- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Indoor Air Pollution Control

About this book

This is an all new book designed to provide you the practical information and data you need for indoor air pollution control! Presented early in the book is theory as support for the applications that follow; including a synthesized review of the significant literature on controlling air pollution. Practical applications-largely from the author's own experience-deal with 1) How to conduct indoor air quality investigations in both residences and public access buildings, 2) Indoor air quality mitigation practice, and 3) Case histories. This book will be very useful to consultants and other professionals who grapple to solve real world problems. And it will make an excellent textbook for new courses in indoor air quality. Indoor Air Pollution Control will be used for control and prevention of contaminated air in homes, apartment buildings, office buildings (large and small), hospitals, auditoriums, and other public buildings.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Problem Definition

The contamination of indoor air by a variety of toxic and/or hazardous pollutants has in the last decade become increasingly recognized as a serious (or potentially serious) public health problem. Several factors combined to produce this awareness:

- Questions were raised in the late 1970s about the presence of friable asbestos in public schools.

- Numerous complaints were received from owners of urea-formaldehyde foam-insulated houses of odor and acute irritating symptoms.

- Hundreds of outbreaks of illness among occupants of new or recently remodeled offices, schools, and other public access buildings were reported.

- The potential for energy conservation measures to increase levels of indoor contaminants was recognized by governmental authorities who advocated them.

- Homeowners began seeking alternatives (e.g., kerosene heaters and wood-burning stoves) to the use of what they perceived as high-cost central heating systems.

- The environmental nature of allergies and asthma became better understood.

- It became apparent that radon contamination of residences was not just a problem of uranium mill waste tailings and abandoned phosphate strip mines but a problem affecting millions of homes in the United States, Canada, and Northern Europe.

Indoor air pollution is an age-old problem, dating back to prehistoric times when humans came to live in enclosed shelters. It began, no doubt, with the stench of humans themselves. It began, too, when the utility of fire was discovered and brought indoors for cooking and heating. What is new about the problem of indoor air pollution is our emerging awareness of it and the increasing attention given to its various dimensions by research scientists and regulatory authorities. Within this context, indoor air pollution, or indoor air quality, is a “new kid on the block” and, as we have come to learn, a very big kid indeed. In terms of documentable health effects it appears to be enormously more significant than ambient (outdoor) air pollution, a problem for which the implementation of control measures has cost the United States over $200 billion in the past decade.

Indoor/Outdoor Relationships

During alert, warning, and emergency stages of episodes (periods of high ambient air pollution associated with inversions), episode control plans call for air pollution and public health authorities to advise citizens in the affected area to remain indoors, particularly those at special risk —those, for example, who have existing respiratory or cardiovascular disease. This advice is based on the premise that pollutant concentrations will be lower indoors.

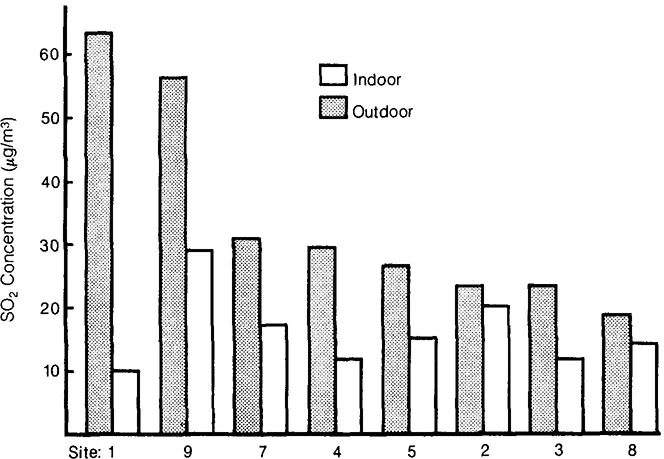

For two of the pollutants of major concern under episode conditions, such advice is in fact appropriate. For sulfur dioxide (S02) and ozone (03), both reactive gases, indoor concentrations are only a fraction of ambient (outdoor) levels. A typical relationship between S02 concentrations indoors and in the ambient environment can be seen in Figure l.l.1 Indoor/outdoor ratios of 0.3-0.5 are typical for areas where ambient levels of S02 are moderate to high. Indoor/outdoor ratios (0.7-0.9) are larger and approach unity when ambient S02 levels are low.2 With few exceptions the predominant source of S02 indoors is infiltration through the building envelope from the ambient environment. An exception to this is households using kerosene heaters with high-sulfur (around 0.30%) fuel. Indoor/outdoor ratios of 03 in houses (0.1-0.2) are substantially lower than unity, indicating that 03 reacts with components of the building envelope or is scavenged by other indoor contaminants.3 In mechanically ventilated buildings indoor/outdoor ratios are on the order of 0.6-0.7.4 Of particular note in the former regard are studies conducted by the author that demonstrate that formaldehyde at levels common to residences rapidly scavenges 03 indoors.5 The ambient environment is in most instances the primary source of 03 indoors. Ozone, however, may be elevated above background levels by emissions from electronic air cleaners, ion generators, and photocopy machines.

Indoor concentrations of combustion-generated contaminants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO), and respirable particles (RSP) have widely varying indoor/outdoor ratios. This variation is due in good measure to the fact that both indoor and outdoor environments can contribute (under varied circumstances) to indoor levels. For nitrogen dioxide (N02), a relatively reactive gas, indoor/outdoor ratios of less than or near unity are typical of residences that have no indoor sources.6 In residences with gas cooking stoves and/or unvented gas or kerosene heaters, indoor NOa levels often exceed those in the ambient environment. Because of its low reactivity, indoor/outdoor ratios of CO in the absence of indoor sources typically approach unity.7 Under episode conditions, CO levels in the indoor environment may not differ from ambient levels. Ratios above unity are associated with the use of gas cooking stoves and ovens, unvented gas and kerosene space heaters, and flue gas spillage.6 A broad range of indoor/outdoor ratios of respirable particles has been reported.8,9 In general, however, RSP levels are considerably higher indoors than they are in the ambient environment. The primary reason for this is tobacco smoking, which is the single most significant contributor to indoor RSP levels.

Figure 1.1 SO2 concentrations in both indoor and outdoor environments at eight monitoring locations in St. Louis, Missouri. 1

Organic compounds, here described as formaldehyde, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and pesticides, often occur indoors at concentrations that exceed ambient levels by several fold or, in the case of formaldehyde, one to two orders of magnitude. Because of the widespread use of organic solvents in building materials, paints, adhesives, and furnishings, indoor nonmethane hydrocarbon levels have been seen to exceed ambient levels by 1.5-1.9 times.9 Concentrations of specific VOCs may exceed ambient levels by a factor of two or more and by as much as a factor of 10.10,11 Because of pesticide use indoors or under the building substructure, levels of such pesticides as chlordane, heptachlor, and chlorpyrifos are often several orders of magnitude higher indoors.12

Radon is ubiquitous in the ambient environment. With the exception of high-ventilation conditions, when indoor/outdoor ratios should approach unity, indoor/outdoor ratios of radon tend to be high to very high. Indoor/ outdoor ratios may vary from as low as 2-3 to a high of 1000 or more.1314 What is unique about radon is that the predominant source is exterior to the building envelope.

Indoor/outdoor ratios of biogenic particles such as mold and bacteria can vary significantly depending on the prevalence of indoor and outdoor sources and the season of the year. In the midwest, mold levels are significantly higher outdoors during the summer months, with correspondingly low indoor/ outdoor ratios. Under winter conditions, indoor/outdoor ratios may be considerably above unity, depending on whether significant internal sources exist and whether snow cover is present.15 Dust mite antigen has no outdoor source.

Differences in indoor/outdoor ratios have special relevance to controlling indoor contamination. If the indoor/outdoor ratio is below 1, the effect of applying general ventilation for contaminant control is increased indoor concentrations of those particular contaminants, notably S02 and 03 and, in summer months, mold spores. On the other hand, when indoor/outdoor ratios are high, considerably exceeding 1, the use of general ventilation for contaminant control would be particularly appropriate. This would be applicable to combustion-generated contaminants, formaldehyde, and radon.

Personal Pollution Exposures

As seen in the previous section, indoor concentrations of specific contaminants may be significantly higher indoors than in the ambient environment. This fact becomes more important when coupled with a consideration of exposure or potential exposure duration. Studies of human activity indicate that, on the average, we spend approximately 22 hr/day indoors, about 16 in our homes.16 We receive most of our personal pollution exposure indoors. Such exposures, for the general population, are probably of more public health importance than exposures to ambient air.

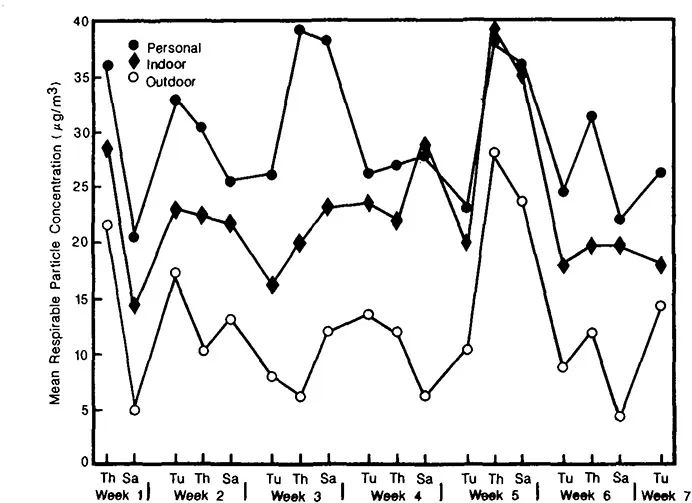

Studies comparing ambient, indoor, and total personal exposures to RSPs have been reported for residents of Topeka, Kansas.17 As can be seen from Figure 1.2, indoor exposures were higher than ambient exposures, with highest values reported for 24-hr total personal exposures.

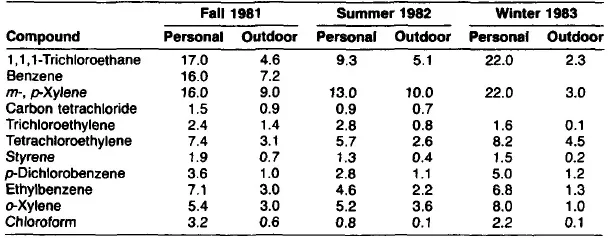

One of the most significant efforts to characterize personal air pollution exposures has been carried on by Wallace et al. under the EPA Total Exposure Assessment Methodology (TEAM) study between 1979 and 1986.1011 Twenty VOCs were measured in personal air, outdoor air, drinking water, and breath of approximately 400 residents of the cities of Bayonne and Elizabeth, New Jersey, Greensboro, North Carolina, and Devil’s Lake, North Dakota. The Bayonne/Elizabeth area is notable for its concentration of chemical plants and refineries. Median concentrations of 11 VOCs are summarized for personal and outdoor air samples in Table 1.1 for Bayonne/Elizabeth residents. In all cases, personal concentrations and exposures exceeded those in outdoor air, usually by a factor of two or more, and sometimes by an order of magnitude. High correlations were observed for breath VOC concentrations and the previous 12-hr air exposure. Correlations between breath and outdoor air concentrations were seldom significant.

Figure 1.2 Indoor, outdoor, and total personal exposure to respirable particles in Topeka, Kansas residents.17

Table 1-1 Weighted Median VOC Concentrations (μg/m3) in Personal and Outdoor Air Samples10

Sick Building Syndrome

The appellation “sick building syndrome” is applied to occurrences of a variety of illness symptoms reported by occupants of large office and other public access buildings. This problem has also been called “building-related illness” and “tight building syndrome.” In problem buildings, there are an unusually high number of individuals (in some cases > 30% of the building population) who complain of symptoms of a nonspecific nature, including headaches, unusual fatigue, eye, nose, and throat irritation, and shortness of breath. A more specific symptom constellation (fever, headache, myalgia) is associated with building-related cases of hypersensitivity pneumonitis and Legionnaires’ disease.

The characterization of building-related health complaints as being due to a sick building suggests that some aspect of the building structure (i.e., the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning [HVAC] system, furnishings, equipment, or a tight thermal envelope) is responsible. The term “tight building syndrome,” once commonly used, implied that the indoor air quality and occupant illness problems were due to energy-conservi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- 1. Problem Definition

- 2. Source Control-Inorganic Contaminants

- 3. Source Control–organic contaminants

- 4. Source Control-Biogenic Particles

- 5. Ventilation For Contaminant Control

- 6. Air Cleaning

- 7. Policy And Regulatory Considerations

- 8. Air Quality Diagnostics

- 9. Mitigation Practice

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Indoor Air Pollution Control by Thad Godish in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.