- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Impact of Marine Pollution

About this book

Originally published in 1980, this book by a group of international lawyers and experts from the energy industries suggests ways in which the law may have to change to cope with developments in the oil and nuclear energy industries and the way they impact on marine pollution. Incorporating issues arising on an international and comparative basis, the book discusses the approaches made to marine pollution problems by the UK, EU and USA.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Impact of Marine Pollution by Douglas J. Cusine,John P. Grant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I:

OIL POLLUTION

1 The Legal Framework

Douglas J. Cusine and John P. Grant

1 Introduction

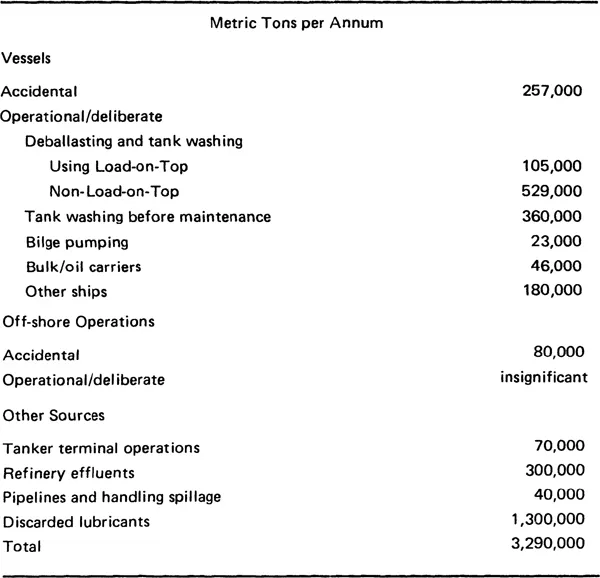

The increasing concern within States about the protection of the environment has been matched, if not overtaken, by international concern about the pollution of the seas, particularly by oil. The estimated amount of oil entering the oceans annually is some 3.3m metric tons, of which 1.5m metric tons comes from ships, 1.7m metric tons from on-shore activities (including a massive 1.3m metric tons of discarded lubricants) and 0.08m metric tons from off-shore exploration and exploitation activities. A more detailed analysis of these figures can be seen from Table 1.1

Table 1: Estimate of Oil Entering the Oceans

Pollution, by its nature, is not readily subject to the normal jurisdictional rules. If the flag State will not act to punish discharges of oil from vessels of its nationality, the competence of States directly affected by the discharge is restricted to the outer limits of territorial waters. Canada, which was convinced of the inadequacy of these jurisdictional rules, enacted the Canadian Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act in 1970,2 purporting to require all vessels in a belt of waters extending up to 100 miles from the Canadian coastline to comply with Canadian regulations governing navigation, safety and the dumping of wastes. This statute, which met with protests from the United States and United Kingdom Governments, appears to go beyond what is permissible by existing international law. It is clear, therefore, that pollution of the sea can best be dealt with through international agreement, setting standards for implementation and enforcement by States.3

It is sometimes appropriate in considering international law and municipal law operating within the same field to deal first with international law (both customary law and conventional law) and then to consider the position in municipal law (both at common law and under statute). This approach is not considered wholly appropriate in issues such as marine pollution. Instead, it is proposed to look at customary international law and then the position at common law in the UK in an attempt to demonstrate the ability or otherwise of these sources/systems/ regimes to provide a solution to the types of legal problem that invariably arise from an incident causing marine pollution. Thereafter, we shall analyse the international agreements concluded to prevent and to mitigate the consequences of any such incident; and we shall analyse the statutes giving effect to those agreements in one country— the UK. To look at the international agreements and the UK statutes separately would be quite inappropriate, as they are interrelated: the international agreements were by and large concluded through an international institution (IMCO) whose headquarters are in London and to whose work the UK has been a consistent and strong contributor; and the UK legislation that will be considered has by and large been passed to implement these agreements. In short, the international agreements and the UK legislation, while emanating from different sources and having different effects, are closely related, and only by considering them together can any reasonable assessment be made of their terms (for the wording frequently differs) and their relative effectiveness.

Adopting that approach, our first question is therefore: does international law provide any rules of law on pollution in the absence of international agreements? Put another way: are there any customary rules of law on pollution, rules deriving their force from the common practice of States?4 To recast the question yet again in a more practical way: are there any rules of international law which could bind those States that are not parties to some or all of the international agreements?

In one famous international arbitration, the Trail Smelter Arbitration,5 there appears the following statement: ‘no State has the right to use or permit the use of its territory in such a manner as to cause injury or damage ... in or to the territory of another or the properties or persons therein.’ This case concerned fumes, including quantities of sulphur dioxide, emitted from a lead and zinc smelter in Trail, British Columbia, which caused damage in the State of Washington. It is open to doubt how wide the ratio of the Trail Smelter Arbitration can be extended. On a narrow construction, it might be applicable to nothing more than damage caused in one State by activities carried out in another State. On a broad construction, it might be applicable to any damage caused to a State or its nationals by a vessel subject to the jurisdiction of another State. It is, of course, only on this latter construction that the case is relevant to the question of pollution of the sea by oil.

Some authorities take the view that the broad construction of the ratio of the Trail Smelter Arbitration is to be preferred.6 This view is supported by the decision of the International Court of Justice in the Corfu Channel Case, where the Court recognised ‘every State’s obligation not to allow knowingly its territory to be used for acts contrary to the rights of other States’;7 by the International Law Commission’s statement in 1956 that ‘States are bound to refrain from any acts which might adversely affect the use of the high seas by nationals of other States’;8 and by some of the provisions of the Geneva Convention on the High Seas of 1958, which resulted from the work of the I.L.C. and which are expressly stated as being ‘generally declaratory of established principles of international law’, requiring the four freedoms of the high seas (navigation, fishing, laying cables and pipelines and overflight) to be exercised subject to other rules of law and to the rights of other States in the high seas, and imposing on all States a general obligation to prevent pollution of the seas.9 Further, it can be argued that a broad construction of the ratio in the Trail Smelter Arbitration is more in accord with the nature of international law, a system that is generally thought to establish, through custom, broad principles of general application, rather than detailed rules to be followed in every particular.

In support of the contention that there is a customary legal regime governing pollution of the seas, reference may be made also to the doctrine of abuse of rights. This doctrine is based on the premiss that a State is in breach of international law if it exercises a right that it has in such a way as to prejudice other States exercising rights they enjoy. It is a well established principle that the high seas are free and open for the use of all States; that it is, in effect, res communis. Yet, each and every State can only exercise the freedoms it has in the high seas, in the words of the Convention on the High Seas, ‘with reasonable regard to the interests of other States in their exercise of the freedom of the high seas’.10

While the doctrine of the abuse of rights has been recognised by the World Court,11 it is still somewhat controversial. Clearly, it can be characterised as a general principle of law, and as such can be a source of international law,12 and it may be the genesis of a rule of customary law, such as the rule enunciated in the Trail Smelter Arbitration.13 However, the operation of the doctrine is not free from difficulty. In the words of one scholar:

[t]here is no legal right, however well established, that could not, in some circumstances, be refused recognition on the ground that it had been abused. The doctrine of abuse of rights is therefore an instrument which . .. must be wielded with studied restraint.14

The assertion that the doctrine falls to be applied in a particular case may be no more than a call for a more exact legal regime, and this may, at one time at least, have been particularly true of the law relating to pollution.

1.1 United Kingdom Common Law

At the municipal level within the UK, there has been only one decision in which the common law on oil pollution has been at issue. In Esso Petroleum Co. Ltd v. Southport Corporation15 the beach at Southport was damaged by oil jettisoned from an oil tanker within territorial waters. A claim for damages alleging nuisance, trespass and negligence was raised by Southport Corporation against the owners of the tanker. The House of Lords took the view that it was unnecessary to consider whether such a claim based on nuisance and trespass was competent, as the oil had been discharged in order to save the lives of the crew. On the question of negligence, it was held that the Corporation had not established the allegations in their pleadings, and the action therefore failed. As a precedent of common law, the case is of limited value.

It would appear that the English principle enunciated in Rylands v. Fletcher,16 and the corresponding Scottish principle, in Kerr v. Earl of Orkney,17 apply only to the escape of dangerous things from land and that their extension to a discharge of oil by a ship either on the high seas or within territorial waters is probably unwarranted.18

However, given the present delimitation of the UK continental shelf for jurisdictional purposes,19 which places the vast majority of the North Sea oilfields appertaining to the UK within the Scottish sector,20 it is apposite to consider the position at common law in Scotland. The decision in Esso Petroleum Co. Ltd v. Southport Corporation is not binding in Scotland. Scots law does not attach the same meaning as English law to the terms ‘nuisance’, ‘trespass’ and ‘negligence’, but instead recognises a general principle that no one is entitled to do anything on his own property which will interfere with the natural rights of others (sic utere tuo ut alienum non laedas). One particular aspect of this principle is nuisance, for which liability in Scots law is strict. While, normally, nuisance is a continuing infringement of another’s rights, there is authority for the view that one incident is sufficient to constitute nuisance,21 and so the discharge of oil which subsequently fouls a beach or otherwise damages another person’s property could in Scots law amount to a nuisance.

That there are rules of customary international law and of common law concerning pollution is clear. What is equally clear is that those rules are too general or too skeletal or too fragmentary to cope with the pollution problems that arise in practice, and these rules have been, and are being, provided with flesh and made more precise by international agreements, and subsequent municipal legislation. There are now in the order of a dozen major international agreements, not all of which are yet in force. Notwithstanding that, howeve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of International Instruments

- List of Abbreviations and Definitions

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I: Oil Pollution

- Part II: Pollution from Sources Other than Oil

- Part III: Comparisons

- Notes on Contributors

- Index