The history of child abuse: an overview

The abuse of children by adults is generally considered by any standards to be a very long-standing phenomenon. However, reflection on child abuse in an historical context almost always entails a retrospective evaluation of behaviours against contemporary standards. The types of illustrations of the way children were treated in the past, and which so often produce sadness, horror, pain and indeed, sometimes pure outrage, are probably best viewed as indicators of the types of behaviours that were permitted, condoned or even encouraged by the societies in which they took place. As described by a number of writers, childhood (and therefore child abuse as a particular experience of childhood), is a socially constructed phenomenon (Stainton Rogers 1989; Parton 1985). These social constructions are also a reflection of the relationship between the child and the state/society within which he or she lives. It will be helpful therefore to put some of the examples given of how children were abused in the past into a social context.

The beginning of any consideration of children in relation to society begins with the nature of childhood as viewed in society, a discussion following the work of Aries (1962), DeMause (1976) and Pollock (1993). It is the contention of Aries that children were not viewed as children in medieval society because there was no conception of childhood as such: ‘in medieval society the idea of childhood did not exist’ (p.125). In such a model, children share the same fates as adults (wars, famines, plagues, etc.) without discrimination by virtue of their younger status. They may be newer individuals to arrive within that society, but other than that, they are not different.

Pollock considers that there are shortcomings in Aries’ contention, because of methodological considerations. She suggests there has been a conception of childhood in medieval times, even if reflection of that was absent in the kind of material used for data by Aries. She is not alone in her refutation of Aries’ contention, and Cunningham suggests in relation to Aries’ quote above: ‘Rarely can so few words have brought forth so many in refutation’ (1995: 30)

DeMause (1976) noted the scarcity of material on parent-child relations in history, and considers the nature of parent-child relationships as an evolving phenomenon, the evolution of which is dependent upon a process he describes as ‘psychogenic’. In this theoretical framework, the inter- generational processes influencing how people parent contribute to an overall development of parenting across the ages. He considers that this process contributes to an overall improvement for the welfare of children: ‘... if today in America there are less than a million abused children, there would be a point back in history where most children were what we would now consider abused’. (DeMause 1976: 3)

Let us look at some of the examples cited of child abuse in historical times. The most extreme form of abuse is child homicide. There are several references in the Bible to the large-scale extermination of children, by Pharaoh at the time of the birth of Moses, and by Herod at the time of the birth of Jesus. There are also biblical references to child sacrifice (Jericho 7: 32; 2 Chronicles 28: 3; Joshua 6: 26; 1 Kings 16: 34). Tower (1996) refers to the biblical story of Isaac, who was at the point of being sacrificed by his father, Abraham, and was only stopped by the intervention of an angel who told Abraham it had been a test of faith (Genesis 22:1-19).

DeMause (1976) considers that the extent of infanticide in antiquity is generally under-recognised and he considers that the practice extended well into the Middle Ages:

The Bible also contains references to children being interred in the walls and gates of Jericho: Tn his days did Hiel the Bethelite build Jericho: he laid the foundation thereof in Abiram his firstborn, and set up the gates thereof in his youngest son Segub’ (1 Kings 16: 34). Both Bakan (1971) and Radbill (1974) refer to the practice across centuries and cultures of interring newborn infants into walls of buildings and bridges to strengthen the structures. Several writers (DeMause 1976; Zigler and Hall 1989) refer to this practice as the basis for the children’s nursery rhyme/song, ‘London Bridge is Falling Down’.

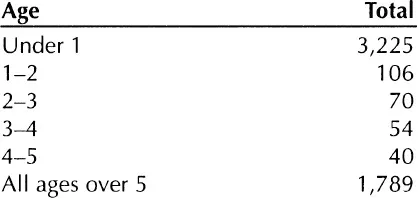

Tower (1996) refers the power of fathers in ancient Rome to kill, abandon or sell their children, although as pointed out by Doxiadis (1989) because of the Roman Empire’s need for people to carry out its plans for conquest, measures were taken to forbid the practice of infanticide. Infanticide in some cultures (Hawaii, China and Japan, for example) was seen as a means of regulating the population, a form of survival of the fittest. Doxiadis (1989) suggests that whilst the practice in ancient Greece was forbidden, it was practised nevertheless. Others have considered it to be so extensive as to have been a cause for the very small population of ancient Greece. Doxiadis highlights the difference in attitudes towards infanticide in the ancient world being based on whether the society needed more people or not. Lee et al. (1994) note that the Qing lineage during the eighteenth century regularly used infanticide to control the number and sex of their infants. Radbill (1980) describes a number of cultures (British New Guinea, Germany, North American Indians) in which there was a test of viability of the newborn child, the consequences of failing the test being death. In other societies, the child was not protected until given a name. Zigler and Hall (1989) also give several examples of the child’s right to live being determined shortly after being born, usually by the father. The practice of infanticide was so widespread as to render the first year of an individual’s life as the time of greatest likelihood to be killed. The following table is reproduced from Rose (1986):

Table 1.1: Total deaths from homicide in England and Wales 1863-1887 (Rose 1986)

He notes ‘Thus the under-l’s formed 61 per cent of all homicide victims, at a time when they constituted 2.5-3 per cent of the population’ (Rose 1986: 8). When combined with other causes of child mortality, (disease, starvation), it led Walvin to observe that ‘the death of the young as well as the old, was an inescapable social reality in nineteenth-century England’ (1982: 21-2). The death rate for children under one year of age, is shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Infant mortality rates (death of children under one year of age from all causes) (Parton 1985)

| Year | Deaths under 1 year of age per 1000 |

| 1839-40 | 153 |

| 1896 | 156 |

| 1899 | 163 |

Interestingly, Cunningham (1995) notes that while infant mortality rose in England and Wales (along with Belgium and France), in other European countries (Austria, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden) it fell during the same period. Parton (1985) notes that 1899 was a peak during the period when rates were recorded, followed by a decline, although Cunningham (1995) estimates that it was considerably higher (between 250 and 340) during the seventeenth and early eighteenth century

Disability and illegitimacy were particularly likely to condemn a child to death in a wide range of cultures and societies. In Greece children with a disability could be especially vulnerable to infanticide; Aristotle in The Politics stated: ‘With regard to the choice between abandoning an infant or rearing it, let there be a law that no cripple should be reared.’ Zigler and Hall (1989) note that the Roman Laws of the Twelve Tables forbid the rearing of a child with a defect or deformity. As DeMause describes it: ‘... any child that was not perfect in shape and size, or cried too little or too much, or was otherwise than is described in the gynaecological writings on “How to Recognize the Newborn That is Worth Rearing”, was generally killed’ (1976: 25). In Moral Essays, Seneca wrote, ‘sickly sheep we put to the knife to keep them from infecting the flock; unnatural progeny we destroy; we drown even children who at birth are weakly and abnormal.’

The connection between illegitimacy and infanticide was so strong in both England and America during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that where an unmarried mother gave birth to a child alone and the child was later found dead, the mother was regularly accused of murdering the child (Jackson 1996). In England, it was the presumption in law (a statute of 1624) that the child was deemed to have been murdered by the mother unless the mother was able to prove that the child was stillborn. This was reversed in 1803, so that evidence was required of the child’s live birth before a woman could be convicted. Whilst many women were hanged for such an offence, the twentieth century saw a reversal of the previous severity. With the Infanticide Acts of 1922 and 1938, women were able to be convicted of a lesser offence, ‘Infanticide’, a variation of manslaughter, rather than murder.

Gender was another factor that in certain places at certain times may have condemned a child to a short life. Whereas illegitimate children, whether male or female, were always equally likely to have been exposed, in the case of legitimate children, only girls were vulnerable, a preference across most societies being an institutionalised preference for males over females. According to Payne (1928) the Chinese banned infanticide under the influence of European missionaries, but we have seen a resurrection of this practice in recent years with the advent of the one-child policy. It has been suggested that the exposing of female children may have accounted for the very large gender imbalances during the Middle Ages (156 males to 100 females in 801; 172 males to 100 females in 1391). Radbill comments, ‘Girls were especially at risk ... far more likely [than brothers] to be killed, sold or exposed’ (1980: 6). Poffenberger notes the extremity of the practice in India after the turn of the nineteenth century: ‘The outstanding example of female infanticide in Gujarat was practised by the Jhareja Rajputs of Kathiwar and Kaach, where a census taken by the British administrators in 1805 found almost no daughters’ (1981: 79).

The distressing sight of ‘half-clad infants, sometimes alive, sometimes dead, and sometimes dying, who had been abandoned by their parents to the mercy of the streets’ (Pettifer 1939: 31), led Thomas Coram to found the first British foundling hospital in 1739. Similar institutions had been, or were being set up in Paris (Rose 1986; Marvick 1976), Dublin (Rose 1986), Moscow (Dunn 1976), St Petersburg (Radbill 1980) and other European capitals. The first recorded foundling hospital was established in Milan in 1787 (Radbill 1980). As pointed out by Cunningham (1995), the foundling hospitals were predominantly set up in Catholic countries where policies facilitated the abandonment of infants. Despite the establishment of foundling hospitals, the chances of survival for foundling children were very small indeed. In the case of the London Foundling Hospital, for example, the survival rate for foundlings was 52 per cent, though Cunningham (1995) notes the rate was as low as one-third during the five years following the opening of the doors to larger numbers in 1756.

Although historically, children had a very difficult time of surviving, if they did survive, then the likelihood of being the target of sexual usage by adults was quite high: ‘The child in antiquity lived his earliest years in an atmosphere of sexual abuse. Growing up in Greece and Rome often included being used sexually by older men’ (DeMause 1976: 43). But the involvement of children in adult sexuality was by no means limited to those societies, and DeMause gives examples from other cultures as well. Tower (1996) notes the difference between the sexual usage of children in Rome and Greece: in Rome, sexual relations with children did not raise their status, as it did in Greece. Radbill (1980) describes a number of cultures in which daughters (as well as wives) were loaned to guests as an act of hospitality. Christianity, drawing on the teachings of Christ, was largely responsible for the development of the view of children as ‘innocents’, and therefore needing protection. DeMause (1976) highlights the parental role in the sexual usage of children, whether through the sale of children for sexual purposes or other means. He notes that one effect of such usage can be child prostitution, an issue which has raised concern recently, but is not new. Myers (1994) considers the work of Dr Ambrose Tardieu to be the first modern acknowledgement of child sexual abuse. In 1857, Tardieu published a book chronicling thousands of cases, but despite his eminence and prestige, his beliefs were challenged and dismissed by his successors. Cunningham (1988) notes that both Tardieu and later Binet (another nineteenth century child development specialist who pioneered work on children’s intelligence) saw the seriousness of child sexual abuse, attempted to ascertain how widespread it was, and upheld the credibility of children’s accounts about the abuse they had experienced.

There are other forms of ill-treatment of children which have come to be defined as abusive from a contemporary perspective. DeMause (1976) provides a very good overview of the severity of discipline meted out to children. The value of beating children was widespread and shared, ostensibly for the purpose of improving their character, but one wonders if it was not often administered for more sinister motivations. Child labour is another form of ill-usage of children that has been the subject of concerns in the past. Considerable campaigning and lobbying went into efforts to protect children from the relatively unrestrained application of market principles by employers during the Industrial Revolution. For many such employers, the lower wage costs associated with child labour was a sudden and welcome increase of profits, which more than balanced the cost in human misery of which they may or may not have been aware.

The philanthropic campaign to eliminate child labour is one point of similarity amongst many in the development of child welfare social policy between Britain and the US. At first, one is perhaps inclined to be surprised at how many similarities, despite very different governmental frameworks, there are between the way both British and American child protection measures have developed. And yet, despite hostilities arising from several wars (The War of Independence, the War of 1812, and even as late as the American Civil War), there have been strong affinities arising from a common background, a common language and considerable commercial interests. In comparing the British child protection system with those in Europe, I have suggested elsewhere that ‘Historically, Britain has looked across the Atlantic rather than across the Channel for ideas and inspirations regarding child welfare practice’ (Sanders et al. 1996b: 900). The remainder of this section should provide a foundation for that assertion. We now turn to consider those separate, but strikingly parallel developments.

American approaches to protecting children from harm

Although it is my intention to highlight similarities between the American and British approaches and backgrounds of child protection, we must begin with a big difference. Within the American framework, child protection is a state issue, and although there may be considerable consistency across states facilitated largely by federal legislation and funding (for example, on mandatory reporting), there is considerable scope for different states to vary how they undertake child protection (as we will see in the next section). The extent of similarity or difference in the UK framework depends upon the level of analysis. It would be fair to say that because there are different statutes applying to the three regions, Scotland, England and Wales, and Northern Ireland, they have different subsidiary guidance addressing how child protection work should be undertaken. However, if one draws the parallel between local authorities and central government, then the parallel breaks down, as local authorities work to the same set of legal guidelines, determined by central government.

Physical abuse in the US

It is tempting to consider that the major impetus for American child protection begins with the case of Mary Ellen in 1874, which I will consider shortly. First I wish to explore the preconditions that helped to make those events so s...