- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book presents the results of the "African Urban Management" project designed to study comparatively governmental responses to the gap between the realities of official plans and perspectives and the mushrooming world of the urban poor in African cities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access African Cities In Crisis by Richard E. Stren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & African Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I

The Influence of Environmental and Economic Factors on the Urban Crisis

Rodney R. White

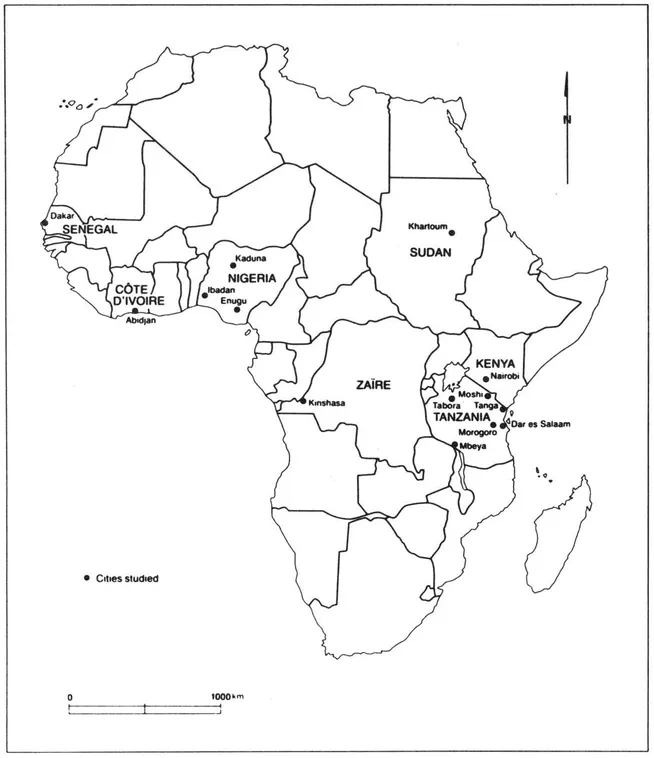

Figure 1.1 Cities Studied by the African Urban Management Project

CHAPTER I The Influence of Environmental and Economic Factors on the Urban Crisis

Rodney R. White

The economic plight of sub-Saharan Africa is a problem of growing concern Economic stagnation coupled with rapid population growth has produced a grave crisis on which there is widespread agreement as to the condition but little agreement as to the best mix of policies. Indeed, so much has been written recently on policy proposals for Africa that the critique of these proposals has itself become a growth industry for academics (Ravenhill 1986).

The following statement from a World Bank report is a typical appraisal of the symptoms of the problem:

Africa's economic and social conditions began to deteriorate in the 1970's, and continue to do so. GDP grew at an average 3.6 percent a year between 1970 and 1980, but has fallen every year since then. With population rising at over 3 percent a year, income per capita in 1983 is estimated to be 4 percent below its 1979 level. Agricultural output per capita has continued to decline, so food imports have increased; they now provide a fifth of the region's cereal requirements. Much industrial capacity stands idle.... Many institutions are deteriorating, both in physical capacity and in their technical and financial ability to perform (World Bank 1984a, 1).

The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of the process of urbanization at this difficult time. The manner in which urban policy options are constrained by current conditions needs to be understood, and the effects of past urban policy need to be examined.

Since the "urban bias" in national policies was identified (Lipton 1977; Dumont and Mottin 1983), the tendency has been to assume that if the bias could be reversed then conditions would improve; answers have included "integrated rural development," "true market prices," and many more. Yet as each incorrect policy has been identified and a new watchword proposed, the problems have grown deeper. To any informed observer over the past fifteen years, the process has resembled the peeling of an infinite number of layers of the onion skin.

Clearly, no single cause explains the population growth and economic decline syndrome from which sub-Saharan Africa is suffering. Rapid societal change on a continental scale is a complex process, and many variables must be considered simultaneously. It is not a question of determining whether the rural sector or the urban sector is the most important; an understanding of their symbiotic relationship is required. Neither "integrated rural development" nor "privatization" nor "letting the market operate" is going to solve the problem. The fact is that the economy and society suffer simultaneously from a lack of foreign exchange and from a shortage of clean drinking water among many other needs.

In this sort of situation, it is foolish to champion tourism (for example) as the best foreign-exchange earner, without first considering whether the urban system is salubrious enough to support a tourist industry and whether the water demands of tourism can be met from available supplies. One cannot let the urban system crumble to the point that it cannot support rural development, while channeling all available funds into the rural sector. Unfortunately, the solution is much more complex than the simple either / or alternatives that have so often been considered in the last fifteen years.

Through a set of case studies, this study attempts to examine the interplay of many factors – domestic policies as well as exogenous events such as changes in the price of oil and severe fluctuations in rainfall. The remainder of this chapter looks at population growth, environmental stress, and the economic trends. The two subsequent chapters examine the political and administrative framework in which urban management takes place. These are followed by seven case studies and a concluding chapter.

Population Growth and Urbanization

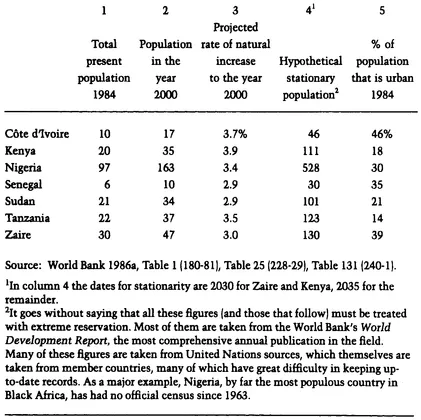

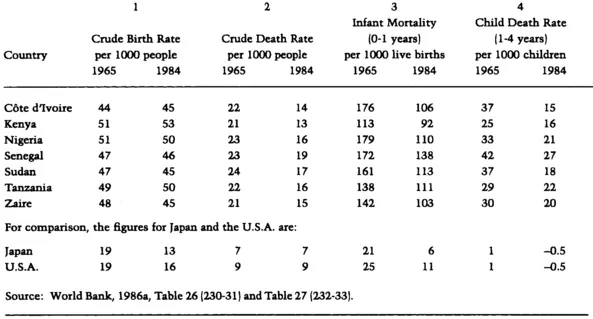

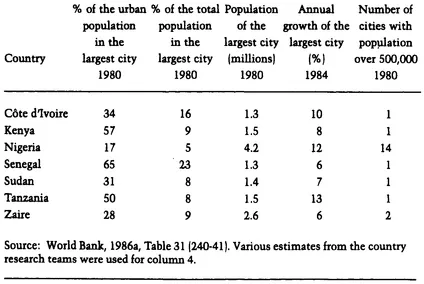

For sub-Saharan Africa, the two key demographic events of the period 1950 to 198s are steady population growth and increasing urbanization (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2). Although the region is not highly urbanized by global standards, the trend in that direction has been extremely rapid. Also notable is that, in conformity with world trends, the largest cities have generally been growing fastest. In this case, one would expect the largest city within the national urban hierarchy to become increasingly dominant. Table 1.3 shows the degree of dominance of the major cities in 1980 - the latest date for which comparable data were available.

In only two of the countries covered in this study – Nigeria and Zaire – is any regional manufacturing complex large enough to counter-balance the attractiveness of the largest major city to migrants. (see Table 1.3, column 5 for an indication of this tendency.) Because of this dominance, the majority of import-substitution activities are drawn to the major city, thus reinforcing its demographic weight. Although no less than three of the seven countries have re-located their national capitals to interior locations, none of these new foci has emerged to challenge the former capital (Attahi 1984).1

Since the 1960s studies have emphasized the economic rationality of the

Table 1.1 Population Growth and Urbanization (millions)

Table 1.2 Some Indicators of Demographic Change

migrant's move to the big city (Todaro 1976); other studies have emphasized the agglomeration economies that the large cities would produce (Linn 1982). There was no immediate concern that the cities were growing too fast or would become too large, as it was believed that a deterioration in the urban quality of life would produce a decline (perhaps even a reversal) of rural-urban migration. It was also believed that rapid urbanization would stimulate the demand for goods from the domestic rural economy. Eventually, rural wages would rise, and a tendency towards equilibrium would appear, thus encouraging an orderly transition to a Western-style, urbanindustrial economy in Africa.

Table 1.3 The Population of the Largest City

That nothing of the kind has occurred may be attributable to the omission of some exogenous variables from the macro-economic models on which such beliefs were based. (See next section for further elaboration.) A number of important endogenous processes were also under-estimated by the same models. The most important for understanding the urban trajectory is what became known as the "urban bias," as mentioned above. Under this type of policy, governments established price controls to protect urban consumers from inflation. Some simultaneously kept a fixed rate of exchange at above market level. The combination of these two factors encouraged the growing reliance on cheap, imported food with which the domestic farmer could not compete – especially in the provision of grains. This is now believed to have contributed substantially to the decline of the rural economy.

Thus, the redistribution process which began with a strong movement to the cities in search of newly-created jobs in industry and services became entrenched by the steady decline of the domestic rural-urban terms of trade and the decline of agricultural export markets. Since 1985 some governments (under strong pressure from the IMP) have tried to reverse this trend by raising farmgate prices, adopting more realistic foreign exchange rates, and reducing heavily subsidized urban services.

Despite all the uncertainty surrounding economic and demographic trends, the World Bank and other international agencies produce projections of stationary populations. (At stationarity, births equal deaths.) These projections must resemble a nightmare to urban planners (see Table 1.1, column 4). If the percentage of the total population in the largest city (Table 1.3, column 2) were to remain at the 1980 level, then the following city populations would be recorded by the time stationarity occurred (estimated for between the year 2030 and the year 2035):

| (estimated population in 1980) | ||

| Abidjan | 7 million | (1.3 million) |

| Dakar | 7 million | (1.3 million) |

| Dar es Salaam | to million | (1.5 million) |

| Khartoum | 8 million | (1.4 million) |

| Kinshasa | 12 million | (2.6 million) |

| Lagos | 26 million | (4.2 million) |

| Nairobi | 10 million | (1.5 million) |

If this growth should seem improbable, it is instructive to remember that Mexico City is estimated to have a population of 18 million and is projected to grow to 26 million by the year 2000 (Salas 1986, 20). (There too, the engine of growth is not the expansion of the urban economic base, but demographic inertia and the perceived lack of economic opportunity in the rural areas.) The World Bank estimates: "by [the year] 2000 ... Dakar and Nairobi are likely to have more than 5 million inhabitants each, compared with between 1 million and 2 million today" (1986b, 10).

It would seem that the best that can be hoped for is a higher level of urbanization which, if living standards can at least be maintained, will encourage a rapid fall in infant mortality and a fall in fertility. Under this scenario, the biggest cities will continue to grow (perhaps even to the size indicated above). Although the links among mortality, fertility, and population change are disputed, there is general agreement that "most programs and policies undertaken to reduce mortality will, in most settings and over the long run, produce even greater fertility declines and thus slower growth" (Gwatkin 1984, Abstract).

The question for urban planners and other policy-makers is: How can urban growth be managed in such a way that it does not occur to the detriment of the rural economy, the surrounding environment, and the urban system itself? The next section will consider some of the key environmental variables on which the sustainability of the urban systems directly depends.

Environmental Stress

Economies do not develop within an unchanging "environment." Economists used to designate certain inputs like air and water as "free goods." Now that clean air, water, woodfuel, untilled land, and wild game are no longer so plentiful, the "value" of the environment is being recognized. Nowhere is this realization more apparent than in Africa. The seven countries examined in this book have similarities and differences not only in their economic context but also in their environmental situation. The commonalities are presented in order of importance.

In an urban environment, the water supply is the most crucial element. As cities expand, they incorporate the neighboring villages, in which the people followed a rural way of life and drew water from local wells. Gradually, the population density outstrips the capacity of the wells. The groundwater, which drains into the wells, becomes more subject to pollution. Also, as Oumar Wane (1983) has pointed out about Dakar, the extension of the asphalted area reduces the amount of rainwater that can seep through to recharge the local aquifer.

As local water sources are outstripped by demand and by pollution (or as in the case of Dakar, by over-pumping and salt-water intrusion), the search for piped urban water extends gradually into the surrounding region. This extension has three negative implications. First, it will draw water from areas in which other (smaller) communities already have established demands. Second, the urban demand may overpump the aquifer, in comparison with the known re-charge rate. Third, the further the water must be transported, the more it will cost.

Another major element of the urban environment is waste disposal. This issue is only just becoming important in highly industrialized countries (at the regional scale). Until recently, waste disposal was a small-scale issue that could be taken care of within the municipal boundaries. In Africa, traditionally, as villages grow into towns, the authorities simply pick up the rubbish and dump it on the roadside at the edge of the built-up area. However, as cities pass the million mark in population, this is no longer a local issue. Space for large, sanitized waste disposal is required on a regional scale, planned over a twenty-year period. If such plans cannot be made, then two problems build up. First, the level of conflict between the municipality and the surrounding jurisdictions heightens. Second, pollution of the groundwater from the seepage from overfilled (and under-designed) waste disposal sites increases.

The situation in Ibadan is perhaps typical. A dump established in the early 1960s near what was then the city's "by-pass" road is now completely surrounded by housing. Not only is the dump still being used but also the waste is not covered over. The "new site" five kilometers further from the center is also surrounded by housing. A search is now under way for a site twenty kilometers from the city center. However, this will sharply increase capital costs for more vehicles and running costs for fuel, personnel, and the like. In Dakar, the same phenomenon is evident. The municipal dump is located fifteen kilometers from the city center, yet it will soon b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Currencies

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1. The Influence of Environmental and Economic Factors on the Urban Crisis.

- CHAPTER 2. Urban Local Government in Africa.

- CHAPTER 3. The Administration of Urban Services.

- CHAPTER 4. Urban Growth and Urban Management in Nigeria.

- CHAPTER 5. Côte d'Ivoire: An Evaluation of Urban Management Reforms.

- CHAPTER 6. Kinshasa: Problems of Land Management, Infrastructure, and Food Supply.

- CHAPTER 7. Appropriate Standards for Infrastructure in Dakar.

- CHAPTER 8. Local Government and the Management of Urban Services in Tanzania.

- CHAPTER 9. Management Problems of Greater Khartoum.

- CHAPTER 10. Urban Management in Nairobi: A Case Study of the Matatu Mode of Public Transport.

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Contributors

- About the IFIAS

- Index