eBook - ePub

Strawberries

Production, Postharvest Management and Protection

- 548 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Strawberries

Production, Postharvest Management and Protection

About this book

This book provides unparalleled integration of fundamentals and most advanced management to make this strawberry crop highly remunerative besides enhancing per capita availability of fruit even in the non-traditional regions of the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Strawberries by R M Sharma,Rakesh Yamdagni,A K Dubey,Vikramaditya Pandey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Botany. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | Introduction |

V. Pandey , R. M. Sharma , R. Yamdagni , A. K. Dubey , and Tushar Uttamrao Jadhav

CONTENTS

1.1 Historical Background

1.2 Botany and Taxonomic Status

1.3 Evolution and Distribution

1.4 Crop Improvement and Varietal Wealth

1.5 Growing Environments

1.6 Production Technology

1.7 Protected Cultivation

1.8 Flowering and Fruiting

1.9 Harvesting, Handling and Processing

1.10 Yield

1.11 Economics

1.12 Plant Protection

1.13 Epilogue

References

Excellent features for fruits such as an attractive appearance, unique taste, high nutritive value, year-round availability even when other fresh fruits are scarce in the market, precocious bearing, short duration of cropping, high return per unit area with an attractive profit margin and varied uses as fresh fruit for direct consumption and processing into several value-added products (Sharma et al., 2013; Nile and Park, 2014) have made strawberry a most sought-after fruit crop among growers and consumers alike throughout world. In addition to its food value, multicoloured and double-flowering genotypes of strawberries evolved through intergeneric and interspecific crosses have great ornamental value with good fruit set. Consequently, strawberries have become an integral part of “balcony gardens” – a modern trend in urban horticulture (Olbricht et al., 2014). Their utility in vertical or terrace gardens in metropolitan cities across the world is now a reality and not just imaginary. In addition, the adaptability of strawberries to selective tropical and subtropical climatic regions has made it an ideal choice in crop diversification programmes, especially if used to fill gaps in young fruit orchards of various types.

1.1 Historical Background

Strawberries are believed to have been in cultivation by Romans even before the beginning of the Christian era. A wild species in the genus Fragaria, specifically Fragaria vesca, is said to have been observed growing abundantly throughout the Northern Hemisphere long before the development of present-day cultivated strawberries. In the United States, the cultivation of strawberries started in the early 18th century. Strawberry had been observed growing in different parts of the world, and this heart-shaped fruit of love was mentioned by the Roman poets Virgil and Ovid in the first centuries BC and AD, and in England, gardeners have been cultivating strawberries since the 16th century AD (Boriss et al., 2006). In most other European countries too, strawberries have had been in cultivation from some time in the 18th century. The first documented botanical illustration of a strawberry plant appeared as a figure in herbaries in 1454 and the English word “strawberry” comes from the Anglo-Saxon “streoberie”, and was not spelt in the modern fashion until 1538.

The genus Fragaria was first summarized in the pre-Linnaean literature by C. Bauhin (1623). The authors of the first Cataloguedu Jardin du Roi called it merely “Fraisieretranger”, or foreign strawberry. Robins, who wrote the Catalogue in 1624, thought it to have come from Pannonie, a region lying between the Danube River to the north and the Illyria to the south in Europe, and gave the “foreign strawberry” the botanical name Fragaria major pannonica. In 1629, Parkinson called it the “Bohemia strawberry” or Fragaria major sterilisseubohemica. By the end of the 15th century, the two strawberries cultivated in gardens were the wood strawberry, F. vesca, and the musky strawberry, Fragaria moschata, both characterized by small, distinctly flavoured fruits. In all, the early botanists of the 16th century had named three European species: F. vesca and its subspecies Fragaria vesca semperflorens; F. moschata; and Fragaria viridis, the green strawberry.

1.2 Botany and Taxonomic Status

Earlier, Linnaeus (1738) described the strawberry under only a monotypic genus Fragaria flagellisreptan in Hortus Cliffortianus but later in Species Plantarum (Linneaus, 1753), he described three species including varieties, although several European species earlier not known properly but now known were omitted, and one belonging to Potentilla was included (Staudt, 1962).

Duchesne (1766), in his classic book L’Histoire Naturelle des Fraisiers, which was revised in 1788, quoted the beginning of strawberry cultivation, and he is credited with publishing the best early taxonomic literature on strawberries (Hedrick, 1919; Staudt, 1962). He maintained the strawberry collection at the Royal Botanic Gardens, having living collections documented from various regions and countries of Europe and the Americas. Later on, he distributed samples to Linnaeus in Sweden.

Taxonomically, strawberries belong to Division: Magnoliophyta; Class: Magnoliopsida; Order: Rosales; Family: Rosaceae; Subfamily: Rosoideae; Tribe: Potentilleae; Subtribe: Fragariinae; Genus: Fragaria L. of the Plant Kingdom. The genus Fragaria is a group of low perennial creeping herbs distributed in the wild in the temperate and subtropical regions of world (Anon, 1956), which forms a polyploidy series (Potter et al., 2007), from diploid to octoploid with basic chromosome number x = 7. It has a close taxonomic relative under the genus Potentilla.

Three flower types exist among octoploid species: pistillate, staminate and hermaphrodite or complete. Plants may also be polygamodioecious, with the first few flowers on predominately pistillate plants producing fruits (Hancock and Bringhurst, 1979). Most modern cultivars have only hermaphrodite flowers. The blossoms are composed of many pistils, each with its own style and stigma attached to a receptacle that develops into a fleshy “fruit” after fertilization of pistils. The true fruit are the nutlets (achenes), each containing one seed, which are found on the surface of the receptacle and result from the fertilization and development of the pistils.

Flowers are white (occasionally tinged with pink), having five petals (Fragaria iinumae has 6–8 petals). In some species, male and female flowers are readily distinguished, but in others (e.g., gynodioecious F. vesca subsp. bracteata), the female flowers have anthers, and are very similar to the bisexual flower (Ashmanet al., 2012). The berries are more diverse, and are mostly used to differentiate species and varieties.

The present Fragaria taxonomy (Chapter 4) includes 20 named wild species, three described naturally occurring hybrid species and two commercially important and cultivated hybrid species. The wild species are distributed in the north temperate and Holarctic zones (Staudt, 1989, 1999a, b; Rousseau-Gueutin et al., 2008).

Staudt (1999a, b) has monographed the American and European Fragaria subspecies, besides revising the Asian species (Staudt, 1999a, b, 2003, 2005; Staudt and Dickore, 2001). The general distribution of specific ploidy levels within certain continents is used to infer the history and evolution of Fragaria species (Staudt, 1999a, b) as detailed in Table 1.1.

TABLE 1.1

Ploidy Level in Fragaria and Their Distribution

Ploidy Level in Fragaria and Their Distribution

| Ploidy Level | Distribution |

| 2× (diploid) | Central Asia and Far East except ssp. vesca occur in both Eurasia and America |

| 4× (tetraploid) | East and South East Asia |

| 6× (hexaploid) | Europe |

| 8×(octoploid) | North and South America (only one species is endemic in the Far East to South Kuriles) |

1.3 Evolution and Distribution

In 1712, a French army officer, A.F. Frezier who was returning from Chile saw large fruited strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis) at Concepcion and brought five plants to France. He distributed two plants to the cargo master of the ship, one to the King’s garden in Paris, one to his superior at Brest and only one kept for himself. An interesting fact is that all the plants brought by Frezier from Chile to France were female, which were easily hybridized with other the octoploid species, Fragaria virginiana, to give rise to the present-day large-fruited cultivated strawberry Fragaria × ananassa Duch. So, the present-day cultivated strawberry Fragaria × ananassa Duch. is considered to have been derived from that hybridization.

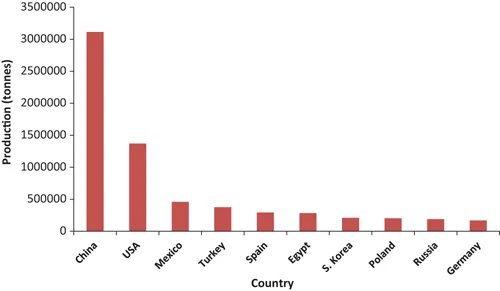

The most significant event in the history of the evolution of the strawberry could be attributed to the introduction of F. virginiana from eastern North America to Europe during the 16th century. Later on, widespread popularity of the strawberry has arisen during the past six decades as strawberry breeders have utilized the available fruit diversity in breeding and genetic improvement programmes to evolve cultivars for specific purposes (Sharma and Yamdagni, 2000). As per estimate (faostat.fao.org), the total world production of strawberry during 2014 was 8,114,373 tonnes. The leading strawberry-producing countries (Figure 1.1) are spread over Asia, North America, Europe and Africa. China (38.36%) is the leading strawberry producer followed by the United States (16.90%), Mexico (5.66%), Turkey (4.60%), Egypt (3.49%), Spain (3.60%), South Korea (2.59%), Poland (2.50%), Russia (2.33%), Germany (2.08%) and Japan (2.02%).

FIGURE 1.1 Top 10 strawberry-producing countries of the world.

In India, strawberry cultivation gained momentum in the late 1960s in Himachal Pradesh and the hills of the then Uttar Pradesh (now Uttarakhand). Presently, strawberry is grown in Maharashtra, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and U...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Editors

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Composition, Quality and Uses

- Chapter 3 Structures and Functions

- Chapter 4 Origin, Taxonomy and Distribution

- Chapter 5 Breeding and Improvement

- Chapter 6 Varieties

- Chapter 7 Tissue Culture

- Chapter 8 Markers and Genetic Mapping

- Chapter 9 Climatic Requirements

- Chapter 10 Soil

- Chapter 11 Propagation

- Chapter 12 Planting

- Chapter 13 Nutrition

- Chapter 14 Water Management

- Chapter 15 Weed Management

- Chapter 16 Mulching

- Chapter 17 Flowering

- Chapter 18 Pollination

- Chapter 19 Fruit Development

- Chapter 20 Use of Plant Bio-regulators

- Chapter 21 Special Cultural Practices

- Chapter 22 Protected Cultivation

- Chapter 23 Soilless Culture

- Chapter 24 Harvesting

- Chapter 25 Yield and Varietal Performance

- Chapter 26 Post-Harvest Handling and Storage

- Chapter 27 Value Addition

- Chapter 28 Physiological Disorders

- Chapter 29 Integrated Disease Management

- Chapter 30 Integrated Insect Pest Management

- Chapter 31 Pesticide Residues

- Chapter 32 Production Economics and Marketing

- Chapter 33 Challenges, Potential and Future Strategies

- Index