eBook - ePub

Compact Cities and Sustainable Urban Development

A Critical Assessment of Policies and Plans from an International Perspective

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Compact Cities and Sustainable Urban Development

A Critical Assessment of Policies and Plans from an International Perspective

About this book

This title was first published in 2000. Encouraging, even requiring, higher density urban development is a major policy in the European Community and of Agenda 21, and a central principle of growth management programmes used by cities around the world. This work takes a critical look at a number of claims made by proponents of this initiative, seeking to answer whether indeed this strategy controls the spread of urban suburbs into open lands, is acceptable to residents, reduces trip lengths and encourages use of public transit, improves efficiency in providing urban infrastructure and services, and results in environmental improvements supporting higher quality of life in cities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Compact Cities and Sustainable Urban Development by Gert de Roo,Donald Miller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction - Compact cities and sustainable development

G. de Roo1 and D. Miller2

1.1 Introduction

There is a widespread belief that compact urban development contributes to sustainability. Sustainability is seen by many as an essential requirement for human survival on planet Earth. Consequently there is a growing public belief that sustainability should become a way of life, guiding the behavior of all of us. Sustainability means that we have to be very cautious concerning what we do, what we want and what we need to create a happy and healthy life for ourselves and our children. Care in the commitment and use of space is one of the most important issues when addressing sustainability.

Space consumption by urban development has become a major concern, not only sn western societies, but throughout the world (Porter, 1997). The reasoning is that compact cities, developed at higher densities and with a mixture of uses, affect sustainability (Crane, 1996; Lowe, 1991). Also the intensity of activities, such as traffic and industry, are seen as major factors influencing sustainability. It is therefore no surprise that land use planning is regarded as a contributing element to sustainability.

The land use planning decisions which we make are known to have long-term effects on the physical environment; effects that often last for many generations. Investments in land development, infrastructure and other capital improvements will impact the physical environment for many years. Consequently, choices concerning these need to be taken thoughtfully. We are increasingly coming to recognize the important relationships between where and how urban development takes place, the effects of land use planning in guiding this, and sustainability (Rees, 1996).

However, there is more. Cities are the principal locations of economic development and social activities, and are therefore highly dynamic in the way in which they are used. As these changes in use occur, these urban dynamics are in conflict with the long lasting effects of land use planning and the long economic life of capital improvements. The location and density of urban functions have to be adapted continuously to changing societal wishes and needs. This development is turning land use planning into a highly complex task. And in a way, it is also subverting the belief that much of contemporary land use planning, and the compact city concept in particular, is a sound instrument contributing to sustainability (Gordon and Richardson, 1997).

Evidence now suggests that the compact city has fewer blessings to offer than were previously expected (Ewing, 1997; Levine, 1998). Instead, urban and environmental planners are becoming aware that there are negative side effects of dense patterns of urban development, such as more acute impacts of pollution and other hazards on neighboring activities. This recognition is the basis for what now is regarded as 'the dilemmas of the compact city'. This book addresses these compact city dilemmas.

Compact Cities and Sustainable Urban Development is the third in a series of books dealing with several aspects of urban development and sustainability. Urban Environmental Planning, the first of these, emphasizes policies, instruments and methods for avoiding and resolving urban environmental problems (Miller and De Roo, 1997). That book was followed by Integrating City Planning and Environmental Improvement, which focuses on practicable strategies for sustainable urban development (Miller and De Roo, 1999). These two books present ways of finding synergy between urban land use planning, environmental issues and sustainability both on a broad strategic level and in more concrete and operational terms. Compact Cities and Sustainable Development extends this inquiry by critically addressing tensions and barriers between urban land use planning, environmental issues and sustainability.

1.2 Sustainable development

'Sustainable development' has become a slogan used world wide in promoting environmentally sound approaches to spatial and economic change. It emphasizes the need for conscientious human behavior to conserve the desirable qualities of the physical environment.

The notion of sustainable development was introduced in 1980 by the IUCN publication, World Conservation Strategy. Nevertheless the concept of sustainability became widely fashionable only after the UN's World Commission on Environment and Development published its report, Our Common Future (WCED, 1987). In the words of the Commission, "...sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (WCED, 1987; 43). This definition requires that the long-term implications of using resources be taken into account, and that intergenerational equity be an important decision rule. The authors of Our Common Future argue that sustainable development is achievable if present generations make necessary investments and if technical developments continue to take place.

While the definition of sustamability used in Our Common Future is anthropocentnc, others see sustainability as synonymous with carrying capacity (Healey and Shaw, 1993). According to Beatley this is the notion "...that a given ecosystem or environment can sustain a certain animal population and that beyond that level overpopulation and species collapse will occur" (1995; 339).

Pearce et al. (1990) define sustainable development as managing resource use in such a maimer as to be able to meet a set of aspirations of society over a considerable period of time. This requires consciousness of the effects of actions, resolve to protect the intrinsic value of the ecosystem, and recognition of time as an important aspect of sustainability. Even after environmentally intrusive emissions have been stopped it takes a while, often a long time, before conditions return to the original state. In the Dutch National Policy Plan the words 'time-lag' and 'friction-time' are used to express this recovery period (VROM, 1989).

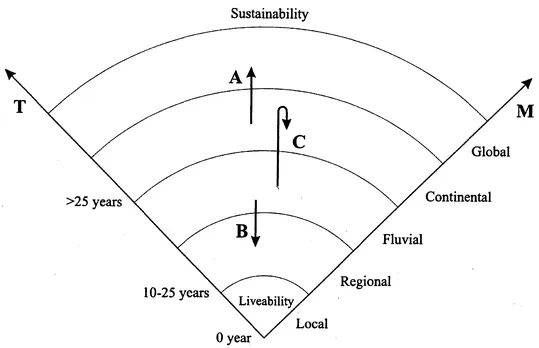

Sustainability involves not only caring about what options are available for future generations; the time dimension portrayed as T in figure 1.1. It also has a spatial dimension, represented by the axis labeled M in this figure. The geographical scale of environmental impacts such as air pollution may be regional, continental and even global. These widespread impacts with long-term implications for effects and resolution are suggested by the arrow A in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Sustainability and livability plotted In Time (T) and Space (M)

1.3 Sustainability versus livability

The environmental impacts of many activities are not limited to the locality in which the activity takes place, but adversely affect sustainability in larger areas and often over prolonged periods of time. Consequently, while we think of livability in terms of conditions at a local scale, wide-ranging environmental impacts even from sources outside of the immediate region can affect local livability (see arrow C in figure 1.1). Furthermore, pollution and other undesirable environmental effects originating outside of the local area are difficult to address and reduce locally (Kirby, 1995).

However, not all negative and unwanted effects are transferred to another area or generation. For example, the impacts of noise from traffic and industrial activities are intensively felt close to the sources. Similarly, the greatest disturbance from odor, vibration, and dust are normally found in the vicinity of the source of emission. Much the same can be said of most of the effects of soil contamination, which usually took place before environmental performance regulations were instituted, and which now restricts the use of these sites. Each of these examples are the result of human actions, are effects which are noticeable locally and immediately, and reduce the livability of people who reside and work nearby.

Beatley (1995) argues that terms such as livability and the quality of life beg for definition and description. He points out that the major purpose of planning is "...creating and supporting humane living environments, livable places, and communities that offer a high quality of life" (1995; 387). This suggests that, while sustainability has spatial implications which may be very large in scale, livability usually focuses on conditions within a locality or urban region (portrayed by arrow B in figure 1.1). Consequently, livability is not synonymous with sustainability, even though these terms are used by some people interchangeably. Strategies for developing compact cities, while they are intended to serve the goal of sustainability, often are met with reservations from intended residents on the grounds that they result in exposure to close-by environmental intrusions such as poor air quality which greatly reduce livability. Much of the public also views high density development as an unattractive residential setting because of noise, lose of visual privacy, lack of greenery and even traffic and parking problems, even while they may support the sustainability principles thought to be served by this sort of urban form (Katz, 1993).

1.4 The compact city as a spatial concept

Rapid decentralization has been a feature of urban growth in most western countries following the Second World War, and even earlier in the United States. This decentralization has taken the form of massive suburbanization in Canada, the United States, Japan and Australia, creating in its extreme form 'the 100 mile city' along major transport routes (Sudjic, 1992). However in Europe, urbanization has tended to spread from urban nuclei. In each case, open rural land is converted to urban uses. These patterns have been a source of concern because of loss of landscape and the costs of providing infrastructure at a vastly increasing spatial scale.

The compact city has been espoused as a counter strategy: to reduce the spread of low density urban development and to preserve the countryside. Prescriptions concerning the form that recentralized, compact urban development should take vary from urban infill and moderately higher densities in existing community centers, to major restructuring of cities (Downs, 1994). In one of the more extreme proposals: "A quarter of a million people would live in a two mile wide, eight level tapering cylinder. In a climate-controlled interior, travel distances between horizontal and vertical destinations would be very low, and energy consumption would be minimized" (Dantzig and Saaty, 1973).

In addition to loss of open countryside to suburban development, adoption of compact city development policies in Europe, starting in the late 1970s, were motivated by the desire to make cities self contained (Elkin et al., 1991). This was seen as a means of avoiding or reversing weakening the functions of the inner city, and of creating low-income ghettos as has often happened in the United States (see Jacobs, 1961, Kunstler, 1993, Smyth, 1996), The 'evil of urban sprawl' (Beatley, 1995; 384) is now a wide spread cause of concern, and has fueled interest not only in more intense use of urban space, but also in a greater mixture of uses in urban space. While these features are characteristics of older cities, which were developed when transport technology required minimizing distances between activities, much of recent growth even of these historic cities has taken the form of low density spread at their edges (Handy, 1992). For example, between 1965 and 1990, while the population of the New York metropolitan area grew by five percent, the developed area of this region expanded by sixty one percent.

Lower density development has increased dependence on the automobile for transportation, and reduced the effectiveness of public transportation. Concern over traffic congestion as well as the environmental impacts and resource costs of using the private automobile, usually by the driver riding alone, is an additional major argument used by advocates for compact urban development (Newman and Kenworthy, 1991). Higher densities and mixed uses, it is reasoned, reduce trip lengths and make public transport an attractive option (Mantell et al., 1990). Some evidence suggests that these effects may be modest. For example, Cervero and Gorham (1995) found that doubling density increased modal shift to public transit by only ten percent. Where, however, development of compact cities does significantly reduce single occupancy vehicle use, this result would contribute to sustainability.

1.5 The compact city as a concept for sustainability

This line of reasoning has led, for example, Elkin et al. (1991; 12) to advocate that the city be of . .a form and scale appropriate to walking, cycling and efficient public transport, and with a compactness that encourages social interaction". This position illustrates the conclusion of Jenks, Burton and Williams (1996), that "...recently, much attention has focussed on the relationship between urban form and sustainability, the suggestion being that the shape and density of cities can have implications for their future. From this debate, strong arguments are emerging that the compact city is the most sustainable form".

The United Nations conference on Environment and Development, held in June 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, has been an important stimulus for sustainable urban development (United Nations, 1992). Local Agenda 21, a major result of this conference, calls for local authorities to work toward sustainability by developing efficient and environmentally friendly systems of public transport and non-motorized trip making, supported in turn by the compact city concept.

Similarly, the European Union has adopted policies instructing national and local governments to pursue sustainable urban development. In the Green Paper on the Urban Environment, the European Commission is especially concerned by the growth in dependency on the car and the use of single occupancy vehicles (CEC, 1990). This development, they note, has resulted in urban traffic congestion, noise and air pollution. They, too, urge mixed use development in existing urban areas, more residential development in the inner cities, and focusing growth within existing urban boundaries (CEC, 1990; 60). As a number of analysts conclude, these guidelines for urban development represent a strong endorsement by the European Commission for the compact city (Breheny and Rookwood, 1993;155 and Hall, Hebbert and Lusser, 1993; 23).

A counterpart response in the United States has been the adoption of urban growth management programs by eleven state legislatures in high growth regions (DeGrove and Miness, 1992). State growth management programs require cities and urban regions to prepare and implement plans which include defined urban growth boundaries, identify and protect critical areas, require that infrastructure be in place before development is permitted, and encourage infill development (Burby and May, 1997; Gale, 1992). Some local plans call for 'urban villages' which are higher density and mixed use development around existing community centers, thus reinforcing the multiple-centered urban form which has become characteristic of U.S. metropolitan areas over the last few decades.

1.6 Compactness versus sust...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction - Compact cities and sustainable development

- Part A: The dilemmas of compact city development

- Part B: Problems in renewing and reusing sites to increase densities

- Part C: Measuring environmental quality perceptions

- Part D: Citizen participation strategies and methods

- Part E: Impacts of automobile dependency in compact cities

- Part F: Strategies for reducing traffic impacts in compact cities