eBook - ePub

Neutrality and Foreign Military Sales

Military Production and Sales Restrictions in Austria, Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland

- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Neutrality and Foreign Military Sales

Military Production and Sales Restrictions in Austria, Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland

About this book

This book compares the foreign military sales policies of the four European non-aligned countries—Austria, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland—using public opinion as an explanatory factor. These non-aligned states have accepted a policy of 'armed neutrality'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Neutrality and Foreign Military Sales by Björn Hagelin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Military Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Is there anything peculiar about neutrality apart from formal non-alignment in peacetime and the attempt to stay neutral in wartime? If so, what is it? These questions are as old as they are controversial (for reasons of simplicity the terms non-alignment and neutrality are used as synonymus in describing the general peacetime policy). On the one hand governments of neutral countries argue that neutrality is a peace-supporting and stabilizing policy in a world dominated by major-power politics. Representatives of alliance members, on the other hand, are not late to respond that ‘peace’, meaning primarily the avoidance of a ‘hot’ East-West war in Europe after 1945, is the result of the two super-power alliances and their deterrent effects. From this point of view nuclear weapons and their ‘mutually assured destruction’ have secured peace through fear. In such a bipolar view of the world, neutrality may even be regarded as a destabilizing policy.

There is also the argument that neutrality as such is not a viable alternative in a future war in Europe. The reason is not only that a future war is assumed by many to be, or to quickly become, an all-out nuclear conflict with no survivors. The reason is also that the neutrals in Europe, all of them small countries, are not seen by the critics to pursue a strictly neutral policy. Instead, because of the strong dependence of the neutrals upon international trade in general, and upon trade with the Western industrialized countries in particular, their foreign and security policies are also assumed to be biased. Neutrality therefore seems a theoretical policy with no place in the real world of international dependence, global power politics and welfare economics. In short, to the critics, neutrality is not a credible wartime policy.

But neutrality is just as much, if not even more so, a peacetime policy. It might even be called peaceful. Armed solutions to political, ethnic, religious and other sources of conflict should not be supported. This view has lead to a particular neutral dilemma, which was very strongly exposed during the 1970s and 1980s, when the bigger European neutrals - Austria, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland - started making headlines for their foreign military sales. Whereas until then the neutrals had generally been known for restrictive military sales policies, they were now recognized for their increasing sales, especially to poor countries or regions of the world.

Contrary to previous national debates about foreign military sales, the issue did not quickly disappear. This has been particularly evident in Sweden. Before, debates had generally been ad hoc dealing with individual cases of military sales. The debates had been as short or as long as the public and media interest permitted, which in general was not very long. This time, however, new deals - both legal and illegal - came to the surface, partly through ‘investigative journalism’. Some of these cases created big question marks as to the involvement of military firms, governments and individuals. Foreign military sales, not individual cases, were taken up as a political issue by itself with consequences for neutrality as a legitimate policy and national armament as a solution to national security. More public and academic interest arose around the issue. The public as well as political groups and individuals demanded and suggested changes of policy, ranging from an unconditional embaigo on all foreign military sales to a more liberal (according to some more ‘realistic’) foreign military sales policy.

Neutrality as such was at the center of at least one of the suggested solutions, namely, that the neutrals should increase military sales among themselves in an attempt to reduce their global military trade. Such a ‘directed’ foreign military sales policy seems first to have been formulated in the mid-1980s by the Swedish Ecumenical Council. It has since then been incorporated into a more comprehensive ecumenical peace policy proposal (Fredspolitik for 90-talet 1989). The idea, which also encompasses the Nordic countries, has been taken up by other groups. The Swedish Prime Minister in September of 1986 supported the idea during a visit to Bofors, one of the main Swedish military producers (N-Syntesen 1986, no. 5, p. 4).

One of the ambitions of this book is to discuss whether such an alternative is possible and, if so, what it could possibly look like. But first, let us look at some of the more general issues involved.

1.1 The Larger Issues

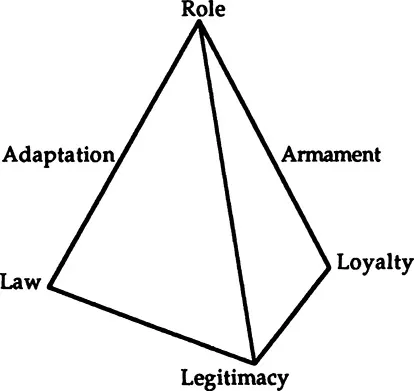

The issue of foreign military sales is related to important aspects of neutral foreign policy. The most crucial aspects can be summarized as ‘the Ľs, the A’s and the R’. They make up what is here called the LAR pyramid (figure 1.1).

It is probably uncontroversial to suggest that the neutrals want to appear special, even if it is not always possible to distinguish the finer day-to-day differences between the foreign policy of a neutral and the foreign policies of most other nations. When trying to do so, however, some issues appear more important than others. Perhaps most important of all is Law, here understood as international law. Without the respect for international law, neutrality is very much a policy without a meaning. This is particularly so for Austria and Switzerland, which have neutrality policies founded in international agreements. This is not the case for Finland and Sweden. Sweden has pursued a self-defined neutrality policy since the early nineteenth century. Finland’s neutrality was officially acknowledged by the Soviet Union in October of 1989. For none of them, however, can neutrality survive in wartime unless the warfighting states respect the lawful integrity of neutral states.

Figure 1.1 The LAR pyramid

Law is closely linked to Legitimacy. Neutrality must, in the same way as alliance membership, be accepted by others as a legitimate foreign and military policy alternative. The neutrals themselves must make the chosen policy look relevant and credible. Credibility is probably the most difficult aspect of neutrality, because it can be judged against any act, statement, even non-decision, by a neutral government. We will return to this.

In their policies, neutral governments have generally chosen the side of the smaller states. Part of the foreign policies of neutrals includes a special Loyalty toward exposed nations or peoples. One aspect of this Loyalty is the demand for a reduction of unequal distribution of wealth and influence and the support of basic human needs and rights. For instance, support of a more equal ‘economic world order’, much discussed during the 1970s, and solidarity with the problems and difficulties of the developing nations have been repeatedly expressed.

The three Ľs make up the base of the pyramid. They represent basic attitudes to important global issues. The two A’s imply that these attitudes have to be operationalized and implemented. That is a different and more difficult matter than to formulate policy. It is at this stage that the neutral dilemma becomes apparent.

Due to their small size and their international dependencies, the question of Adaptation to international transformation becomes crucial. Despite the difficulties involved in defining the meaning and measurement of dependence, it seems an uncontroversial conclusion that developments since 1945 have created increasing latent (potential) dependence of small states upon bigger states and groups of states (see for instance Keohane & Nye 1977; Jones & Willetts 1984; Hagelin 1986; Catrina 1988). Latent dependence is the potential for other governments and organizations to exert pressure upon the smaller states. Part of the dilemma stems from the fact that neutrality implies a certain degree of independence. But to what degree and with regard to what issues?

The answer to that question is at the center of legitimacy. The neutrals must make credible that their policy is an alternative to major-power-dominated policies. They must show that it is possible to retain a certain freedom of action. The general observation has been made that if participation in universal international organizations confers many benefits upon the neutral state while involving very few risks, action within regional organizations may in the long run tarnish the credibility of neutrality (Karsch 1988, p. 62). Such membership might be interpreted, by nations not part of such organizations as ‘block orientation’. This, in turn, would imply a reduction of neutral freedom of action and create doubts about the credibility of neutral independence.

Moreover, the more specific the interpretations of the three L’s, the less the political freedom in implementing them. Although membership in military alliances is, by definition, impossible for a non-aligned nation, membership in economic organizations is another matter. Although Sweden joined the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) without any reservations (Sweden also-participated in the Marshall Plan), Finland refrained from either accepting the Marshall Plan or joining the OEEC. Instead, it joined the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the successor of the OEEC. Switzerland, when joining the OEEC, clarified that the membership was not to be interpreted as a compromise of its neutrality (Karsch 1988, p. 63). All the neutrals have, however, joined the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

It seems that the less military the issue, and the less controversial with regard to national sovereignty and independence, the easier it has been for the neutrals to adapt to international changes by becoming members of international organizations or to formally cooperate in other forms. Participation in international as well as regional organizations in support of civilian research and development (R&D) or civilian industrial projects, for instance, has generally posed no insurmountable difficulties.

The European Community (EC), however, has been a more complicated matter. Whereas OEEC/OECD and EFTA were perceived of and presented as purely economic frameworks without political constraints, the EC is different. It aims not only at a regional community with a common economic policy and trade barriers toward non-members. It has also developed into a community with political and security, including military-industrial, facets (Sjöstedt 1977).

As a reflection of the dilemma between neutrality and the need for adaptation, it should be noted that although Ireland, another neutral state, is a member of the EC, Finland and Sweden have not accepted membership under the present circumstances. Instead, the EFTA countries are seeking a collective arrangement with the EC. The Swedish rejection of individual and formal membership was made clear in a statement by the then Foreign Minister on April 9, 1972, in connection with the signing of a trade agreement between Sweden and the EC (Documents on Swedish Foreign Policy 1972, p. 255). That statement repeated the basic arguments that had been presented by the Swedish Prime Minister in August of 1961 (Documents on Swedish Foreign Policy 1961, p. 119). Likewise, in October of 1988 the Finnish government presented a report to Parliament stating that close cooperation, but not membership, was possible and desirable (referred to in Upsala Nya Tidning, November 2, 1988).

Contrary to Sweden and Finland, the Austrian government applied for membership in the EC in ĵuly of 1989. The application included a demand for remaining neutral. The application has not only created a controversy among the EC members. The Soviet Union, one of the signa-tory powers of the Austrian State Treaty in 1955, stated in August of 1989 that Austrian membership in the EC would automatically cancel any possibility of Austria realizing its neutral policy. Whether this was a serious Soviet ‘threat’ or just an attempt to support the critics within the EC is difficult to say. In any event, to accept or to reject Austrian membership will clearly not be an easy decision for the EC to make. It will be a test case for other neutrals who regard membership as a future possibility.

The EC has sharpened the neutral dilemma between economic necessity and political desirability. The economic risk of ‘going it alone’ is considered high among industrial circles. To put the dilemma in extreme terms, when the EC countries complete the common market in 1992, other nations may have to chose between accepting isolation or seeking integration. Whether neutrals decide to ‘go it alone’ or to become members of international organizations, the dilemma remains. ‘Isolated independence’ may be no better than ‘integrated dependence’.

In general, the dilemma involved in adaptation can be phrased thus: how to behave in a changing world without risking the legitimacy of neutrality. Armament, the second A, poses that question specifically with regard to military policy. There are at least two contradictory attitudes toward the relationship between neutrality and armament. The first is that a neutral nation does not have, and does not need, a military defense. This attitude shows a lack of understanding of the more or less implicit demands upon a neutral state in international law and the existence of domestic interests in favor of armament in peacetime. One might even argue that the basic rational for the present indigenous military production in the neutral countries is not neutrality but the preservation of that industry itself.

The other attitude reflects a more academic approach, namely, whether a neutral country allocates more or less to defense than does a military alliance member. This approach does not build upon the first notion that neutrality as such implies no military defense. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) has concluded that the question is impossible to answer (World Armaments and Disarmament 1987, p. 135). Attempts have nevertheless been made to develop a method to solve this controversial issue (see Murdoch & Sandler 1986).

Adaptation and Armament combined pose one of the most serious dilemmas with regard to neutral policy. All of the four neutral countries studied here have accepted a policy of ‘armed neutrality’ supported by some indigenous military production. At the same time, they support international and regional arms control and disarmament. The neutral governments also have restrictive foreign military sales policies - military sales are to be regarded as exceptions rather than as the rule. But due to increasing costs and technological demands, a restrictive military sales policy complicates the ambition to support advanced indigenous military production. Foreign military sales may therefore become an increasingly important ingredient in sustaining ‘armed neutrality’ by indigenous means.

There are, in other words, serious political difficulties in combining the basic attitudes expressed by the three Ľs with the ambitions and difficulties involved in the two A’s. If the gap becomes too wide, the Role of neutrality may be at stake. The Swedish Prime Minister has acknowledged that pursuing an active policy for international disarmament and non-military solutions to conflict has become more complicated since Swedish arms have shown up in unacceptable recipient countries (Anförande 1988, p. 12). With reference to figure 1.1, in order to avoid some obvious dilemmas, the neutral Role must be defined as the logical extention of, and must be in harmony with, the basic attitudes and their realization. This harmonization involves both the formal and the actual policy.

Foreign military sales have therefore become an important issue in the policy of neutrality itself. The problems involved in foreign military sales relate to several general issues of importance to the role and standing of neutrality in the global society.

1.2 Foreign Military Sales

This study is about Austria, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland. These non-aligned states have accepted a policy of ‘armed neutrality’. This means a policy supported not only by military force but by certain indigenous military production. Domestic military research and development (R&D) as well as manufacture have been defined as important for the credibility of an independent and armed non-aligned policy in peace-time and successful neutrality in wartime.

But the economic and technological conditions for armed neutrality have changed since 1945. Inflation, personnel costs and the cost of new technology have increased the financial pressure upon sustaining a military establishment in general and military production in particular. Military materiel has become more expensive (Olsson 1977; Hagelin 1985). Government orders for indigenously developed military materiel have therefore become less frequent and less automatic. The result is a dilemma for the neutral governments in adapting to changing economic and technological circumstances on the one hand, and armament as a national policy, on the other. This dilemma is the result of the push and pull between what is perceived as economic necessity and political desirability. George Thayer in 1970 remarked about the ‘ironies of the arms trade’ that Sweden and Switzerland, both neutrals with long histories of peace, were then among the world’s most agressive suppliers (Thayer 1970, p. 21). In 1978 Anthony Sampson noted with particular reference to Sweden that pressures would increase further on the dilemma of combining armed neutrality with commercial viability as the cost of self-suffic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The REFORMIS Approach: A Framework for Understanding Neutral Foreign Military Sales Policy

- 3 Modern History and Military Buildup

- 4 Foreign Military Sales

- 5 Cooperation or Competition

- 6 Conclusions and Discussion

- Appendix Tables

- Bibliography

- Index