![]()

1 Veronica in Legend and Literature

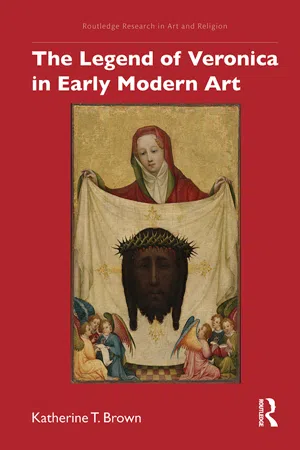

Veronica is usually depicted in Early Modern European works of art as a youthful woman who holds a cloth with an image of Christ’s visage, as for example in Saint Veronica with the Sudarium by the Master of Saint Veronica (Cologne, fl. 1400–1420), datable c. 1420, in The National Gallery, London (Plate 1).1 The character of Veronica, who symbolizes the “true image” relic that she holds, developed from legends originating in the fourth century, a period in the West marked by a rise in reverence for early Christian saints in general.2 Although colloquially called a saint, Veronica was neither listed in the Martyrologium Hieronymianum,3 a fifth-century canon of Christian martyrs pseudo-epigraphically attributed to Saint Jerome, nor was she formally canonized. Folklore about Veronica was augmented during the early medieval period by chronicles of pilgrims to the Holy Land from the fourth century forward. By the fourteenth century, both Veronica as a character and the veronica as a relic had secured recognizable places in the literature and popular culture of Western Europe with mentions by Dante, Petrarch, and Chaucer, as well as chroniclers of Church history.

Veronica is largely considered an apocryphal figure who continues to be celebrated as a patroness of photographers and laundry-workers (because her attribute was a verisimilitude on cloth), despite the fact that Charles Borromeo (1538–1584), Archbishop of Milan during the Counter Reformation, dismissed the Office of Veronica in the Milan Missal, where once it had been included.4 Traditionally, Veronica’s feast day has been celebrated on July 12, a date with origins in the Acta Sanctorum (Acts of the Saints), a hagiography organized by feast day, begun by Heribert Rosweyde (1569–1629) and finished by Jean Bolland (1596–1665), both Flemish Jesuits.5 Their 68-volume work, edited by the Society of Bollandists, describes the lives of 6,200 saints, with Veronica among them.6

Tracing the origins and peripatetic route of the Veronica legend is inherently difficult but possible.7 Many of the stories about her in the Middle Ages, from the eighth century forward, were embellishments on preceding ones with changes in plot details or new endings. Combinations of disparate stories about her and regional variations developed as the legend spread throughout Italy, France, Germany, and England. Foundational to understanding the eventual character of Veronica was an unnamed woman who was living in Jerusalem during the first century. According to Eusebius of Caesarea (260/265–339/340), in his Historia Ecclesiastica (c. 313–324), the woman originated from Caesarea Philippi, a Roman city in the Golan Heights.8 Alternatively, she may have originated from Tyre, Lebanon.9 This anonymous woman, also called the Haemorrhoissa, was believed to have been healed from a long-term illness by touching the fringes or hem of Christ’s cloak as he walked through a crowd, as recounted in Matthew 9:18–26:

While he was saying these things to them, suddenly a leader of the synagogue came in and knelt before him, saying, “My daughter has just died; but come and lay your hand on her, and she will live.” And Jesus got up and followed him, with his disciples. Then suddenly a woman who had been suffering from hemorrhages for twelve years came up behind him and touched the fringe of his cloak, for she said to herself, “If I only touch his cloak, I will be made well.” Jesus turned, and seeing her he said, “Take heart, daughter; your faith has made you well.” And instantly the woman was made well. When Jesus came to the leader’s house and saw the flute players and the crowd making a commotion, he said, “Go away; for the girl is not dead but sleeping.” And they laughed at him. But when the crowd had been put outside, he went in and took her by the hand, and the girl got up. And the report of this spread throughout the district.10

Synoptic accounts in Mark 5:25–3411 and Luke 8:43–4812 vary only slightly. To summarize the story, which occurs within a series of witness accounts of Christ’s miracles, the woman had been bleeding for twelve years. Although she had consulted many physicians, depleting her resources, none had been able to cure her. In fact, she had become worse. Because she had heard of Jesus’s ability to heal, she reached out for him as he passed in a crowded space. When Jesus felt that someone had touched his clothes, he asked who it was. When she came forward to confess, he announced that her faith had healed her and commanded her to go in peace. The key moment in this narrative is depicted in a fourth-century fresco in the Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter, located in the outskirts of Rome (Plate 2).13

By the fourth century, two parallel legends – one Byzantine and one Western – connected the Gospel accounts of Jesus’s miraculous healing of the unnamed, bleeding woman with an individual named Bernice. The Eastern Orthodox version, written in Greek, is likely the earlier of the two legends and was retold in the fourth century by Eusebius of Caesarea, who claimed to have translated two letters exchanged between King Abgar of Edessa and Jesus into Greek from the original Syriac.14 The protagonist in the apocryphal correspondence is the Arab Christian King Abgar Uchama “the Black” of Edessa (r. 4 BCE–7 CE and 13–50 CE), who had requested Jesus’s assistance in curing him of an ailment.15 Tradition held that Jesus dictated a response to the king, which was delivered by the courier Ananias in the form of a letter, in which Jesus declined a personal visit, implying the need to undergo crucifixion (“I must accomplish everything I was sent here to do”). Instead, Jesus promised that he would send a disciple after his ascension.16 After Christ’s death, the apostle Judas Thomas sent Addai (also called Thaddaeus) to cure Abgar and to convert the people of Edessa,17 a city in northern Syria. Reference to an image was not originally included in the letters but instead added in later medieval versions of the legend. In these later embellishments to the story, prior to Jesus’s death, the king had sent to him an envoy, who was also the king’s court painter. Some versions of the legend recount that the painter rendered a portrait of Christ from life and gave it to Abgar. Another version attests that Christ washed his face and dried it, causing his features to be imprinted on the cloth. The main characters and plot in these later versions of the legend are visible in a painted icon, datable to the tenth century, from Mount Sinai in Egypt (Plate 3). In both versions of the story, King Abgar was healed by viewing the image of Christ’s face. Mentioned first in the Doctrine of Addai (a Syriac text, datable c. 400), the miracle-working image was considered an acheiropoieton (an image not created by human hands) and called the Mandylion, meaning cloth, napkin, handkerchief, or towel.18 Both the image and the correspondence were revered relics because of their miraculous abilities, such as allegedly having defended Edessa from a Persian sack in 544. The relics were transferred in 944 from Edessa to Constantinople, where they were housed in the palace chapel.

In the West, an adaptation of the Eastern legend first appears in the Gospel of Nicodemus, also called the Acts of Pilate.19 This apocryphal text was written by the mid-fourth century20 by several authors in Greek (although the text claims to have been written originally in Hebrew) with translations in Aramaic, Armenian, Coptic, Latin, and Syriac, among other ancient languages. Some – but not all – of the narrative is told from the point of view of Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judea. The text is organized into two parts: (A) the Trial, Death, and Resurrection of Christ, and (B) a variation on the texts in A but including the Descent of Christ into Hades.21 Within Part A, in a section about the trial, in which witnesses speak on Jesus’s behalf, is the short passage below that forms the entirety of Section VII. Here the given name Bernice (from the Greek berenikē, meaning bearer of victory, also transliterated from the Greek as Berenice, or Beronice in Coptic), was used to describe the woman with the hemorrhage:

And a certain woman named Bernice crying out from afar off said: I had an issue of blood and touched the hem of his garment, and the flowing of my blood was stayed which I had twelve years. The Jews say: We have a law that a woman shall not come to give testimony.22

Bernice is speaking in Jesus’s defense after he was accused of healing on the Sabbath and thus violating Jewish law.23 But these few sentences also serve to assert that under Jewish law, a woman could not serve as a witness at trial. Thus, this brief mention of the woman functions as part of a framing narrative for the drama of the trial in which the roles of women are clearly and publicly defined. In terms of unraveling the origin of the legend of Veronica, this initial association of the Greek given name Bernice with the anonymous woman with a hemorrhage from the synoptic Gospels comprises an important confluence and development. There are other unnamed figures in the canonical Gospels who are identified with new first names in apocryphal texts of the fourth century. For example, the soldier who speared Jesus at the Crucifixion is called Longinus for the first time in the Acts of Pilate.24 Additionally, the two thieves crucified on either side of Christ are named Dysmas and Gestas in the same text.25 Therefore, identification of a previously unnamed character from the Gospels is not a unique oc...