- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A comprehensive school, like any community, is split into many groups and sub-divisions and contains many different 'social worlds' within its structure.

First published in 1983, this work is based on a one-year project carried out by the author which involved observation of pupils in lessons and interviews and informal conversa

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Social World of the Comprehensive School by Glenn Turner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Research On Pupils: An Assessment of Current Models

There are two well developed models which can be utilized for the analysis of pupil activity, both of which have a considerable history but remain in vogue. One is the adaptation model, originating from Merton's (1938) work, and the other is the subculture model, developed by Albert Cohen (1955) and Walter Miller (1958). Both of these models derive from normative functionalism, a sociological approach first systematized by Talcott Parsons (1951). However at the same time they represent modifications of the Parsonian position, attempting a more satisfactory account of deviance. In Parsons' theory, stability of the social system is achieved through the existence of norms which are internalised by all members of society. Deviance occurs as a result of the failure of norms to control behavior. Parsons identifies the main causes of such failure as inadequate socialisation, strains arising from difficulty in acting in accordance with norms which frustrate personality needs (such as affection and dependency) and strains arising when normative standards are ambiguous or in conflict. However as Lockwood (1956) points out, Parsons concentrates on normative aspects of social structure and process and ignores non-normative elements. As a consequence causes of deviance are located in personality mechanisms, and social processes which systematically generate deviance and social change are ignored. The subculture and adaptation models represent a departure from normative functionalism in that they are concerned with the social production of deviance.

The Adaptation Model

Merton (1938) sets out to demonstrate that some members of society are actually under social pressure to engage in deviant behavior. He develops this argument from Durkheim's ideas, taking the notion of anomie as a central concept. Anomie, for Durkheim, occurs where the moral framework does not effectively regulate people's desires and aspirations. One result is that desires are insufficiently restrained and individuals become subject to the 'malady of infinite aspiration' forever striving but forever dissatisfied because their goals are limitless. This pathological state is characterised by unhappiness, illness and, in extreme situations, suicide. Durkheim argued that a high level of anomie is a transitional feature of the shift from mechanical to organic solidarity.

Although Merton's model Is presented as a development of Durkheim's work, the way in which he uses the concept of anomie is in fact rather different. Whilst Durkheim was concerned with the failure of individuals to be bound by norms, for Merton anomie is conceptualised as a breakdown in the relationship between societal goals and means. He argues that society remains in equilibrium as long as individuals derive satisfaction from conforming to both culturally defined goals, purposes and interests and the acceptable modes of achieving these. However, in some societies, he argues, greater stress is placed on the value of specific goals than on the culturally defined means of achieving them and this tends to result in attempts to achieve goals by illegitimate means. Merton holds that American society is characterised by such disequilibrium. There is greater emphasis on financial success than on the means of achieving it and this imbalance is reflected in the high crime rate. Furthermore his theory is able to explain why crime is more prevalent among the lower classes. He argues that because the lower classes are motivated towards pursuit of the goal of financial success but lack the formal education and economic resources to achieve it, they experience greater pressure to adopt illegitimate means.

Merton identifies a number of different orientations individuals might adopt in relation to culturally defined goals and legitimate means:

We here consider five types of adaptation, as these are schematically set out in the following table where (+) signifies "acceptance", (-) signifies "rejection", and (±) signifies rejection of prevailing values and substitution of new values.

A Typology of Modes of Individual Adaptation

| Modes of adaptation | Culture goals | Institutionalized means | |

| I | Conformity | + | + |

| II | Innovation | + | - |

| III | Ritualism | - | + |

| IV | Retreatism | - | - |

| V | Rebellion | ± | ± |

(From R. K. Merton, 'Social Theory and Social Structure', Free Press, 19573 p.140)

In Merton's view conformity is the most common adaptation in a stable society. Innovation occurs when there is emphasis on goals without the culturally defined means having been internalised. On the other hand if the cultural goals are abandoned, or scaled down, but acceptable means are internalised, the adaptation is ritualism1.. Retreatism is a consequence of continued failure to achieve goals by legitimate measures but inability to adopt the illegitimate route because of internalised prohibitions. In this case goals and means are both abandoned but still imbued with high value. Rebellion is classed as being on a different plane to the other adaptations and represents a transitional response. Here both goals and means are rejected and efforts made to change the cultural and social structure.

The Subculture Model

The subculture model originates from early work on gangs in Chicago2., but came to be redeveloped as an alternative to Merton's theory. Both Cohen (1955) and Miller (1958) advanced theories accounting for deviance through membership of subcultures, although the two accounts are rather different. Cohen began by assuming, with Merton, that working class boys internalise middle class values. However he found that delinquency does not correspond to any of Merton's categories of adaptation. In particular, unlike crime it was generally 'non-utilitarian, malicious and negativistic', and thus could not be characterised as innovation. Consequently Cohen sought an alternative explanation integrating the psychological concept of 'reaction formation' into an essentially sociological account of the causation of delinquency.

He argued that working class boys are unable to succeed in middle class terms because they lack the necessary resources to reach high levels of achievement in school. This inability to succeed produces 'status frustration' which in turn leads to 'reaction formation'. They react against conventional values, creating a subculture in which status is derived from flouting rules. In this way the problem of status frustration is partially resolved. Delinquent boys, then, take the norms of the larger society and invert them, hence the 'non-utilitarian, malicious and negativistic' character of their behavior.

Whilst for Cohen delinquency stems from a delinquent subculture generated by groups of working class boys, for Miller it arises from working class culture itself. He argues that the 'focal concerns' of working class culture are in fundamental opposition to middle class standards and are conducive to delinquency. These focal concerns are identified along with their perceived alternatives:

| Area | Perceived Alternatives (State, Quality, Condition) | |

| 1. Trouble: | law-abiding behavior | law-violating behavior |

| 2. Toughness: | physical ptress, skill; "masculinity"; fearlessness, cowardice, bravery, daring | weakness, ineptitude; effeminacy; timidity, caution |

| 3. Smartness : | ability to outsmart, dupe, "con"; gaining money by "wits"; shrewdness, adroitness in repartee | gullibility, "con-ability"; gaining money by hard work; slowness, dull-wittedness , verbal maladroitness |

| 4. Excitement: | thrill; risk, danger; change, activity | boredom; "deadness" , safeness; sameness, passivity ill-omened, |

| 5. Fate: | favoured by being fortune, being "lucky" | "unlucky" |

| 6. Autonomy: | freedom from external constraint; freedom from superordinate authority; independence | presence of constraint; presence of strong authority; dependency, being "cared for" |

(From W. B. Miller, 'Lower Class Culture as a Generating Mileu of Gang Delinquency', Journal of Social Issues, Vol 14, no 3, 1958, p.84)

The commission of crimes by delinquent gangs, Miller asserts, is motivated by attempts to achieve the valued states and to avoid those disvalued. Given these focal concerns, getting into trouble, being tough, outwitting others, flirting with danger, taking risks and resisting authority are prestige-conferring. In Miller's view, then, delinquency is an almost inevitable outcome of socialisation into working class culture.

Applications of these Models to Schools

The Subculture Model

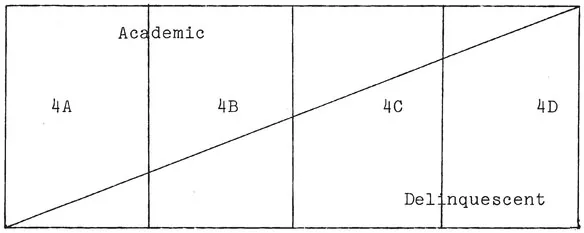

The argument that delinquency is a product of membership in a subculture was taken up in studies of schools by Hargreaves (1967) and Lacey (1970). Drawing on Cohen, Hargreaves argues that lower stream pupils take upper stream values and invert them with the consequence that two opposed subcultures emerge, one 'academic' and the other 'delinquescent'. This process is presented as a product of streaming. Hargreaves shows that friendship groups in school relate strongly to membership of streams and that within different streams there are different informal status hierarchies. These hierarchies reflect the norms which are dominant in each stream. In the A stream academic norms prevail, whereas those of the C and D streams are anti-academic, with the Β stream representing a compromise between the two extremes. Hargreaves shows that the higher the stream the greater the tendency for high status to be associated with attitudes, values and behavior expected by the school. On the other hand, in lower streams high status is associated with deviance. Over the course of their four years in school, pupils are subjected to a process of subcultural differentiation so that by the end of the fourth year most pupils belong to one of the two subcultures. These subcultures are to a large extent stream based, the academic subculture being most highly represented in the A and Β streams and the delinques cent subculture predominating in the C and D streams. (This is represented in Figure 1.1.)

Figure 1.1: Representation of the Two Subcultures Source: Hargreaves, D. H. Social Relations in a Secondary School, RKP, 1967, p. 163

Similar conclusions were reached by Lacey (1970) in his study of 'Hightown Grammar'. Lacey argues that pupils are subject to processes of 'differentiation' and 'polarisation'. Differentiation is the process of separation and ranking of pupils according to the normative value system of the Grammar school. In particular pupils are assessed on an academic scale and a behavior scale. The two tend to be related since teachers are inclined to favour and devote more time to those who work hard. Differentiation leads to a situation where pupils at opposite ends of the differentiated group are faced with different problems - of success and failure. Polarisation is in part produced by attempts to resolve these problems. It is a process of subculture formation whereby the academically oriented normative culture of the school is opposed by an 'anti-group' culture. By the end of the first years when streaming by ability takes place, the A stream comes to reflect most strongly 'pro-school' values and the D stream 'anti-school' values. Furthermore working class pupils tend to end up in the lower streams.

The anti-group starts to emerge in the second year and develops markedly in the third and fourth years. It is reinforced by 'adolescent' culture, 'pop' culture and by working class values. Lacey argues that middle class pupils are less likely to join the anti-group because their home background supports the same values as the school. Working class pupils, on the other hand, can draw on working class values and adapt them in opposing the values of the school. Here Lacey's analysis seems to incorporate Miller's argument.

Lacey's evidence makes an even stronger case than that of Hargreaves for showing the effects of the school organisation in producing 'conformist' and 'deviant' subcultures. Hightown Grammar selected only those pupils who had been successful in the eleven-plus examination and these pupils can be pressumed to have been strongly attached to school values in their primary schools. It is surprising therefore that after one year in the Grammar school some of them, especially those placed in the bottom stream, began to display anti-school values.

Despite a number of changes in the sociology of education since the work of Hargreaves and Laeey, basically the same bi-polar model of pupil orientations has been presented in more recent studies. Thus, for example, Ball (1981) identifies similar processes of differentiation and polarisation in a comprehensive school. Through an intensive case study of 'Beachside Comprehensive', he argues that the lowest academic positions in the school become increasingly composed of 'anti-school' pupils. Ball demonstrates this with evidence of changes in friendship choices, changes in 'clique' membership and changes in the distribution of academic success, in two case study forms. In addition he notes that working-class pupils tend to be drawn towards the 'anti-school' pole. Although mixed ability grouping was introduced at Beachside this peters out as pupils progress through the school, whilst for some subjects setting is adopted. In any case so long as teachers believe that there are different 'types' of pupils, ascriptive tendencies continue within mixed ability classes. Ball argues that because pupils are still selected and separated, at Beachside the egalitarian aims of comprehensivisation are not realised.

Where Hargreaves, Lacey and Ball r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Research on Pupils: An Assessment of Current Models

- 2. Method and Setting

- 3. Pupil Activity in Context

- 4. Pupil Goals and Interests in School

- 5. Swots and Dossers

- 6. Conclusion

- Appendix: The Role of the Researcher in the Setting

- Bibliography

- Index