- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mathematical Modeling of Concrete Mixture Proportioning

About this book

The primary aim of this book is to put together an understanding of the appropriate principles of ensuring performance and sustainability of concrete. Broadly subdivided into three parts, first part contains the fundamental aspects introducing the constituent materials, the concepts of concrete mixture designs and the mathematical formulations of the various parameters involved in these designs. The second part is dedicated to discussing approaches and recommendations of American, British and European bodies related to mathematical modelling. Lastly, it discusses perceptions and prescriptions towards both the performance assessment and insurance of the resulting concrete compositions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mathematical Modeling of Concrete Mixture Proportioning by Ganesh Babu Kodeboyina in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Concrete and Modeling Concepts

1.1 Concrete—The Material

Concrete has been serving humanity as a material of construction in some form or the other from time immemorial. A look at the broad spectrum of progress in the production of concrete, like compositions and the various facets of their more recent modulations in trying to cope up with the requirements of sustainable construction, is highly fascinating. In a way, the present day concrete science and technology can be attributed to the seedlings of our ancestors in the eighteenth century, which was advanced and nurtured by the efforts of the nineteenth century investigators, culminating in phenomenally rapid advancement during the twentieth century. A lot of it can also be attributed to the influence and urgency in housing and infrastructure needs during and immediately after the two world wars. Apart from this, though concrete was the largest produced construction material and its use is considered to be one of the benchmarks of the standard of living of a community, it was often branded as a material of the past several times during its long history. However, its resurgence in many other forms and modifications, apart from the extraordinary progress made in its strength levels, always endeared researchers to look at it with fascination, if not admiration. There are also several other aspects that are often not so clearly understood even in its conventional utilization form, wrongly identifying it to be the primary culprit for all the inadequate and inappropriate practices adopted. This reinforces the need for a proper understanding of the design, production, transport, placement, curing and maintenance of the various concrete alternatives possible and their utilization potential for the vastly varying needs of society today. In addition, if appropriately deliberated and judiciously adopted, concrete has several advantages over its nearest rival, steel, with the different possibilities it offers, particularly the inexpensive maintenance and substantial lifespan of structures built with it.

The general perception of the professionals involved with the formulation, production and processing of cementitious composites like concrete is that with the substantial variations in the characteristics of the constituents as well as their quantities and distributions in the structure, it is not possible to put together a mixture design methodology even for the most basic strength parameter. It is indeed for this reason that the recommendations of most national organizations presenting the concrete mixture design methodology opine, suggest or insist that the resultant design should be appropriately modulated through trial mixes before its adoption in field. Naturally, if this was to be the status of knowledge or the efficacy methodologies being presented, one should presume that the idea of even attempting any mathematical modeling is evidently not even meaningful. Notwithstanding all this, there have been several efforts to bring about a semblance of clarity and order through various techniques into this aspect.

Concrete as a material of construction has made a huge difference due to the possibility of being able to essentially utilize local materials as a bulk of its content. Also, though the primary constituent, cement, is factory produced, the fact that it can be used by local artisans even with a very limited skill set makes it the choicest material for most construction. The complexity of the concretes required for the more intricate and demanding requirements, however, need an in-depth understanding of their production, transport, placing, curing and maintenance. Essentially, concrete is a conglomerate in its true sense, and in attempting to devise methodologies of arriving at the best stone-like mass, one could look at the examples of the different natural processes that led to the formation of the conglomerate itself. In a conglomerate, one could see that the different constituents have to be appropriately packed to ensure that the final fused mass due to the chemical, thermal and pressure effects over time result in the different possible strengths of the composite stone mass, varying from very high strength sand stones to the highly porous and fragile laterites that exist. Another aspect that may be of relevance in this context is to note that while the hardest of sand stones are in general fused mass of highly siliceous agglomerates formed under temperature and pressure, laterites are weak and mostly fragile masses of iron and aluminum oxides. This in a way shows the contribution of the basic constituents and the effectiveness of the binder in the final product, which probably is a good guiding principal for ensuring the appropriate characteristics in the case of concrete as well. In effect, the constituents of concrete have to be appropriately chosen and compacted to ensure a defect free system which, after the effects of hydration, could have the highest strength possible. Incidentally, it is clear from the above that neither just an effective packing nor alternatively an efficient bonding mechanism alone will ensure the highest strength. Herein lies the principal that it is actually the density and porosity that dictates the strength of concrete. One should also recognize the fact that it is the continuity in pore structure, which allows the permeation of the environment into the concrete mass, that is responsible for the deterioration and durability of the concrete composites.

The idea of bringing together even some of the widely varying thought processes of several research workers over the millennia or even attempting to comprehend all that has happened over the years even in the limited arena of concrete mixture designs is a daunting task, or to be more precise, next to impossible. However, it would probably be more appropriate and cohesive to look at the underlying principles that have guided the development of the concrete composites in general. Obviously even in such an endeavor, probably it is only possible to look at the broad perceptions of the individual research attempts and the processes that dictate the recognition of the various concepts. Needless to say, there are several different possibilities and paths that could be directing the way for the ultimate objective of being able to arrive at a logical conclusion and also project a broad perspective of what lies ahead.

1.2 Historical Developments

In an apparent answer to the self-generated question about the service life of concrete, Kanare (2009) suggests 9800 years as a possibility, reflecting on the building concrete floors at Yiftahel—a pre-pottery Neolithic culture unearthed in Israel. Studies on these floor samples show that they were made from calcined limestone combined with sand and stone aggregate, similar to present day concrete, with the limestone being completely carbonated and achieving a concrete strength ranging from 4900 to 6500 psi. It is apparent from the investigations that the civilization had sufficient knowledge of calcining lime for cementitious purposes and also producing different mixture combinations, clearly showing the rough porous base layer and dense bright white sanded finish coat. It was also opined by some that the reactions between oil shale and limestone during the crustal formation in Israel appear to have resulted in the formation of naturally occurring cementitious compounds.

The fundamental concept of cementitious composites is essentially very simple, driven by the requirement of having to bind the inert and appropriately graded aggregate and filler matrix through the cementitious binder paste. The concept in itself is nothing new and owes its existence from prehistoric ages of times immemorial where in the use of simple mud mixed with clay initially for stone walls which later was translated into the use of lime and even lime volcanic ash combinations for various Mesopotamian and Babylonian constructions of over 10,000 years old and much later Egyptian and Roman structures dating back to about 3,000 years. There have been several modifications of these initial principles of understanding of how to accommodate a maximum amount of inert filler materials while utilizing the least quantity of binder that is needed, as the binder is the one that needs to be specifically processed and thus becomes the most expensive of the entire cementitious composite.

1.3 Concepts of Modeling

Model by definition is a representation of an object or a concept, more often used to present it in a scale smaller or to depict it in a format that allows the visualization of the same from afar. Models could be direct visual representations of the object in the form of physical entities, drawings or sketches or could even be highly abstract representations of the concept. Most noteworthy of these are ancient scripts as in cuneiform writings or even the more modern scripts of certain languages that could be traced back to similar beginnings without having transformed or mutated into more accommodative scripts by themselves or through their transfusion with some others.

In the domain of structural engineering, physical scale models are often utilized to investigate the characteristics of materials, members and even structural systems. The modeling process is often defined by the requirements of the parameter that is being investigated. The use of models of half scale or smaller using actual materials in the structure or models of several orders of magnitude smaller using micro-concrete or even polymeric (acrylics or epoxy) materials was also adopted for simulating certain characteristics, essentially the stiffness. Acrylic models used to understand the stress distributions through fringe patterns as in photo-elastic experimental stress analysis techniques have been adopted successfully.

Comprehensive modeling of materials such as concrete, which is actually a composite, is often highly complex. Most often attempting to model the effects of size of the member, size of ingredients like aggregates, which will have an effect on the distribution as well as the microstructural properties of the interface, apart from the number of discontinuities that could affect overall behavior of the structure, particularly in terms of the failure characteristics, is a utopian task. At this stage, it is not proper to introduce all these parameters without an understanding of their existence and implications appropriately. It is enough to say that there is a phenomenal amount of research and discussion on the specimen size, making and testing for even establishing the simplest and most often considered the representative parameter, the compressive strength of concrete. This being so, a simple and yet representative mathematical model of the behavior or even the mixture design methodology for a concrete of a specified strength appears to be almost impossible, but yet attempted by several researchers through several different avenues, probably depending upon their experience and perception. The simplest of such efforts is just to relate any two specific engineering parameters through mathematical relationship, most often through a specific but yet in most cases a limited experimental investigation.

In this context it is only appropriate to recognize that many of the earlier interpretations of strength behavior of concretes is based on traditional experience and parameters that are probably generated as a part of broad spectrum of scientific knowledge. Even so, many of these have been time tested and give an insight into the fundamental mechanisms of concrete strength development of time. The volumetric proportions proposed earlier are indeed some part of such efforts to define the behavior of concrete in simple terms. Later efforts to understand individual constituents and the cement particularly have led to better understanding and interpretations of these traditional theories, which saw the use of scientific knowledge generated from experimental investigations into an understanding of concrete behavior. Naturally, methodologies which utilize reorganization of the experimental investigations through process like the design of experiments to evaluate a limited set of complex interactive parameters have come into existence for this purpose. However, overemphasis on simple constituent qualities or quantities for defining such design of experiments have resulted in erroneous if not highly myopic views on the behavior of concretes and their extended family of materials containing supplementary cementitious materials. Another group who are more at home with the theoretical and mathematical solutions has gone to apply the scientific axioms essentially generated for an entirely different scenario into an interpretation of concrete characteristics with limited success. Many of these methods present the behavior of concrete as a bound medium of particulate material with some interface. Analytical tools to visualize and discretize the distribution of particulate matter of different sizes in a medium is one way to look at the evolution, while a more global binary constituent materials behavior is the other extreme. Apart from all this, direct application of the effect of the different constituents through well-known mathematical solutions like partial differential equations, expert systems, fuzzy logic or even neural networks and combinations thereof have all been attempted and reported. It is certainly not possible to present this entire gamut of information in the simple topic of concrete strength behavior alone (without even looking at the possibility of understanding its durability and performance in the different environmental regimes) is a herculean task and probably will not serve any useful purpose other than being able to just be a rigorous compilation if at all.

1.4 Concepts of Mathematical Modeling

Mathematical modeling as accepted in recent times in simple terms is an effective representation of a process based on certain accepted and fundamental relationships that drive it. The need for such a representation was obviously felt by the scientific and engineering communities specifically to be able to predict outcomes without having to go through physically the entire investigation or experimentation involved in the process. Conceptually, in the most fundamental terms, mathematical modeling could simply mean a representation of the relationships between two parameters in the form of a graph or an equation.

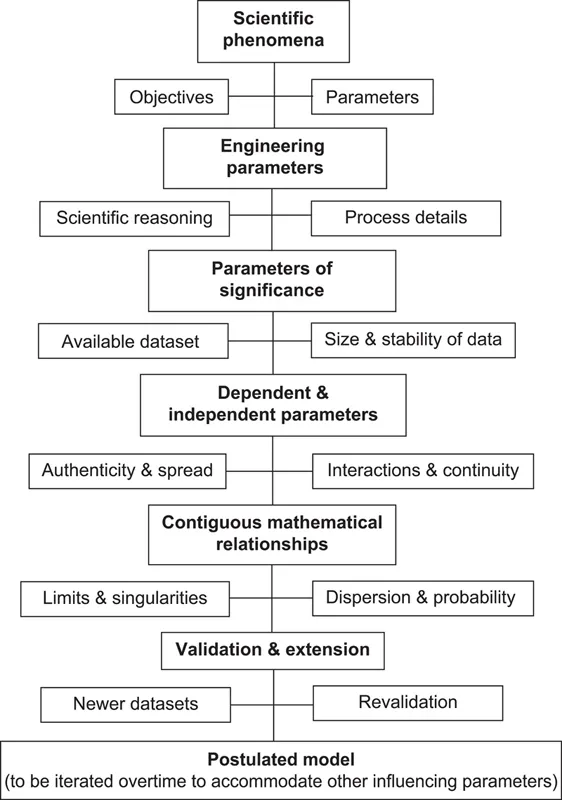

In an effort to mathematically model engineering processes particularly, researchers have adopted several different avenues, each of which have their own positive and not so positive effects in predicting the process. One of the first limitations and one can say is probably the size and representative panorama of the sample as many look at, which is often really the most obvious limitation. The second aspect that needs real clarity is regarding the representative parameters selected for establishing these relationships, which on several occasions appear to be arbitrary and without consideration to the known factors relating these. In a nutshell, the entire mathematical modulation of the modeling process can be described by a modeling tree presented in Figure 1.1. This can be explained briefly by the following few lines, which attempt to touch upon the major requirements to ensure that the processes are reasonably sound and could result in an appropriate solution.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Author

- 1. Concrete and Modeling Concepts

- 2. Constituent Materials and Processing

- 3. Concepts of Cementitious Mixture Design

- 4. Modeling and Unification Concepts

- 5. American Recommendations

- 6. The British Approach

- 7. Euro-International Vision

- 8. Perceptions of Performance and Sustainability

- 9. Very High Performance and Sustainable Compositions

- 10. Performance Regulatory Efforts

- 11. Future Prospects and Potentials

- Index