![]()

1 Introduction

Anti-museum – imagining the unthinkable

This book opens up a new line of enquiry into a leading edge of experimentation and innovation in museum design and practice that was championed by anti-museums. As the name suggests, anti-museums deliberately opposed and reversed the founding principles and aims of what Bennett (1995) calls ‘the modern museum’, and, in most cases they are anti-museums of art. The book will establish their origins, what they do and why, what they have in common (and yet why they are also so diverse), and what impact they have had on visitation, museology and the development of art and art publics.

These ‘outsider institutions’ have been steadily growing in number and reputation since the 1940s, though such are the myriad ways in which convention can be opposed that they never formed a stable binary opposite, or a ‘successor to’, the modern museum in any formal, or collective sense. Nor did they wish to, standardisation was one of the things they opposed. Certainly, no attempt was made to form a new museological movement or art movement. Their strength is expressed instead through their individuality, through their flexibility and capacity to respond intimately to the art worlds around them – which are always particular and ecological (if not exclusively ‘local’) – and through a studied avoidance of collective manifestos, credos, directives or external control. They were almost all experimental, artist-, rather than art history-focussed and interested in developing active new roles in the production and development of art, in its curation and exhibition and more appropriate forms of dissemination to wider audiences. They had pedagogical ambitions but avoided didacticism. After a consideration of their conceptual and historical evolution in this chapter, the book will focus on six detailed case studies of anti-museums in the USA, Europe and Australia.

To many people, the idea of opposing museums, let alone building anything called an anti-museum, might seem absurd: such is the respect accorded them as centres of learning, and such is the fondness with which they are recalled from childhood visits and pleasurable associations with leisure, holidays and tourism. Art museums and galleries are treasured pillars of modern civilisation; they are woven into the fabric of contemporary life and we are currently in the middle of a renewed museum building phase globally. Much hope is pinned to their capacity to catalyse cultural and economic regeneration and most, if not all, of this growth is in the conventional public museum sector. It is true they are loved, but they loved most by a minority dominated by sections of the educated elite. Indifference or ambivalence to them is prevalent in other social groups (Prior 2002; Green 2018; Franklin and Papastergiadis 2017).

It is rare to find more than a quarter of the adult population in any nation having visited an art museum in the previous 12 months. While rates for children are higher, at around 40 per cent, this is largely the result of art museum-going in school curricula. Art museum-going as a life-long pursuit, however, is largely confined to sections of the tertiary educated middle classes, and given that art museums were widely founded in the nineteenth century precisely to encourage everyone to enjoy the benefits of art, and not just the social elite (who collected art and displayed it in their homes), the modern art museum project might be judged a failure on its own terms. These were among the reasons why art critic John Berger was very far from impressed by them. In 1969, he also wrote that art museums were ‘inadequate and outdated’; their curators were ‘patronising, snobbish and lazy’. Further, Berger fumed about a view, common within art museum circles, that the pleasure of art derived from ‘well-formed taste’ and that ‘appreciation’ derived from ‘connoisseurship’. For Berger, both views were ‘mired in eighteenth century thinking’, just as their treatment of the working class as ‘passive [and] made to feel like paupers receiving charity and instruction’, belonged to the nineteenth century (Berger 2018, pp. 171–172; see also Leahy 2010, pp. 162–163).

Views such as these were common enough around the mid-twentieth century, and they prompted a new wave of frustration with the conventional art museum, that emerged especially within the contemporary art movements of the 1950s and 1960s. These were aided and abetted by the alternative society movements, civil rights and liberation politics of the post-war period. Under the pressure to rebuild, democratise and modernise, there were renewed calls for art to be more diverse, contemporary and future-facing. The Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, founded in 1947, was a pathbreaker in this respect. While it deliberately decided not to be a museum, it went further than this by organising its programme in ways that actively opposed the culture of art museums. Critical reviews of its early years jubilantly described it as an anti-museum (e.g. Cranfield 2014). Also from the late 1940s, a circle of Paris-based artists around Jean Dubuffet became disaffected with the art world and the art museum at its centre, arguing that it encouraged a narrow and repetitive elite of ‘anointed’ artists and ignored other, more creative artists from being recognised or seen.

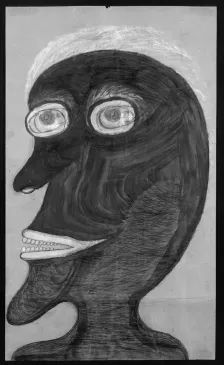

Figure 1.1 Heinrich Anton Müller, untitled, 1925–1927

Source: Courtesy Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

They began to collect art produced outside the canon and experimented with alternative spaces that would show it. In America, as we shall see, anti-museum thinking was also deeply entrenched and gave rise to a proliferation of other forms. By the 1970s these initial impulses began to drive many artists, alongside similarly disaffected curator and collector allies, to find various ways of opposing conventional museology within, as well as beyond a museum building of some kind.

These are the main subject of this book.

Anti-museums were not the only museological change in the second half of the twentieth century. Change accelerated through the 1970s and 1980s when new forms of visitor experience and curatorial practice emerged within the conventional public museum sector in response to new demands to widen attendance, improve engagement, adopt new technologies and commercialise. In the emerging heritage museums, there was a shift away from the dominant culture’s view of history to one shaped by popular culture, oral history, labour history and the everyday. Through negotiation with culturally diverse groups, the heritage museum became a less mediated experience and a more democratic space, converging with, rather than standing apart from, the communities they served (Witcomb 2003; Macdonald 2008). As a result, they thrived and their museum publics expanded. The same cannot be said for art museums.

For Radywyl et al. (2011), the ‘new museology’ produced little change beyond ‘heightened participation’ in most public art museums, and for the most part they remained steadfastly attached to a conventional curatorial offer, structured around academic art history and an improving stance/emphasis on ‘educative leisure’ (Prior 2002; Hanquinet & Savage 2012; Green 2018). In a period characterised by the rise and rise of contemporary art, this inevitably produced a tension with living artists, for whom the art history of their work was a lot less relevant than its subject matter and its intended social impact. Many prominent contemporary artists wanted to raise consciousness and effect social and political change through their work, yet frustratingly, the quietened, reverential gallery spaces and art historical emphasis side tracked visitors into anthology, taxonomy and chronology (Collings 2001; Judd 2016; Green 2018). Fine and important for researchers of art history, but were museums founded primarily for art history research or for the formation of broader art publics? The answer may be both, but arguably only the former thrived in the modern art museum.

Initially, a growing army of young, less prominent contemporary and outsider artists were ignored and left unseen by mainstream art museums. Living artists whether recognised or not, could not be ignored or wrapped up in history in the same way that dead artists had been, and they began to frame new types of alliances with a new generation of activist curators and collectors who often shared their frustrations. The ICA in London was founded by a group of intellectuals, artists and collectors (Cranfield 2008) and they were going to forge something other than an art museum in the conventional sense: ‘an adult play centre, a workshop where work is a joy, a source of vitality and daring experiment’ (Cranfield 2014). Anti-museums were typically founded by new mixes of enthusiast, including amateur collectors in league with artists.

What is an anti-museum?

How then, can a museum be both a museum and against museums? It seems impossible until it is appreciated how the modern museum has largely conformed to a very narrow set of aims, conventions and exhibitionary strategies, and that the aims of most anti-museums are often deliberately and diametrically opposed to them in some, or several, important respects (Berger 2018; Green 2018; Collings 2001). The anti-museum concept begins to make sense when one appreciates that modern museums came into being in the first place as an ‘approved’ and improving form of educative leisure, and as a form of cultural governance and politics at a time in the nineteenth century when northern Europe’s lively and ubiquitous popular culture was being marginalised, discouraged, legislated against, emasculated or banished (Storch 1982; Reid 1982; Daunton 1983; Thompson 1992; Bennett 1995). Carnival had been popular in every village and town across Europe, but its enthusiastic patronage by the aristocracy waned after the French Revolution and their new-found fear of large crowds on city streets. Carnival was left exposed to the rising power of its long-time opponents, the protestant industrialists. In the remarkably short period between 1830 and 1900, carnival was banished almost everywhere, except southern Europe. Just how embedded and extensive art was in the popular cultural realm of carnival before then can be immediately grasped by the profoundly musical nature of London’s streets in the mid-nineteenth century (Simpson 2015), by the depth of visual art, theatricality and comedy in carnival and by the constant reworking of traditional forms of expression addressed to contemporary political issues (Brewer 1979; Bristol 1983; Bruner 2005), all of it taking place in the public realm, and much of it constituting what Adorno (1999) meant by a public sphere. For Bakhtin (1984), here was the ‘borderline between art and life’, and it was produced by a community as a whole, mostly as free expression by individuals and local organisations.

In place of what protestant leaders considered the morally dubious, alcohol fuelled and wild antics of carnival – a period of festivities that reigned across a ‘festive half-year’, from Christmas to midsummer – a new raft of sober-minded, improving leisures were funded and built by Protestant captains of industry, and high on their list was the founding of museums, libraries and art galleries (Roud 2008; Collinson 2016; Franklin 2019). The link between the community and its expressive voice in art was thereby lost in the modern museum. Only the art by recognised and ‘approved’ academic artists was exhibited and only exceptionally would local artists be included; it was collected, curated and exhibited in order to narrate a linear and representative history tracing a developmental path of gradual improvement to the present day, in ways that validated the present and incumbent power; and its purpose was to impart an understanding of the individual artists as they were formed by, and contributed to this historical narrative of ‘progress’ (Bennett 1995). Chronology, taxonomy and didacticism were among its key organising principles and art history was the object of instruction and main purpose of the museum, apart from collection and conservation. The modern art gallery avoided the subjects of art and rendered less vibrant (or urgent) the expectation that art would explore how we might live better lives (Martin 2013; Adorno 1999; O’Connor 2010). As we have seen, almost all of its characteristics, and certainly its aims, have come in for significant criticism over a long period, especially from the artists, curators and collectors in the contemporary art period, so that the wonder is not that there are anti-museums, but why there are so few. The origins and history of these objections are described in the next section.

Origins

The anti-museum concept was conceived and in circulation from around the late eighteenth century. Initially, critics such as Quatremère de Quincy aimed to liberate the objects and artworks from the museum-as-mausoleum – from the way it disconnected them from their origins, contexts and their social life beyond the museum walls (Sherman 1994). At a later point, other critics wished to liberate those subject to its discipline, agency and authority (Maleuvre 1999), especially from the way museum collections were used as forms of memory to divine value, direct, and govern. This criticism focussed variously on the museum as a source of redemptive memory and refuge that stunted progress, or as a place of authoritative retrieval for the modern West’s mythic/egoistic sense of its origins and superiority, or, as its privileged medium for reflection on the human condition (Maleuvre 1999; Butler 2016; Cleary 2006). As such, the anti-museum was proposed as an alternative to both the historic Alexandrina museum paradigm as well as the modern museum itself (Butler 2016; Sherman 1994).

The anti-museum thesis was advanced most radically as a critique of the exhibition of art in museums, as it gathered together concerns, from Quatremère de Quincy to Nietzsche, about the way art objects were thereby disconnected from contexts that give them meaning; from the complex relationships that art works always sustain with life outside the museum (which for some is their destiny), and from their potential for transformative, emotional energy and excitement (Sherman 1994; Huyssen 1986, p. 173). For the Futurists, an early twentieth century art movement with beginnings in Italy, museums were less a valued repository/resource of history than a distraction from the making of history. These were not minor quibbles. The anti-museum critique was vociferously opposed to museums as significant and momentous institutions of power and domination that negates rather than propagates art. They were to be burned and replaced by exhibitionary platforms (especially theatre and performance) where art might be reunited with life, a view recognising that the birth of the modern museum was directly connected with the killing of carnival and the West’s rich popular culture (Bennett 1995; Bakhtin 1984; Marinetti 1909, pp. 189–190).

For some, the term anti-museum is an ill-defined genealogy of entities, variously considered ambiguous, contradictory or impossible to realise. Indeed, as Michaela Giebelhausen (2003) has shown, there are examples of the anti-museum thesis succeeding in the deliberate refusal to build national museums, a case in point being Brasilia which was subject to a thoroughgoing modernist design process. So, the anti-museum also has a life as an absence, and this is emphasised by a number of protest installations over the years from the USA to Germany and Japan (see Copeland & Balthazar 2017 for a compendium of examples), many taking the form of a permanently locked gallery.

More commonly, anti-museum sentiments were acted on by artists and took the form of new exhibitionary platforms, in new spaces and with new narratives (Lorente 2011; Smith 2012). Western contemporary artists had long been sources of criticism of public art museums, many setting up their own not-for-profit artspaces in conjunction with alternative/independent curators and private foundations such as Dia Foundation in the USA.

The modern museum’s emphasis on art history was singularly problematic for the deadening, temporally dissociating exhibition of contemporary art, and many artists felt that their work was not best served by the contemplative, reverential, art historical and corporate cultures of the modern art gallery (as pioneered by MoMA [the Museum of Modern Art, New York) – especially in its ubiquitous white cube style of exhibition where any distractions from the art itself, emotional and otherwise, were removed or discouraged (Duncan & Wallach 1978; Lorente 2011; Maak et al. 2011). Characteristically, contemporary artists want to stimulate strong emotional responses from their publics and to focus attention on the subjects and social/political objects of their art, and thus they grew increasingly frustrated. Such sentiments prompted a move from reason/instruction to emotions/experience, especially in the not-for-profit art spaces and foundations they created (Foster 2015; Krauss 1990; Serota 2000; Smith 2012).

Activism

In the late 1960s, Donald Judd and others developed forms of ‘anti-curation’ and ‘anti-museum’. For example, they moved single-artist sculptural exhibitions into spaces where the subjects of their art and its political and emotional impacts might be heightened (Goldberg 1980, p. 369; Lorente 2011). Judd himself moved away from the cultural centre and precinct to a high desert location at Marfa, Texas, the required journey purposely adding aspects of pilgrimage into the experience (see also Barush 2016). Others used theatrical devices, musical platforms or nightclub metaphors (e.g. PS1, New York). Judd never gave up his total opposition to the mo...