![]()

1 Introduction

The history of transplantation is, above all, a story of mythology, human fantasy, and innovation. Attempts at transplantation had been made for hundreds of years but typically resulted in death. The modern beginning of transplantation is the successful transfusion of blood. By the turn of the century, differences in human blood groups had been discovered, greatly reducing the risks of transfusions. Various attempts at solid organ transplantation were made in the first half of the century: a human kidney in Kiev in 1933, without success, and later at other medical centres in the 1940s and early 1950s, without greater success (although the physicians involved typically considered a "success" any survival for few hours or for a few days).

In 1954 Joseph E. Murray and associates successfully transplanted a kidney from one identical twin to another. During the remainder of the 1950s and throughout the 1960s, kidney transplantation increased in frequency. Organs came either from living relatives or non-heart-beating cadavers: however the cadaver kidney results were initially not as successful as those from genetically related living donors. Subsequently, not only kidney but heart transplantation (the first carried out by Christiaan Barnard in 1967) as well as other types of transplantation accelerated, particularly as knowledge about immunological defence mechanisms and ways of countering or neutralising them were developed.

Organ transplantation is today a well-established clinical treatment and part of the specialised surgical services in many hospitals in the world. The rate of successful organ replacements is quite high, particularly for kidneys, but also for the replacement of hearts, whole or parts of pancreas and livers. Today, a major development is ongoing experiments with animal grafts and genetic manipulation of animals to make their organs more compatible with human recipients.

Housing Organ Transplantation’s Social Impact

Already from its outset, organ transplantation surgery was a dramatic offspring of modern heroic medicine. It promised to be a surgical panacea that would extend the life of many chronically ill and end-stage patients.

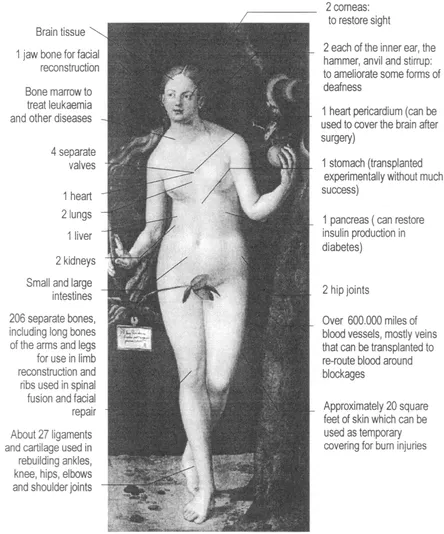

Figure 1. Usable organs and tissue from a single corpse

In more than one sense organ transplantation suited popular visions of a science that in a foreseeable future would make it possible to establish human colonies on the moon and to extend human life almost indefinitely.

The expansion and development of organ transplantation as regular procedures in health care services has had an impact beyond the clinic. It has affected the legal, organisational and cultural conditions for the access, use and transfer of body parts for therapeutic and research purposes. In particular, the demand for biological tissue and organs in health care services makes the attitudes and conceptions of people regarding the disposal of their own remains and their next of kin's bodies after death – otherwise a private or family affair – a matter of health care policies and legislation. These concerns are of critical importance in how transplantation systems operate and are understood and accepted by the people participating in or affected by them. In this regard the implementation of this biotechnology – and related policy and legal formulations – is consequential for social understandings about bodies, death and giving, or the relation between a person's rights and the collective rights with respect to her body and its parts.

An unintended consequence of these developments has been the revival of philosophical and ethical issues concerning the body, consciousness, existence and identity in the context of contemporary high technology medicine. Along these lines, Featherstone et al. (1991) points out, the impact of scientific high technology in medicine has raised difficult philosophical and ethical problems: for example, who ultimately has legal ownership of parts of human bodies? What is the role of the state in protecting the patients from unwarranted or unethical medical action? What are the professional and sociocultural risks of organ transplantation over the long run?

Symbolically, the process of organ transfer as such conveys a powerful metaphor. The process that takes place in a transplantation is a true metamorphosis – the transformation of a deceased's body part into a suitable biomedical implant – where the meaning of a body part gets redefined along the way. This transformation from deceased somebody into graft organ implies the crossing of many boundaries, not only physiological, but also cultural, legal and ethical ones. Such transgression of borders in many senses of the term is noted by Braun and Joerges (1993:1):

The building up and the dynamics of European and the transborder organ transplant systems can hardly be understood without taking into account the blurring of categories between body and machine, between gift and commodity, between individual and collective ownership, between moral duty and abomination, between life and death.

The organisation and management of this alchemy of transforming the dead into "living" organs is institutionalised in an organ transplantation system. This process configures an axis of polarities, a social process, stretching between a braindead donor at one extreme and an organ receiver at the other. This process is characterised by particular social definitions and social rule systems associated with such socially defined states as "alive", "braindead", "patient", "organ donor" etc. The social rules applying to the different states indicate what is the correct and appropriate treatment towards a person in one or another state, whether a dead person or a living patient with different degree of life or living. A "deceased" is not the same as a "cadaver" because while the first term implies a set of social relations denoting a former person – an identifiable dead someone who has been part of a social relations network – the second term denotes an object with medical or biological connotations rather than social aspects. The deceased suggests a dead person, but still a person who has been part of a sociocultural context. The deceased still has a name, relatives, testament, property. The corpse as a dead body has already lost most of its social and subjective aspects. It is a decontextualised body, an object in a certain sense, (for which the notion of human agency is completely absent). While the body of a deceased is only a remains but still a sacred one, the cadaver is not, and, as such, this term is used for humans as well as animals, implying that the disconnection with human society is complete, thus becoming a part of the "natural world".1

Clearly, the use of human biological material has enormous potential due to the possibilities it opens for the cure of several debilitating and end-stage diseases (see figure 1). A transplant industry based upon foetal-tissue technology promises to dwarf the present level of organ transplantation. According to a US estimate, "foetal cell implants have the potential to offer relief to several million Americans, including one million with Parkinson's disease, 2.5 million to three million suffering from Alzheimer's disease, 25000 with Huntington's disease, 400,000 stroke victims, 5.8 million diabetics, and several hundred thousand people with spinal cord injuries" (Thome, 1987). The prospect of a technical-medical development based on massive utilisation of human biological material does not belong to science fiction any longer.

Solid organ transplantation (heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, pancreas) offers the most dramatic life-saving dimension, and the greatest publicity to transplantation practice. It promotes the idea that the medical profession can through heroic measures overcome death and prolong life. Human tissue transplants are for the most part life-enhancing rather than life saving, but solid organ transplants are more dramatic and newsworthy than life-enhancing tissue implants. Organ and tissue transplantation, linked closely to the use of high technology and science, has come to be regarded by much of the public as epitomising the advancement and development of society – there is an aura of excitement, a wonderment associated with the transplantation of solid organs (O'Neill, 1996:5-6).

The Sociology of Organ Transplantation

How can sociology be applied to the study, and contribute to the understanding, of transplantation processes and systems? An organ transplantation system (hereafter OTS) can be systematically investigated in terms of, among other things, its complex social organisation, its legal and administrative aspects, the involvement of multiple professions, and the management of organ exchange in national and international networks. The OTS is characterised by precise coordination and tight coupling of many types of actors and activities using complex sophisticated technologies. The social processes, organisational and professional features, legal and cultural aspects of the OTS are among the possible important topics for sociological research. The impact of such technological development on social life is another potential area of sociological research. Cultural factors are also worthy of study in that they shape the ways in which people view and react to transplantation – not least the use of human body parts – and affect its operation and development. A number of interesting research questions can be imagined in any broad consideration of organ transplantation. This can be done with different approaches or perspectives depending on the interests of the researcher.

As of today, there are few sociological studies of organ transplantation. In the USA, Renée Fox and Roberta Simmons with her associates are undoubtedly the leading sociologists working in this field. Fox's research has a strong cultural orientation that can be characterised as a "thick" analytic and interpretative description of important themes in the sociology of medicine and therapeutic innovation: the medical profession, human experimentation, medical technology, dialysis and transplantation. It concerns the cluster of surgical, medical and technological means for treating certain end-stage diseases that occupy a central and consistent place within medicine and the public imagination (Fox, 1959; 1988; 1989, etc.). The Courage to Fail (Fox and Sweazy, 1974) is one of the pioneering sociological studies in research on transplantation and dialysis. Over a period of four years, the authors collected data through field research (participant observation, face-to-face interviews, analysis of documents, etc.) in transplant and dialysis centres located in several regions of the USA. Their work presents a broad tapestry of the dilemmas and ambivalence associated with clinical medical research, and also attends to the impact that kidney transplantation has had on physicians as well as recipients, donors and their families.

For example, the development of new technologies such as heart and kidney transplantation and dialysis created for the physicians involved new types of decision problems and new ethical dilemmas. There were no established norms and guidelines to direct them, to help them make difficult moral choices, for instance, in determining who should get access to the scarce life-giving techniques. Over time, physicians developed new criteria for making difficult life-and-death decisions. These technological developments have not been unproblematic or an unmitigated good. One of Fox's major ideas (Fox, 1984) is that the development of modern medical technologies not only creates new types of dilemmas and types of decision problems, but has brought forth circumstances where the institutionalised strategies of "save-life-at-all costs" and "aggressive intervention" are considered less and less appropriate. Fox sees a contemporary trend toward a new medical approach oriented less to the sanctity of life and "save-life-at-all-costs" and more to the "quality of life". This is reflected in professional and popular movements for "death with dignity", and "the right to die". This trend reflects, in her view, a major shift in cultural assumptions about health and illness in the USA (see also Anspach, 1993:41).2

In Europe, Bernward Joerges and his group at the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin have studied organ transplantation from the perspective of large-scale technical systems with networked operations that are not only technical but non-technical in character. (Joerges, 1988; Joerges and Braun, 1990).3 Such a system consists of a variety of different parts or subsystems: organisational, professional, technical units, hospitals and transplantation centres in different countries. It entails a highly complex organisation. Their approach examines, in part, the interlining features of complex, technical systems and, in part, the boundaries and limits between a large-scale technical system such as organ transplantation and its environment.4

One aspect of "large-scale" is the high dispersion, both temporally and spatially (specifically, transborder or international), and the interdependent technical heterogeneity. Such systems link a wide spectrum of varied technologies and occupational and professional groups – not only medical but also non-medical. Joerges and his colleagues stress that because organ transplantation systems are, both spatially and functionally, widely dispersed, they require a high degree of standardisation and compatibilisation of the organisation, the communication systems, and exchange relationships. Systems such as OTS – they also refer to hazardous waste disposal – are considered "infrastructural service systems". They are science-intensive but also highly dependent on public acceptance and legitimisation.

Transplantation has not simply been a surgical technique. It is closely associated with the expansion of immunological and genetic research (Braun, 1994). In contrast to many other large technical systems, "affected parties" play an important role, that is recipients and their relatives, as well as donors on whom the system is greatly dependent for a strategic resource (Braun, 1994:11). The functioning of transplantation systems is constrained by the scarcity of organs, and there has been a growing gap between transplant demand and supply. For instance, in Germany, as elsewhere, the number of grafts obtained has grown continually over the past twenty years but the chance of a person on a waiting list receiving a transplant has dropped in relative terms (Braun, 1994:15). Braun correctly points out that the supply of organs for transplantation depends primarily on the medical definition of death, the number of actual deaths fitting the definition, the commitment of physicians to organ transplantation surgery, and the willingness of the population to donate organs or to support legislation providing ready access. Also, as with other current medical biotechniques, it is to a large extent embedded in the higher-level organisation of medical services, but its functioning depends on broader infrastructural, structural and "transborder" conditions (Braun and Joerges, 1993).

The organisation of organ transplantation systems OTS is not only a large scale system (Joerges, 1993) but entails tightly-coupled processes of organ harvesting, organ extraction, and organ implantation as well as recipient follow-up (Cabrer et al., 1992).5 The nature of the technical components and the mode of their integration with social components in given organisations has a decisive influence on an OTS's performance and system dynamics. In this perspective, technologies, or more generally technical artefacts, are not merely potential determinants of social relations, not merely potential products of socially regulated human activity (Winner, 1977:14). Rather, they are integral components of social systems, and as such can be objects of sociological analysis (Mayntz, 1989).6 The sociotechnical character of OTS entails the interaction of several medical professions, and advanced medical skills and technology – such as standardised surgical techniques, appropriate equipment (for example dialysis or heart-lung machines), permanent access to support facilities (such as operation theatres, intensive care units and typing laboratories to analyse the suitability of the organs and organ-recipient matching), pharmaceuticals (essential to immunosuppression, and organ preservation).

Moreover – as in few other medical fields – organ transplantation routines are highly dependent on extra-medical technical infrastructure, in particular communication and transportation networks (mainly by road and air). This infrastructure, ranging from energy and water supply, national communication networks etc. is simply utilised by OTS agents. However, the functioning of the OTS is highly dependent of the operation and quality of these systems. Braun and Joerges (1993:14) stress the importance of the extra-medical infrastructure:

When due to a software error, the AT&T (telephone) network broke down in 1990, transplantation activities largely came to a halt in the US. Participating hospitals could no longer be co-ordinated, and it became impossible to locate relatives of deceased patients for obtaining organ donations.

Infrastructural conditions act as constraints on, and supports to, the functioning of organ transplantation systems. Even apparently marginal phenomena such as traffic accidents play a role in organ supply. In many countries, victims of accidents (particularly motorcycle accidents) with their characteristic head traumas, are an important source of organ donors (these are relatively young, healthy sources). Geographical factors such as the size of an organ harvesting region coupled to the transportation and communications available to the local transplantation centre, tend to affect the pattern of, for example, a heart transplantation (the optimal preservation time of a graft heart should not exceed four hours; this problem does not particularly affect geographically small European countries, but in a geographically dispersed country such as Sweden, the time needed to fly the length of the country at 800 km/h is 2.37 hours, to which must be added other moments in the transportation process not considered in the calculation; this leaves a short time marginal for implantation).

Problems with the technical infrastructural support in less industrialised countries seriously constrain effective organ transplantation. For example in India, organ transplantations are largely accomplished with living donors, since the supply of cadaveric organ donors is very low due to inadequate organisational and technical infrastructures (Slapak, 1987:18). More generally, some countries adopt these techniques without the necessary legal and cultural preparatory measures to support, for example, a "culturally accepted and politically safeguarded donor system", with the result that these countries depend on international organ supply (Braun and Joerges, 1993:26).

Another important characteristic of the OTS is, as mentioned earlier, its "transborder" character. Locally based organ transplantation organisations today are participants in a transborder organ transplantation system (Braun and Joerges, 1993). The transborder requirements of OTS means that the various health care systems participating harmonise not only technically, but also pr...