![]()

De-segmenting research in entrepreneurial finance

Douglas J. Cumming and Silvio Vismara

ABSTRACT

Entrepreneurial finance literature is largely segmented. Different streams of the academic literature between entrepreneurship and finance have become segmented for reasons of theoretical tractability and data availability. In this paper, we discuss the origins and the effects of segmentation by source of financing, by data source, by field, and by country under investigation. We provide a number of examples, mainly from studies on Venture Capital, Initial Public Offerings, and Crowdfunding. We conclude with future research directions, with the hope to help de-segmenting research on entrepreneurial finance.

1. Introduction

The increasing importance of entrepreneurial firms as ‘engines’ of economic development has led to enhanced interest in these firms among policy-makers, regulators, and academics. Agency problems, information asymmetries and lack of internal cash flows or collaterals make it difficult for entrepreneurial firms to raise funds. As a result, questions about the role and impact of legal and market infrastructures on the nature and availability of capital for these firms have been central to research in finance and entrepreneurship for some time. Recently, the understanding of how these firms’ financing decisions evolve has attracted considerable interest. However, thus far, the literature has only skimmed the surface in terms of studying some ‘traditional’ sources of finance (e.g. financial bootstrapping) for entrepreneurial firms. Moreover, the emergence of new trends in entrepreneurial finance, such as crowdfunding, has led to new avenues for research grounded in both financial economics and entrepreneurship. Coherently, a few special issues have and are going to be dedicated to the topic, including those edited by Block, Colombo, Cumming, and Vismara for Small Business Economics: an Entrepreneurship Journal, by Bruton, Khavul, Siegel, and Wright for Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, and by Block, Cumming, and Vismara for the Journal of Industrial and Business Economics (Economia e Politica Industriale).

In their call for papers for the special issue on ‘Embracing entrepreneurial funding innovations’ for Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, Cristiano Bellavitis, Igor Filatotchev, Sam Kamuriwo, and Tom Vanacker argue that ‘the entrepreneurial finance literature is largely segmented’. In this paper, we discuss how entrepreneurial finance literature is segmented (1) by source of financing (e.g. public vs private equity, Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) vs equity-based crowdfunding), (2) by data source (e.g., from investors, entrepreneurs), (3) by field of investigation (e.g. Finance, Entrepreneurship, Law), and (4) by country under investigation (e.g. US-based studies are typically appreciated in finance journals). The next four Sections are dedicated to the discussion of the possible origins and effects of each of these four types of segmentation. We then conclude offering future research directions, with the hope to help de-segmenting research on entrepreneurial finance.

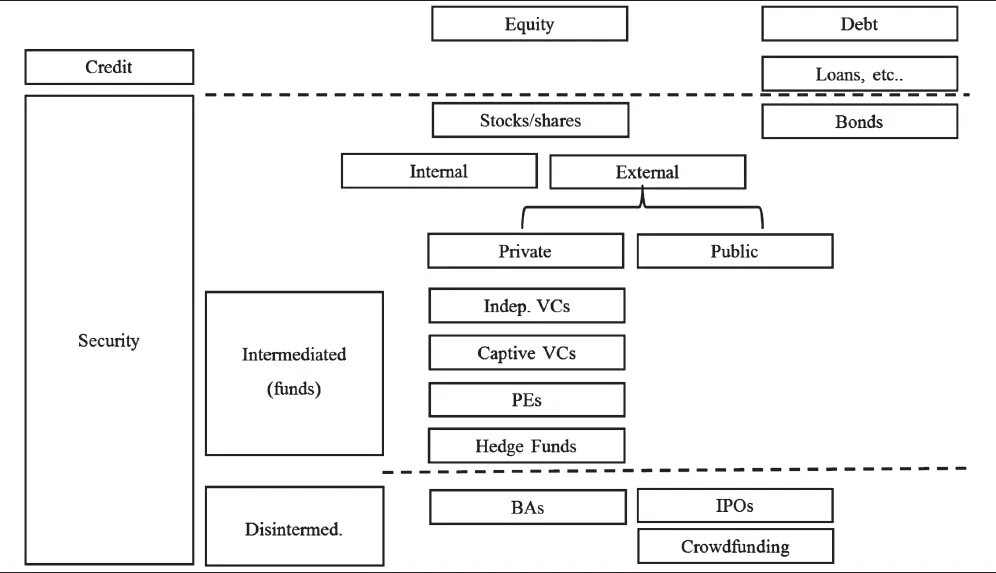

2. Literature segmented by source of financing

Segmented studies treat the source of capital as the only source of financing received by the entrepreneurial firm (Cosh, Cumming, and Hughes 2009). For example, most venture capital (VC) studies do not acknowledge that the firm may have received money from other sources of capital. In general, entrepreneurs raise financing from multiple sources, and it is valuable to study how these sources interact (Hanssens, Deloof, and Vanacker 2015). In this section, we identify some new trends and new financial instruments that might be worth investigating. To do so, we start from the taxonomy of financing means available to entrepreneurial firms. Table 1 graphically summarizes such means of financing.

The first broad distinction is between equity and debt financing. Many discussions have revolved around the unsuitability of debt for early-stage financing (Stiglitz and Weiss 1981). This is mainly due to the fact that debt holders bear the downside risk, but do not share the upside of successful innovation (Berger and Udell 1998). In the absence of sufficient internally generated cash flows, internal equity is often not a viable option for entrepreneurial firms. Our discussion in this Section will be therefore focused on raising equity capital. We are, anyway, aware that this represents a bias in the entrepreneurial finance literature. There is indeed evidence that even early stage entrepreneurial firms rely extensively on bank debt (e.g. Cassia and Vismara 2009b; Robb and Robinson 2014; Hanssens, Deloof, and Vanacker 2016).

Table 1. Means of financing for entrepreneurial firms.

Moreover, there are new forms of debt capital for entrepreneurial firms that are quickly developing, such as mini-bonds. It is not currently clear whether the trading of mini-bonds will take place mostly on traditional regulated markets (e.g. ExtraMOT in Italy) or new crowdfunding platforms (e.g. Crowdcube in the United Kingdom). It is also not clear what will happen when/if interest rates increase, making traditional bank lending less appealing than it currently is. Other forms of debt capital for entrepreneurial firms include credit-based crowdfunding or peer-to-peer (P2P) business lending. These are debt-based transactions between individuals and existing businesses (mostly small firms), with many individual lenders contributing to one loan. The study of these financing mechanisms offers promising ways to contribute to entrepreneurial finance literature.

Crowdfunding involves raising funds from a large pool of backers (crowd) collected online by means of a web platform. These platforms will need to cope with collective-action problems, as crowd-investors have neither the ability nor the incentive, due to small investment sizes, to devote substantial resources to due diligence (Vismara, 2016). How to protect investors in crowdfunding is a challenging topic to address. Many of the traditional research questions in entrepreneurship and finance could be reexamined in the crowdfunding context, with both lending and equity-based platforms. For instance, scholars could exploit this context to derive new insights or study questions that are difficult to address in other contexts.

There are two distinctions in the realm of external equity: namely, private vs. external equity and intermediated vs. disintermediated finance. The first categorization is clear and has been broadly investigated. We believe that the second distinction has gained new momentum, particularly in terms of disintermediated finance, which takes the form of business angels and crowdfunding platforms. Disintermediated finance allows entrepreneurial firms to raise funds directly from individual investors offline (business angels) or online from Internet users (crowdfunding) and seems suitable for financing entrepreneurial firms in their early stages, when firms are not yet attractive for venture capitalists and are not ready for an IPO.

Little is known about the effectiveness of disintermediated entrepreneurial finance in solving the financial constraints of entrepreneurial firms. By easing the manner in which demand for capital meets supply, the development of crowdfunding platforms is expected to improve the efficiency of financial markets (Agrawal, Catalini, and Goldfarb 2015). However, the Internet has long presented the promise of entrepreneurial finance disintermediation, if not democratization. For example, in the 1990s, online auction IPOs were viewed as an alternative to the traditional book-building method of IPO underwriting and an efficient market mechanism to lower costs of going public (Ritter 2013). Unfortunately, the expectations of online auction IPOs were never realized. Only one investment bank, W.R. Hambrecht, has developed a platform for online public offerings, and only 20 American companies, the most notable being Google, have gone public with online auctions (see Jay Ritter’s IPOs Updated Statistics). The last auction IPO was held on 25 May 2007 (Clean Energy Fuels).

Regarding the VC industry, the recent financial crisis has increased the difficulty for entrepreneurial firms to raise seed and early-stage finance, as traditional venture capitalists have become more risk adverse and focused on later-stage investments (Block and Sandner 2009). Many OECD countries have begun implementing policy interventions (Wilson and Silva 2013), such as using governmental venture capital (GVC) funds as a mechanism to address relevant socioeconomic challenges. Besides addressing the financial gap problem, it is expected that these funds will be used to pursue investments that will ultimately yield social payoffs and positive externalities on society as a whole.1 However, the effects of GVC at the systemic level (i.e. crowding in vs. crowding out) and firm level (i.e. selection vs. treatment) have not always been positive, as reviewed in Colombo, Cumming, and Vismara (2016). Furthermore, controversial academic debate has surrounded the rationale and appropriateness of these programs. Assessing the impact of public policy on VC markets seems particularly important in this climate.

3. Literature segmented by data source

We believe that the scarcity of publicly available data on entrepreneurial finance is among the causes of segmentation in the literature. Although some fields of finance research, such as asset pricing, are based on large, publically available data-sets, most entrepreneurial finance papers are instead based on cross-sectional or, more recently, longitudinal data-sets developed with data collected for a specific study. The data-collection process is therefore particularly challenging and delicate for entrepreneurial finance research. For instance, research on entrepreneurial motivations is often based on qualitative studies and surveys, whereas papers on valuation use hand-collected data, such as from IPO prospectuses (e.g. Vismara, Paleari, and Ritter 2012; Khurshed et al. 2014; Paleari, Signori, and Vismara 2014) or analysts’ equity research reports (e.g. Cassia and Vismara 2009a; Vismara, Signori, and Stefano 2015). More broadly, data often come from different sources, such as investors, entrepreneurs, internet, groups or organizations. A growing number of papers is using data from the website crunchbase (e.g. Cumming, Walz, and Werth 2016). Many studies involve empirical testing using data from vendors, such as Thompson SDC or VentureOne. Crowdfunding data, publicly available from platforms, are now frequently used (e.g. Ahlers et al. 2015; Vismara 2016). The availability and easy access to data have surely influenced the recent growth in the number of crowdfunding papers. Of course, many entrepreneurial firms never reach or do not want to reach the public equity stage. Thus, studying only IPOs and crowdfunded firms entails a selection bias.

Occasionally, such as in some bank and VC studies, data-sets are merged to study two sources of capital simultaneously. Other times, small samples may be hand collected, such as for studies investigating issues that cannot be addressed using data-sets from data vendors. For example, as VC contract details are not available from data vendors, papers might use surveys or actual contracts (e.g. Cumming 2008). Similarly, many papers match IPO data, often hand-collected, with merger and acquisition (M&A) data, often from data-sets such as Thomson Onebanker (e.g. Bonardo, Paleari, and Vismara 2010; Meoli, Paleari, and Vismara 2013; Cattaneo, Meoli, and Vismara 2015).

Studies based on data gathered from entrepreneurs are typically based on large-scale surveys, such as the Kauffman Surveys in the US (Robb and Robinson 2014) or the Center for Business Research (CBR) at Cambridge (Cosh, Cumming, and Hughes 2009). What the CBR and Kauffman data-sets both show is that VC is rare, and most entrepreneurs use debt finance. Hence, the focus of research on VC might be disproportionate.

Last, data could come from groups or organizations. These often include data from the supply side, such as business angel groups or various VC associations. From a different perspective, most literature on public intervention has focused on demand-side public interventions, such as technology transfer offices, incubators, accelerators, proof-of-concept centers and other initiatives of network development, as well as matchmaking involving prospective entrepreneurs and investors (Audretsch et al. 2016). Although the diffusion of such types of gap funding schemes has increased in the United States and in Europe over the last decade, we still miss a comprehensive empirical assessment of the nature and output of such programs, as well as policy evaluation exercises adopting rigorous empirical methods. New insights could come from studies using data from technology parks, industry associations, governmental organizations, and statistical agencies.

4. Literature segmented by field of investigation

Although both topics are at the crossroad between economics and management, finance and entrepreneurship are two distinct research areas. This distinction results in a segmented literature with different specificities in the structure and objectives of papers published in finance vs. entrepreneurship journals. Cumming’s (2015) chapter on ‘Publishing in Finance versus Entrepreneurship/Management Journals’ presents some anecdotes and advice about the opportunities and pitfalls that different fields offer to researchers. In this section, we briefly summarize some of the key differences and comment on how to evolve.

Unlike entrepreneurship papers, finance papers typically do not have a verbal theory section. If there is one, this section is generally short and to the point. Similar to economic but different from management papers, formal mathematical models are sometimes discussed in finance papers, typically preceding an empirical analysis. Finance papers often investigate a phenomenon as fully as possible, without necessarily identifying a clear theoretical contribution. By contrast, entrepreneurship papers prefer to focus on longer verbal theory sections with formal, testable hypotheses. While allowing clear identification of the paper’s contribution, this approach can lead to ‘salami publishing’, in which authors inflate the total number of publications by subdividing published output into numerous thin ‘slices’ or ‘least publishable units’ (Martin 2013, 2016). Empirical tests in management papers are often less concerned about the data quality or completeness of robustness checks, as long as the research question is new and interesting. Finance papers, by contrast, are extremely resolute about demonstrating robustness, even when the research question is not terribly new.

Owing to this field segmentation, literature on entrepreneurial finance has evolved through distinct paths, with the same topic often being addressed from multiple perspectives. When different streams of research study the same thing, authors might respond by conveniently ignoring work by other ...