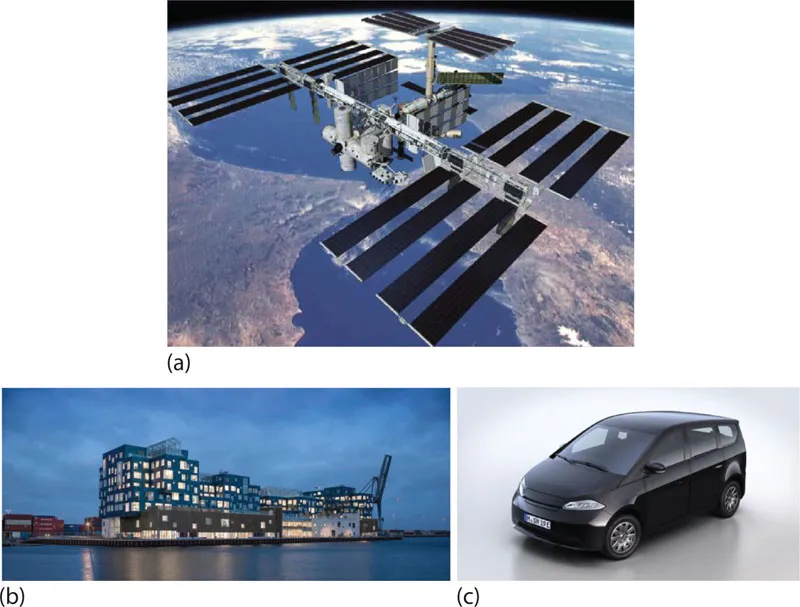

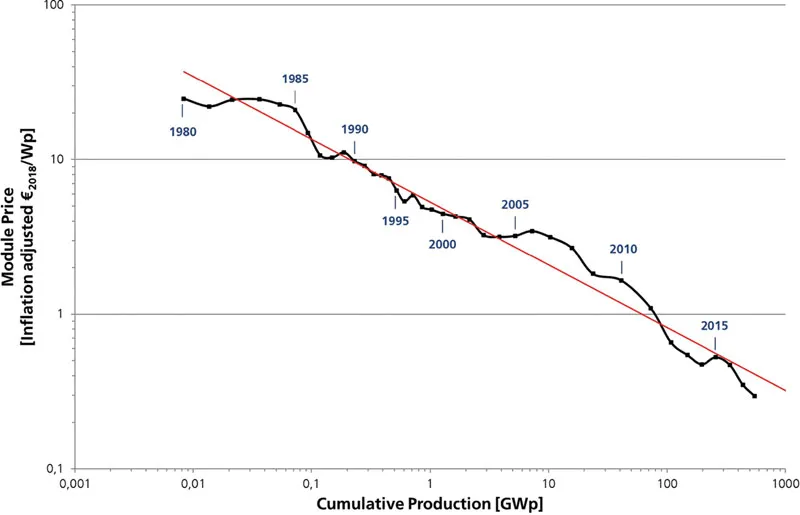

The idea of integrating solar technology into objects, such as products, buildings, or vehicles (Figure 1.1) is not new. Already in the 1950s people thought about integrating solar photovoltaic (PV) cells into smaller products that were not connected to the household’s mains to let them autonomously generate electricity for these products. Unfortunately, this never happened because electricity from the grid was cheap, and the price of germanium, a basic element in solar cells at that time, was too high. Therefore, the focus of embedding PV technology into small household objects shifted to integrating them into space applications such as satellites. Here, having solar panels onboard made much more sense because it meant that some functions of the satellite could function independently using the power of the sun. In this context, photovoltaic technologies result in the generation of power from photons, the smallest energy packages contained by solar irradiance. In space, higher risks and costs were involved compared to the everyday household objects allowing the use of expensive advanced PV materials, such as gallium arsenide, in solar cells applied in satellites. PV developments in space have been dazzling, for instance, the International Space Station contains more than an acre of solar arrays powering the station, making it the second brightest object in the night sky after the moon, according to NASA (Figure 1.1). Since the development and production of solar technology, now nearly 70 years ago, the focus has been on price reduction and increasing the efficiency of the solar PV technologies. Scale has been an important factor. Something that is new, and only available in a small volume, is expensive, whilst by producing on a mass scale, prices will lower. In the last 40 years, each time the cumulative production of the silicon PV modules doubled, the price went down by 24% (FhG-ISE 2019), see Figure 1.2.

Now that solar PV modules are being produced on a very large scale, their price has decreased immensely. To give an idea, at present (in 2019), a nominal power of 600 GW of PV systems is installed worldwide, and 100 GW of PV modules are annually produced to be installed. This situation has resulted in a (2019) price for mainstream PV modules of just 25 ct/watt-peak (PV Magazine 2019). At present, in some sunbelt countries, PV systems can therefore generate electricity at just 3 ct/kWh. This is lower than the cost of electricity produced by a coal plant. It is expected that this trend will continue.

Currently, the efficiency of mainstream PV modules, which for 95% of the market share are made of silicon solar cells, is in the range of 16.5%–18%. This means that such PV modules, under an irradiance of 1000 W/m2, generate a power of 165–180 W/m2. Because the detailed functioning of PV cells and PV modules goes beyond the scope of this book, we refer to the Chapter 3 for a short overview of PV materials, PV cells, and PV modules as well as several standard indicators that are common for addressing the performance of PV applications. The indicators are efficiency and nominal power, watt-peak, and performance ratio. More information about the fundamentals of PV technologies can be found in the recently published book Photovoltaic Solar Energy—From Fundamentals to Applications (Reinders et al. 2017).

Price reductions and a strong focus on enhancing the efficiency of PV modules was required for successful, broad adaptation of PV systems. Some people say that we even have been too pessimistic about the adaptation of solar technology. Namely, if this trend will continue in the coming years, electricity generated by solar PV systems in 2030 will be at least five times as high as in 2018 (IEA 2019).

To reach the goals of the Paris Agreement signed in 2015 (UN 2015), 100% renewable supply will be necessary by 2050. Therefore, a smooth energy transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources is one of the principal challenges that mankind faces at the moment. It will delay and hopefully stop climate change caused by the emission of large quantities of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Namely, these emissions largely originate from our fossil energy demand, which as such should be drastically reduced. In 2015, it was therefore agreed upon by the Paris Agreement that the global temperature rise should stay below 2°C, actually preferably below 1.5°C, compared to preindustrial levels. This change from a fossil fuel society to one based on renewable energy will require a huge effort by a varied group of stakeholders: the public, policy makers, scientists, industry, engineers, and designers. Many international and national agreements state that solar PV energy technologies will be one of the main contributors to achieve a prospective 100% renewable energy supply. And it is generally believed that both societal acceptance and technology development will be key to realize this goal. It is known that the interdisciplinary field of design can bring these two aspects together by the creation of products or systems, which people like to use.

As such, it is not only low prices and high efficiencies that will lead to a successful adaption in solar technology. Because solar PV modules can be visually observed in the public space, their image and visual appearance are becoming more important and might need changes (Figure 1.1). They no longer have to be black or blue, or directed at a certain, fixed angle toward the sun. They no longer have to contain a small part of the roof. Solar PV technologies can become a natural part of our environment, our buildings, and our cars. New PV technologies make it possible to create more diversity in placing and integrating solar cells, in terms of orientation and positioning, color, transparency, and even flexibility and form giving. These developments are needed to stimulate the large-scale adaptation of the technology, even more so in cities, where the energy demand density is higher than elsewhere, and space is rare. Since the price of solar electricity has lowered, there exists now an opportunity to consider the aesthetics features of PV modules and PV systems for innovative ways of integration in buildings and landscapes whether they are city or rural landscapes. Luckily, this is already happening in several PV projects.

The fact that citizens seem to be opposed against big solar parks is understandable. Namely, in their perception, beautiful nature landscapes are being filled with PV systems. It is important to be aware of a possible rejection of solar energy because in the recent past, people also weren’t supportive to windmills in their surroundings leading to the NIMBY effect, which means Not In My Back Yard. The Netherlands, or Low Countries, is a very flat country where sight goes far. Thanks to well-planned projects, windmills and wind parks have become an icon of the Dutch landscape. Perhaps, if we design them well, something similar will happen with solar PV systems (Figure 1.3). Design will be undeniably necessary to create a new solar revolution beyond the already initiated energy transition.

1.2 ASPECTS OF INTEREST FOR DESIGNING WITH PHOTOVOLTAICS

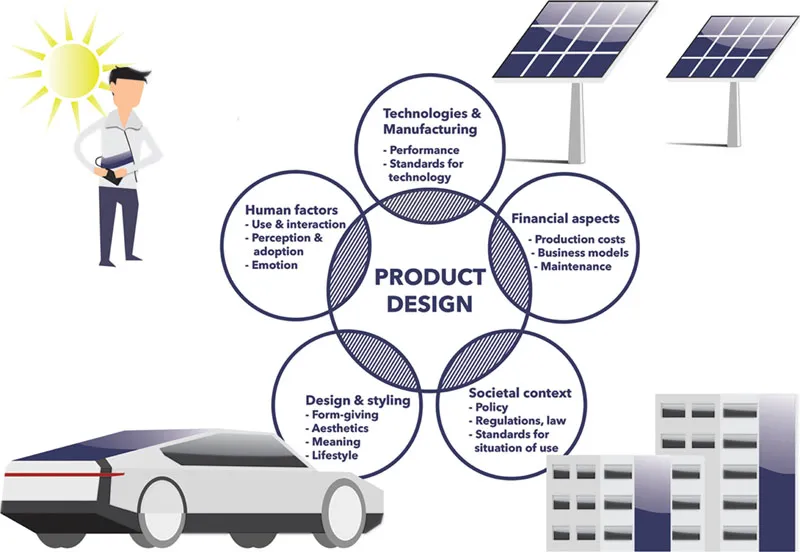

Despite the situation sketched in the previous section, at present, the application of PV solar cells and PV systems beyond primary energy production is still limited (Figure 1.4). Earlier work revealed that the design potential of PV solar cells and PV systems is often not fully used (Eggink and Reinders 2016); therefore, in this book, the opportunities and challenges of designing with PV materials and systems are explored in the context of five aspects that are relevant for successful product design.

The five aspects that are relevant for successful product design (Reinders et al. 2012) are: (1) technologies and manufacturing, (2) financial aspects, (3) societal context, (4) human factors, and (5) design and styling, which all together form the so-called innovation flower (Figure 1.5). These five aspects, the context for this book, are subsequently discussed.

Technologies and manufacturing deals with PV materials that are used and the manufacturing techniques that are used to create PV cells and PV modules. Also, the electronic equipment that is applied to convert, distribute, monitor, and store solar energy plays an important role.

The financial aspects deal with investments in solar systems and related PV products and the economic value of the energy produced.

The societal context plays an important role in the realization and acceptance of PV systems within society. Policy, regulations, laws, and standards are typically categorized as societal aspects. However, the public opinion on sustainability and the willingness to use PV technologies play important roles here. For instance, from a prior study, it was concluded that respondents were quite positive about PV products that have an environmentally friendly or a social character (Apostolou and Reinders 2016).

The fourth aspect of human factors deals with the use aspects of PV systems. This is especially important in the case of PV systems in smart-grid solutions and product-integrated PV. In the case of smart grids, for instance, the fact that energy should be used when it is available, or in moments when the generation costs are low, could compromise the usability of appliances when user interfaces of home energy management systems are not well designed (Obinna et al. ...