Indian Insects

Diversity and Science

- 450 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Indian Insects

Diversity and Science

About this book

Insects are the most interesting and diverse group of organisms on earth, many of which are useful as pollinators of crops and wild plants while others are useful as natural enemies keeping pestiferous insects in check. It is important to conserve these insects for our survival and for this the diversity of insect species inhabiting the different ecosystems of our country must be known. The cornerstone to studies of any kind of organismal diversity is their taxonomic identity. Even after over two and half centuries of studies, so little is known of the insect wealth of our country. It has contributions from taxonomists who have been studying Indian insects for long, this book offers up to date information on many important groups of Indian insects seeking to fill the lacuna of a long felt need for a comprehensive work on the taxonomy of Indian insects.

Salient features:

- Provides an up-to-date taxonomy of major insect groups of India

- Presents identification keys with illustrations of several important groups of Indian insects

- Gives a new insight into why insects are so abundant

- Addresses fundamental questions in mechanoreception and cross kingdom interactions using insects as model systems

Indian Insects: Diversity and Science is a festschrift to Professor C. A. Viraktamath, an insect taxonomist par excellence. It has been designed to cater to the needs of academicians, researchers and students who wish to identify insects collected from local environments and will be an invaluable aid for those working in the areas of systematics, ecology, behaviour, diversity and the conservation of insects.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

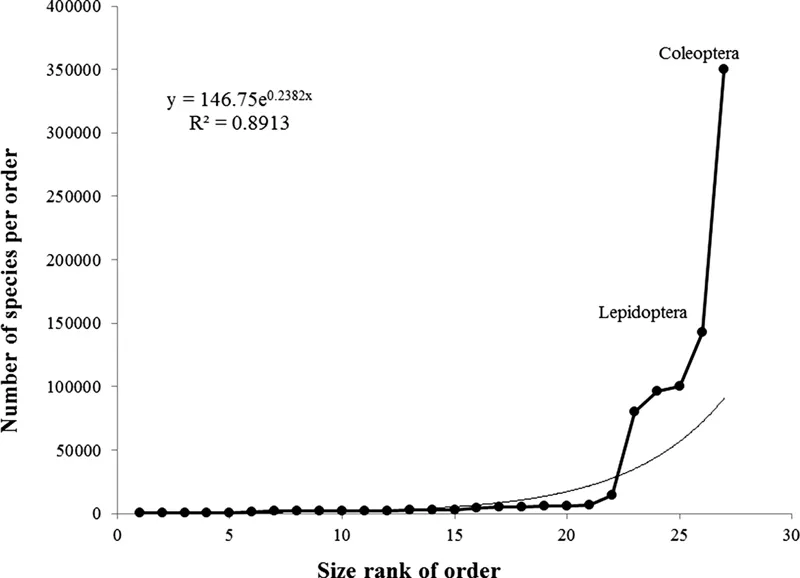

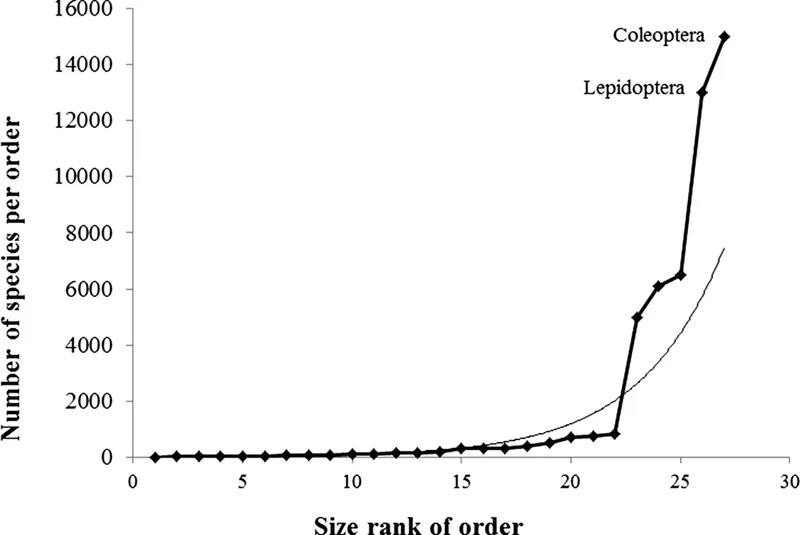

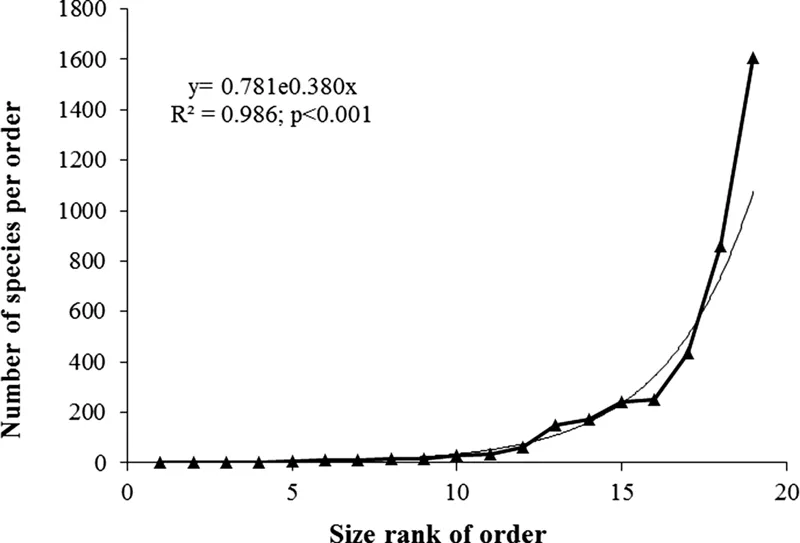

1 | Why Are Insects Abundant? Chance or Design?K. N. Ganeshaiah |

A QUIP: GOD AND THE BEETLES

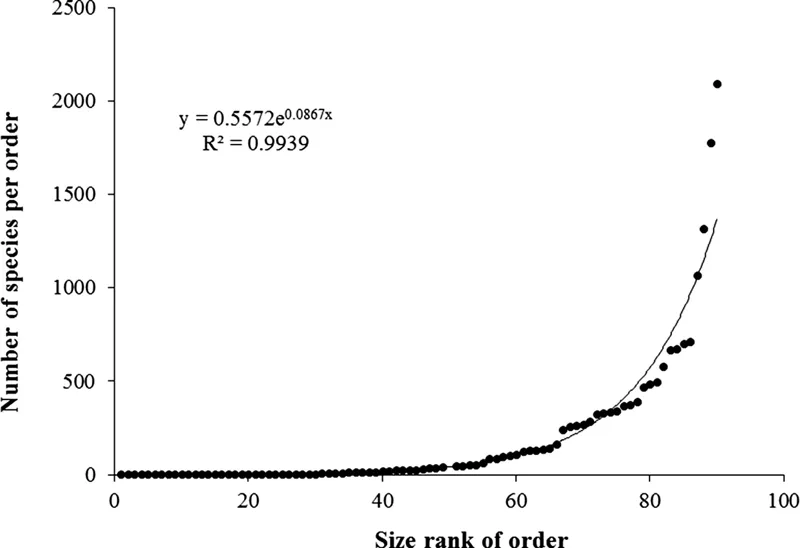

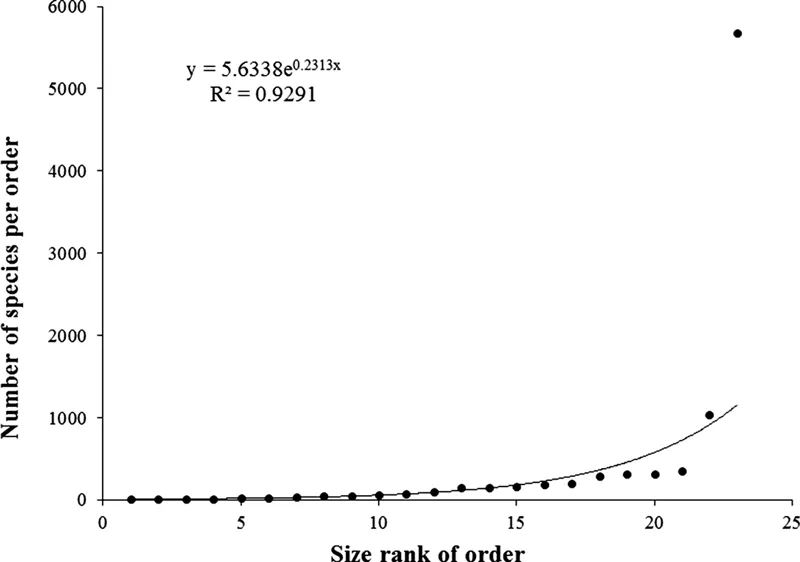

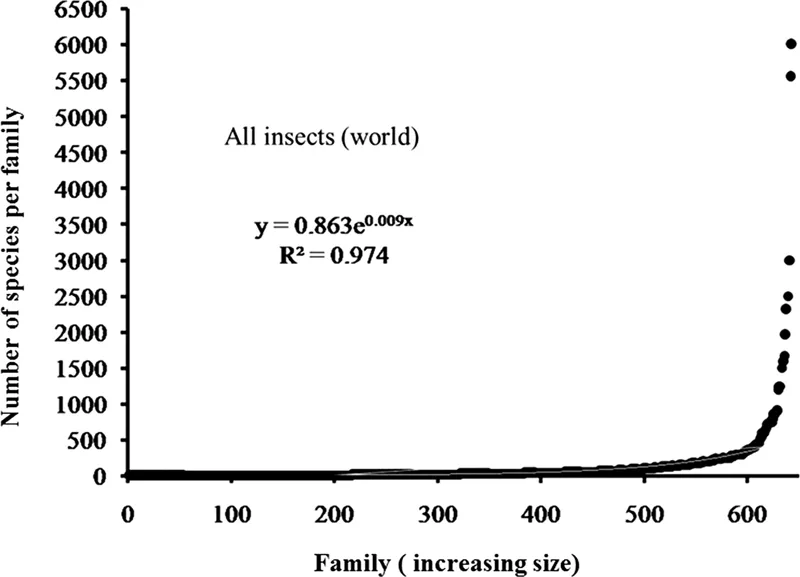

WHY ARE BEETLES SPECIES RICH?

ARE BEETLES UNIQUELY DIVERSE COMPARED TO OTHER GROUPS?

SPECIES RADIATION AS A POSITIVE FEEDBACK PROCESS: A HYPOTHESIS

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Editors

- Chandrashekaraswami Adiveyya Viraktamath: The Prince of Indian Taxonomists

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Why Are Insects Abundant? Chance or Design?

- Chapter 2 Mayflies (Insecta: Ephemeroptera) of India

- Chapter 3 Dragonflies and Damselflies (Insecta: Odonata) of India

- Chapter 4 Stoneflies (Insecta: Plecoptera) of India

- Chapter 5 Taxonomy of Orthoptera with Emphasis on Acrididae

- Chapter 6 Taxonomy and Biodiversity of Soft Scales (Hemiptera: Coccidae)

- Chapter 7 Whiteflies (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) of India

- Chapter 8 Pentatomidae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomoidea) of India

- Chapter 9 Indian Mymaridae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea)

- Chapter 10 Scelionidae and Platygastridae (Hymenoptera: Platygastroidea) of India

- Chapter 11 Bumble Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apinae: Bombini) of India

- Chapter 12 Potter Wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Eumeninae) of India

- Chapter 13 Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae): Their History and Future in Indian Biological Studies

- Chapter 14 Coccinellidae of the Indian Subcontinent

- Chapter 15 Flea Beetles of South India (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Galerucinae: Alticini)

- Chapter 16 Taxonomy, Systematics, and Biology of Indian Butterflies in the 21st Century

- Chapter 17 Taxonomy and Diversity of Indian Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae)

- Chapter 18 Hover-Flies (Diptera: Syrphidae) Recorded from “Dravidia,” or Central and Peninsular India and Sri Lanka: An Annotated Checklist and Bibliography

- Chapter 19 A Comparative Study of Antennal Mechanosensors in Insects

- Chapter 20 Cross-Kingdom Interactions in Natural Microcosms: The Worlds Within Fig Syconia and Ant-Plant Domatia

- Annexure I: Revisions and Reviews of Taxa by Professor C. A. Viraktamath

- Annexure II: New Tribe and Genera Described by Professor C. A. Viraktamath

- Annexure III: New Species Described by Professor C. A. Viraktamath

- Annexure IV: Research Publications of Professor C. A. Viraktamath

- Annexure V: Taxa Named in Honour of Professor C. A. Viraktamath

- Annexure VI: Courses Offered by Professor C. A. Viraktamath

- Annexure VII: Theses Submitted Under the Guidance of Professor C. A. Viraktamath (1980–2019)

- Annexure VIII: Research Projects Operated by Professor C. A. Viraktamath

- Index