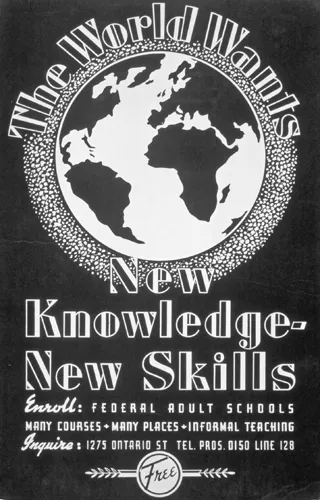

This is one of many WPA posters promoting knowledge and literacy. As noted in the Introduction, many of these works endorse education as a path to both personal and national renewal. Others highlight the expertise and social value of specialists such as doctors and urban planners. In doing so, these posters legitimized various forms of knowledge and ways of knowing: literary, scientific, aesthetic, and professional as well as that gained from personal experience and exploration. As educators argued, this type of multifaceted approach was necessary for meeting the complex needs of modern life and contemporary concerns related to recreation, conservation, health care, and housing, among other pressing social issues.

This chapter examines the form and content of these posters in the context of the FAP’s social mission, which embraced education as an important way of addressing a range of contemporary needs and issues. As the chapter indicates, in drawing a connection between the form and function of their work, FAP administrators and poster artists were participating in broader debates concerning the formal characteristics of socially engaged design. Equating modernism with functionality and usefulness, they suggested the success of a modern poster had less to do with the style it was rendered in than its ability to meet contemporary needs and communicate effectively with the public. In doing so, FAP artists approached design as a form of problem-solving akin to knowledge and literacy in its ability to manage the relationship between self and society in modern America. They also distanced FAP work from an association with propaganda and reinforced the notion that the FAP was a viable cultural project concerned with the welfare of the nation and its citizens.

The WPA and Poster Production

The production of these posters, as well as their form and content, was integrally tied to the Depression Era context in which they were created. After a decade of relative prosperity, America experienced one of the worst economic disasters in its history. Over a period of several days in October 1929, the New York Stock exchange suffered a severe crash that sent stock values plummeting. This incident was followed by a prolonged economic depression that devastated many Americans. By 1933, the year Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, nearly 25 percent of Americans were unemployed, thousands of banks had failed, and the gross national product had plummeted.

The government initiated a number of relief programs as part of its response to this crisis, including the WPA. Between 1935 and 1943, the WPA undertook a significant number of public works projects that resulted in the construction of buildings, roads, bridges, and parks, among other things. It also established several educational and cultural projects. United under the title “Federal Project Number One,” these cultural projects included the Federal Theater Project, the Federal Music Project, the Federal Writers Project, and the Federal Art Project.

The majority of the WPA’s posters were designed and printed by FAP artists, many working in official poster divisions. 3 The first poster division grew out of a Civilian Works Administration (CWA) project that New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia launched to promote various city initiatives. The “mayor’s poster project,” as it was called, was taken over by the federal government in 1935, becoming the first of many poster units established by the FAP. 4 Because the FAP considered poster production an “applied” or “practical” art, it distinguished these units organizationally from its “creative” divisions, which included mural and easel painting, sculpture, and fine art prints. 5

The FAP was, foremost, an employment program. Like many, artists were profoundly affected by the economic downturn. Their income shrank as employment opportunities waned and patrons cut back on purchases or stopped buying art altogether. The FAP hoped to relieve this situation by providing meaningful work in the arts. The project employed over 5,000 people at its peak, drawing at least 90 percent of its personnel from the relief rolls. 6 Approximately 500 of these individuals worked in the FAP’s poster divisions throughout the project’s existence. 7 The New York City unit, which was the largest, employed approximately 35 designers, 20 printers, and 10 to 12 film cutters at the height of its production. 8 Each FAP worker averaged between 95 and 110 hours of work per month and earned a salary consistent with his or her classification, which could range from “unskilled” to “supervisory.” 9 In New York, poster artists received between $21 and $27 per week. 10

By classifying poster production as an “applied” art, and its employees according to a skill-based hierarchy, the FAP distanced creative production from traditional notions of the artistic genius working in isolation. In fact, project administrators characterized FAP artists and designers as cultural workers fulfilling a useful and important social function. This challenged the notion that art is the domain of an elite removed from the practical needs of society. It also worked to mitigate critiques that the WPA was a waste of taxpayer money and a hotbed of subversive activity populated by freeloaders, radicals, and communists.

For similar reasons, project administrators publicized the fact that poster divisions fostered a collaborative environment, with each poster passing through many hands before its completion. Using rhetoric that aligned division work with industrial production, they suggested this approach encouraged “healthy anonymity” rather than “militant individualism.” 11 In their minds, this mode of production was consistent with the social mission of the FAP, as was the fact that few WPA designers signed their posters.

FAP designers created posters for a wide variety of agencies and organizations. Any government agency or tax-supported institution could commission a poster for public outreach. Private organizations could also commission work as long as the piece remained the property of the federal government or some other public agency. The only stipulation was that the project could not replace services that would have otherwise been supplied by a private design firm or business, a safeguard to protect already-struggling businesses and counter criticism of government interference in private enterprise. 12 The cost to the “co-operating sponsor” was nominal and depended on the division producing the posters, the quantity needed, the number of colors used, and the size of the finished product. 13 The dimension of these posters varied according to the needs of the sponsor, although many measured 14 × 22″, a size that was easy to both produce and distribute. 14

Agencies commissioning the posters displayed them in a variety of public institutions, including community centers, libraries, health clinics, hospitals, and schools. 15 They also placed them on street kiosks, in shop windows, and in highly trafficked areas such as cafes, clubs, railroad stations, subways, and bus stations. 16 The New York City Park Department, for instance, displayed several thousand posters promoting the ice-and-roller skating facilities at Flushing Meadow Park in subways, busses, and trolley cars. 17

Co-operating sponsors would also use the posters to communicate with more specialized groups. According to a 1941 report, posters commissioned by the New York City Department of Docks were distributed to foreign consulates to promote the first U.S. foreign trade zone. 18 Other sponsors displayed WPA posters at conferences, expositions, and trade shows. The U.S. Travel Bureau, for example, hung posters by Alexander Dux, Martin Weitzman, and John Wagner at the National Sportsmen’s Show, the Detroit News Travel Exposition, the National Automobile Show, and the Boston Winter Sports Exposition to encourage tourism to national parks and other sites. 19

Initially, FAP designers painted posters by hand. 20 This approach, however, was soon abandoned due to the constraints it placed on productivity. Not long after the first poster division was established, New York artist Anthony Velonis introduced a silkscreen process that appealed to many FAP artists. Although some divisions continued to experiment with other printing methods, most chose silkscreening as their primary method of production. 21 The silkscreen process allowed FAP artists to produce posters quickly and on a larger scale than they had with hand painting. 22 It was also economical compared to other printing processes. Silkscreen stencils were less expensive than the plates used for other production methods, and there were fewer costs associated with mounting materials because silkscreen frames could accommodate different thicknesses of paper. 23 These advantages allowed the FAP to produce a large number of posters for a relatively small financial outlay. In 1937, for example, the New York City division printed 38,200 posters for only $753. 24 This ability to mass-produce works economically reinforced the FAP’s role as a viable and cost-effective social program. The mass production and distribution of these posters also meant they reached a wide audience, which was consistent with the WPA’s educational mission.