![]()

1 Introduction

In the English social welfare system, a distinction has existed for a considerable time between those who believe that recipients of welfare assistance are ‘deserving’ and those who believe they are ‘undeserving’. This was the inheritance embraced by Michael Portillo, then chief secretary to the Treasury, who argued that

This concept of the deserving and undeserving poor is embedded in our social welfare legislation, taking its roots from the old Poor Law (see, for example, Cranston, 1985, p.34 ff). Indeed, the social welfare battleground in the second half of the twentieth century has this as its common thread, although it is expressed slightly differently:

The thesis of this book is the rejection of the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor. That distinction should be regarded as a deliberate obfuscation of the principles of the Thatcher/Major administrations to which this book relates. Those principles have involved reducing welfare assistance to a ‘safety net’. In any event, the debate surrounding the distinction has always been sterile, for it required the creation and propagation of stereotypes and generalizations, none of which had any empirical justification. They were simply based upon prejudice and enabled the ruling classes to characterize as well as categorize the effects of poverty. This concentration on a sharp divide has also enabled the Thatcher/Major administrations to increase the scope of the ‘undeserving’ as part of measures designed to reduce public expenditure. In housing, that reduction since 1979 has been so significant that local authorities became unable to build new accommodation and housing associations (and other similar organizations) find their budgets cut each year. The result of this is that only the most deserving can be successful homelessness applicants, but that the construction of that category does not always require a judgment to be made about the individual. Rather, sometimes external circumstances can define that category. Thus, in Chapter 2, I have argued that we should define this category as the appropriate applicant.

This housing crisis has been manifested in two seemingly contradictory contexts of the homelessness legislation. The first has required a movement towards ‘partnership’ (different words were employed depending upon the context in which it was used) between different agencies, whether they be statutory, voluntary or quasi-public. This policy was always expressed positively and was one of social inclusion. It had a brief vogue in government policy in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Chapters 2-6 argue that the homelessness legislation provided an inadequate structure for ‘partnership’ to occur in the desired way. Furthermore, the homelessness legislation apparently contradicted the approach and philosophy of the new policies. The second context ‘trades in images, archetypes and anxieties, rather than in careful analyses and research findings’ (Garland, 1996, p.461). This process has been partly responsible for the downgrading of responsibilities to the homeless, although the effects of that downgrading are more general. Thus this concerns negative images and is the catalyst of social exclusion – the inappropriate applicant.

The direct parallel is with the discourse of criminology, with which later chapters in this book link. Garland argues that the suggested failure of the state to control crime has led to the rise of ‘a new genre of criminological discourse ... that crime is a normal, commonplace, aspect of modern society’ (ibid., p.450). This has caused a new method of controlling, as opposed to the eradication of, crime to develop which he terms ‘the responsibilization strategy’; that is, responsibility for crime control is more actively located in the private sector, which is to work in partnership with the state agencies.

Hence the recent move towards punitive, penal policies as ‘an act of sovereign might, a performative action which exemplifies what absolute power is all about’ (ibid., p.461). So there is also the creation of a dualist, polarized and ambivalent criminology, which Garland describes in the following terms:

Adapting this terminology, this book argues that precisely the same can be seen to have operated within the context of homelessness and the decision-making processes required by the homelessness legislation. The link between the two is important. There is now a homelessness of the self, on the one hand, represented by current policies covering, for example, community care, children, racial harassment and violence to women. On the other hand, throughout the 1990s, the Conservatives have systematically created a homelessness of the other, represented by specifying particular types of housing demons – squatters, travellers, ‘aggressive’ beggars, asylum seekers and illegal immigrants – and particular types of homelessness demons – single mothers and queue jumpers. The practical application of the policies of ‘selfness’ took place at the same time as ‘otherness’ gained dominance. It was therefore unlikely that the requisite structures, which would have facilitated that practical application, would be put in place.

The rest of this introduction first provides details of the evidence of the state’s failure in the provision of housing, which is essential background information. Second, the argument in Chapters 2-6 – that ‘partnership’ was unlikely to be successful in practice – will be introduced and considered through its theoretical underpinnings. Third, the methodology of the field-work used in those chapters will be outlined. The final section provides an outline of the argument in the subsequent chapters.

The Failure of the State and the State of Failure

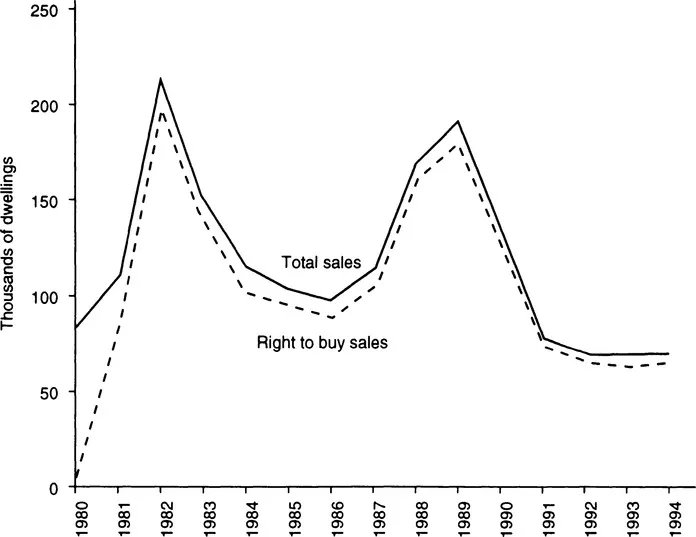

Thatcher’s attack on state housing was based on the following premises: as a form of tenure, it was inefficient, wasteful and costly, discouraged mobility and denied consumer choice (Cole & Furbey, 1994, pp.188-94). As a result, consistently through the 1980s, the government pursued its housing policies first and foremost through providing local authority tenants a right to buy their properties. Subsequently, when interest in the scheme began to wane, the government increased the sweeteners given to tenants in the form of massive reductions in value, depending upon how long the tenant had occupied the property. Larger sweeteners were given to those tenants occupying less desirable properties (flats and maisonettes) although sales of these properties continued to be sluggish. Nevertheless, as Figure 1.1 shows, local authority dwelling sales remained at remarkably consistent levels, despite the operation of external factors affecting other sectors of the property market.

Figure 1.1 Local authority dwelling sales: 1980-94

Source: DoE 1996d

The programme of selling was also enhanced by innovative and diverse methods of ownership creation such as the half buy-half rent and rent-to-mortgage schemes (although take-up of the latter has been negligible). By 1988, with a substantial number of the best properties sold, the government had created so many incentives to move away from local authority tenure and in favour of housing association tenure that a substantial proportion of housing had been sold off en bloc to newly created housing associations.1 Rumours abounded that the Conservatives’ 1997 election manifesto would promise to require local authorities to transfer all their remaining stock to housing associations or the private sector. It would have been had they been elected the natural result of government policy.

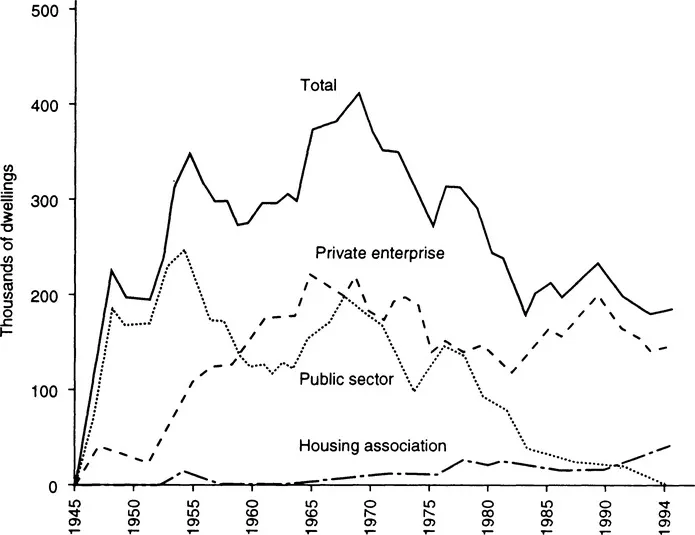

Between the introduction of the ‘right to buy’ legislation in October 1980 and the end of June 1996, the total sales of local authority property were 1-270 million homes. Local authority tenure was therefore reduced from housing 30 per cent of the population to 22 per cent and currently stands at about 20 per cent. The authorities that assisted with the fieldwork conducted for the first part of this book have been similarly affected (for ‘right to buy’ statistics in our study authorities, see Appendix 4; for housebuilding in study authorities, see Appendix 3; for housing tenure in our study authorities, see Appendix 2). During the 1980s, the sale of the state’s housing stock represented 43 per cent of all proceeds of the various privatization campaigns (Forrest & Murie, 1989). At the same time, legislatively imposed accounting practices were employed to restrict the creation of replacement dwellings (Loughlin, 1986, ch. 4; Hills, 1991, chs 6-7). Local authorities built hardly any new dwellings as Figure 1.2 shows.

The major consequences of these developments are twofold. First, local authority tenure has largely become residual because, as the better quality properties have been sold to tenants, generally poorer stock remains which nobody would buy, however great the incentive or sweetener. Second, purchasers of local authority accommodation were generally, although not exclusively, the more affluent working class who were able to afford it. The remaining rump of local authority tenants comprise the most marginalized and excluded who most commonly require state support (Forrest & Murie, 1991, pp.65-85).

Local authority management has also been subjected to similar processes, for authorities are required to be ‘enablers’ (DoE, 1987) or to facilitate the development and propagation of other forms of tenure in their areas. Management has been subjected to the supposed rigours of the private sector by authorities being required to engage in the process of offering it to the private sector through the policy of compulsory competitive tendering. Recent quasi-legislation now requires local authorities to contract out their housing allocations and homelessness services. ‘Tenants’ choice’, a heavily publicized policy after its introduction in Part IV of the Housing Act 1988, enabled local authority tenants to vote to transfer the management of their properties to alternative bodies. Its abolition in the Housing Act 1996 was explained by the then housing minister who said that the policy itself was ‘silly, ineffective, adversarial, lengthy and costly’ (H.C. Standing Committee G, Twenty Sixth Sitting, col. 1041 per David Curry).

Figure 1.2 Dwellings built nationally: 1945-94

Source: DoE 1996d

The systematic destruction of the state’s provision of housing was therefore a lynchpin of Conservative housing policy. However, it left a gaping hole in the provision of low-income housing. The Conservatives preferred to fill that gap through the vehicle of housing associations, which are (largely) non-profit-making organizations. Housing associations are currently funded partly by government and partly through private finance, but are regulated indirectly through the government’s quango, the Housing Corporation, which is also responsible for handing out public money to housing associations. Housing association tenure has only increased slightly (to around 10 per cent). Successive budgets have reduced the level of available grant and so greater reliance has been forced upon the private sector which, in turn, requires greater risk taking (see, for example, Harrison, 1992; Randolph, 1993; Stewart, 1996, ch. 5). If housing associations are unable to pay their interest payments, the ultimate threat is insolvency. The result of this has been that housing associations are unable to ‘take the strain’ of providing the numbers of homes required (on current estimates, anything between 40 000 and 100000 units of accommodation). It has been suggested that the effects of the 1996 budget will be that the number of homes produced over the next year will miss the government’s target ‘by a wide margin’ (Coulter, 4 December 1996).

Reliance has also been placed on reinvigorating the private sector rental market (see, for example, Crook & Kemp, 1996). However, significant problems exist with this tenure. There has been a historic decline in the rental market, for a number of reasons (see Kemp, 1993) which the Conservative’s policies of deregulation and decontrol have only stemmed (Crook & Kemp, 1996). It appears that a further factor responsible for this stemming – recession – had been ignored by the government in the drive to deregulate the market further (Crook & Kemp, 1996). Two crucial repercussions require consideration: first, when the market improves, many of these properties will be sold back to owner-occupation; second, even given the increase in the rental market, many landlords do not wish to rent to those in receipt of housing benefit (Bevan et al., 1995). Thus this market is often too expensive for those with low or no income.

Initial success of owner-occupation has been superseded by its apparent failure, symbolized by the judicial acceptance of a new phrase: ‘negative equity’ (see Palk v. Mortgage Services Funding Ltd [1993] Ch. 330). Mortgage repossessions and negative equity have created a market in themselves. In the 1990s, in a survey of 31 lenders, repossessions leapt to an all-time high of 68 600 in 1992, falling to 45 800 in 1995, and then increasing slightly to 46 290 in 1996 (Ford, 1996, p.24). In addition, more than 211 000 households owed more than six months’ mortgage payments and 85 000 owed more than 12 months’ (ibid., p.26). It is hardly surprising that, apparently, 61 per cent of home owners ‘strongly agree’ that ‘the government should expand council housing’ (Denny & Ryle, 10 December 1996).

The homelessness statistics suggest a deep-rooted crisis. In England in the 1990s, the homelessness statistics have not fallen below 120 000, reaching a peak in 1992 at 142 890. That the numbers of households accepted as homeless appear to have declined from the peak of 1992 unfortunately tells us nothing. As is pointed out in Chapter 2, the definitions of homelessness are related to the availability of accommodation in the area. If there is no accommodation available in the area, it is likely that few people (if any) will be found homeless. In other words, if local authorities find fewer people to be homeless that is a more potent sign of crisis than an increase in numbers of homeless (because in the latter case the assumption is that there will be more available accommodation). Furthermore, each local authority interprets the legislation and collates its homelessness statistics differently. As will become apparent, some local authorities even take an estimate for the purpose of central data collection. So the homelessness statistics only suggest a housing crisis. They can do no more.

Creating ‘the Appropriate Applicant’

Chapters 2 to 6 use the findings of a fieldwork study in 15 local authorities to sketch a context of the implementation of the homelessness legislation as it was in 1993-4 (Housing Act 1985, Part III). This context was the increasing need for homelessness officers to work in partnership or together with other organizations. The thesis running through these chapters is that the homelessness legislation provided an inadequate basis for these relation...