much more complex than that in a solution and thus cannot be modelled using the standard electrolytic formulas such as the Stern Geary equation. This is an equation that relates quantitatively the slope of a polarisation curve in the vicinity of the natural corrosion potential to the corrosion current density and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Another variable that has only recently started to be explored is the differences in the composition and structure of the reinforcement itself having a significant effect on corrosion initiation and propagation. For example, it has been found that manganese sulphide inclusions can preferentially be corroded in chloride-rich reinforced concrete, and this could initiate or fully form pits. Other observations which have been made are that the form of hot roll processing favouring, respectively, pearlite and lower- or upper bainite also has a significant influence on the form and extent of the corrosion process. Recently, the entire steel–concrete interface has been looked at more closely and a review published (Geiker, 2017).

The initial iron oxidation reaction is anodic and involves the loss of electrons, which can be represented by

This initial reaction is then followed by several further reactions leading to a more ionically charged atom and further electron production. The important point is that there are electrons being produced and that these are travelling through the steel matrix to the cathode on the steel surface, which is a non-corroding area where they combine with oxygen and water in the cathodic reduction reaction. In the microcell-type corrosion, this is likely to be with the anode and cathode as part of the same grain, which is typically from 0.25 mm down to 0.025 mm. This is because steel is an alloy with components that have different potentials.

THE AMOUNT OF CHLORIDE REQUIRED TO INITIATE CORROSION

This has been exhaustively evaluated over many years, and a review of the many experimental procedures undertaken was published (Angst, 2009). In this review, the parameters that affect the onset and amount of corrosion are discussed and found to include:

- Steel–concrete interface

- Concentration of hydroxide ions in the pore solution (pH)

- Electrode potential of the steel

- Binder type

- Surface composition of the steel

- Moisture content of the concrete

- Oxygen availability at the steel surface

- Water-to-binder ratio

- Electrical resistivity of the concrete

- Degree of hydration

- Chemical composition of the steel

- Temperature

- Chloride source

- Type of cation accompanying the chloride ion

- Presence of other, inhibiting or otherwise, species

With all these variables, it is perhaps not surprising that there would be a significant range in the critical chloride level. However, what was not anticipated was the huge range in chloride levels where corrosion has been initiated in different research studies, and these ranged from 0.04% to 8.4% chloride by weight of cement, which is a 21,000% difference (Angst, 2009). This massive difference is to a certain extent replicated in real structures where the range was from 0.1% to 1.95% chloride by weight of cement, which is a 1,950% difference. These huge disparities mean that deterministic life expectancy modelling, which is applied to many important and vulnerable structures and has been refined and honed over many years, is inherently flawed. This is because all these models take an arbitrary chloride level and assume that the chloride will move through the concrete at a certain diffusion rate following Fick’s law until it builds to a sufficient concentration level when it depassivates the steel reinforcement. If the level of chloride required to initiate corrosion is extremely variable, then this model cannot be followed with confidence. A more effective method may be to move to a probability distribution for the threshold. Later in this chapter, the assumption that a diffusion model is the way that charged ions move around a structure is also looked at more closely.

THE EFFECT OF THE STRUCTURE’S SHAPE ON CORROSION

Recently, an experiment was undertaken (Angst and Elsener 2017) where the specimen size was varied in the same experimental procedure. It was found with exactly the same experimental conditions and procedures that reinforced concrete samples with 1 cm, 10 cm and 100 cm lengths required very different chloride concentrations to initiate corrosion. No corrosion was found at more than 2.4% chloride by weight of cement for the 1 cm sample, with the 10 cm sample initiating corrosion at an average of 1.5% chloride by weight of cement, and the 100 cm sample initiating corrosion at an average of 0.9% chloride by weight of cement.

This has profound implications in that it means that the steel reinforcement layout has a large effect on the results obtained both in experimental procedures and also more importantly in real structures. Even more worryingly, these large real structures are likely to perform substantially worse than may be predicted by laboratory testing with small samples. The reason for this behaviour was conjectured by Angst and Elsener (2017) to be that the bigger the area of the steel reinforcement, the more likely there was to be inhomogeneities on the surface of the steel where this corrosion process can prosper. Whatever the reason for the results, this experiment shows that the presence and layout of steel in the concrete has a dramatic effect on the corrosion process, and this should be considered important. Most of the durability experiments that have been undertaken to date have neglected this fact. With this experiment and some further evidence which is outlined below, it should be understood that concrete on its own and steel reinforced concrete do not necessarily behave in the same way.

IONIC MOVEMENT IN CONCRETE

Modern structures in aggressive environments are increasingly being engineered to achieve a life expectancy based on the impenetrability of the concrete to chloride ions. These predictions are normally based on Fick’s laws of diffusion even though it is commonly known that this is an over simplification of the transport situation in concrete. It is widely known that advection (capillary suction) and migration can occur in concrete, and its common use is probably linked to its simplicity and ability with certain situations to adequately predict reality with adequate precision. Fick’s law is a concentration diffusion mechanism and assumes that transport is occurring in concrete in exactly the same way as in an aqueous bath. This is probably a reasonable assumption for a simple concrete sample, but it is not so reasonable when there are electrical potential differences in the structure, such as between two steel bars in a reinforced concrete sample and the huge number of bars at different depths and orientations in a real structure. The effects of this difference in potential will be to create an electrical field that promotes the movement of ions by electro-osmotic flow from the anode to the cathode or vice versa depending on their charge and so...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Author

- Chapter 1 The Corrosion Process in Reinforced Concrete: The State of the Art

- Chapter 2 History of Cathodic Protection in Reinforced Concrete

- Chapter 3 Present Use of Impressed Current Cathodic Protection in Reinforced Concrete

- Chapter 4 Present Use of Galvanic Anodes for Cathodic Protection in Reinforced Concrete

- Chapter 5 Future Use of Cathodic Protection in Reinforced Concrete

- Chapter 6 How Cathodic Protection Works in Reinforced Concrete

- Chapter 7 Defects with Existing Standards

- Index