Dopamine (DA) is a member of the catecholamine family, which is composed of biogenic amines with a catechol ring structure. The family includes three members: DA, norepinephrine (NE), also known as noradrenaline, and epinephrine (Epi), also known as adrenaline. The term catecholamines is derived from their basic structure, which couples an amine side chain with a dihydroxyphenyl (catechol) ring. Historically, the catecholamines were discovered in the reversed order of their position in the biosynthetic sequence. This was due to the early recognition of their tissue location and ease of experimental manipulation (i.e., Epi in the adrenal gland, NE in sympathetic neurons, and DA as the dominant catecholamine in the brain).

Adrenaline, the prototypical catecholamine, was isolated from the bovine adrenal gland in 1901, while Dopa decarboxylase (DDC), the second enzyme in the biosynthesis of catecholamines, was first described in 1936 [1]. In subsequent years, all aspects of catecholamine homeostasis, including biosynthesis, metabolism, storage, release, and receptors, have been extensively investigated and become well documented. Notably, DA itself was recognized as an independent neurotransmitter (not only as a precursor of NE) only in the late 1950s. The concepts of the storage and reuptake of catecholamines, which were initially deduced from their pharmacological behavior, were firmly established following the identification and characterization of the large family of monoamine membrane transporters [2].

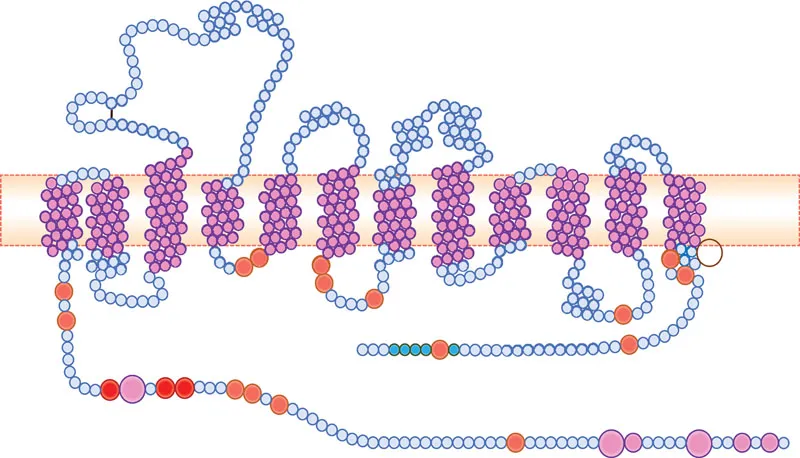

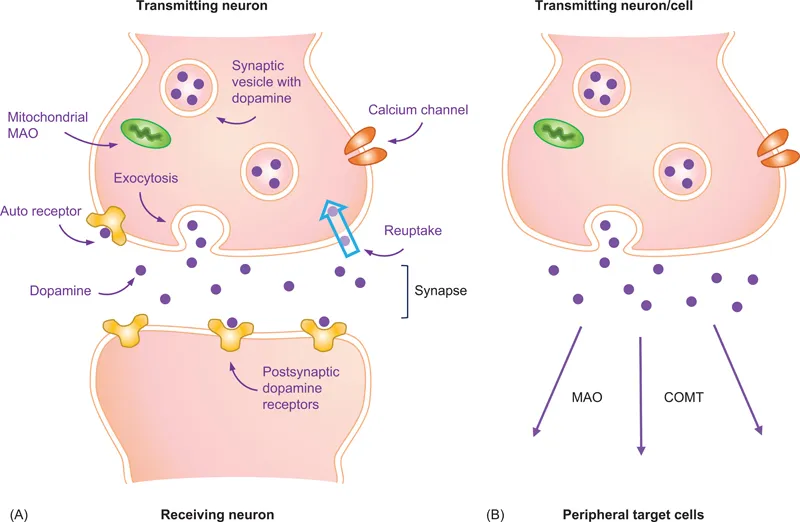

Homeostasis refers to the processes by which a living organism, tissues and/or cells keep their internal environment stable in spite of continuous changes in the conditions around them. The synthesis, metabolism, storage, release, and reuptake of DA are interrelated dynamic processes which differ in several respects between the “closed” system of the brain dopaminergic neurons, and the “open-ended” dopaminergic system in peripheral organs (Figure 1.1). In the closed configuration of the neuron/synapse/neuron, the concentration of released DA inside the very small space of the synaptic cleft can be as high as 5–10 μM. On the other hand, peripheral DA-producing cells can be quite remote from their target cells. Thus, the concentration of circulating DA, once it reaches the target cells, does not exceed 20–30 nM.

The wide disparity in the actual concentrations of DA at the target sites between the brain and peripheral sites should be taken into consideration when evaluating results of in vitro studies, many of which have used DA at high micromolar levels. This discrepancy may also explain some of the differences in the ability of certain dopaminergic drugs to alter the functions of brain vs. peripheral dopaminergic systems.

Most of the experimental data on DA homeostasis were obtained from research that was focused on brain DA. Nonetheless, PC12 cells, a cell line that was derived from a rat adrenal medullary pheochromocytoma and represents non-differentiated neuroblastic cells, have also been heavily used to study all aspects of catecholamine homeostasis. Whenever appropriate, similarities and differences in the features and regulation of central vs. peripheral DA are emphasized in this and the following chapters.

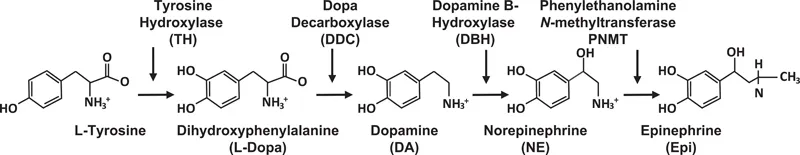

The three catecholamines, DA, NE, and Epi, are synthesized by four enzymes that act in sequence, as presented in Figure 1.2. The first enzyme, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), converts tyrosine to L-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-Dopa). TH serves as the rate-limiting step in the biosynthetic pathway of the catecholamines and has a rather restricted tissue expression. The more widely expressed second enzyme, DDC, also known as aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, generates DA from Dopa. Cells that express the third enzyme, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), can synthesize NE as their major product, while those cells that also express the fourth enzyme, phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), can produce Epi. Table 1.1 depicts the gene location, protein structure, major substrates, and selected inhibitors of TH, DDC, DBH, and PNMT.

1.2.1 Tyrosine hydroxylase

TH is a mixed function oxidase that uses L-tyrosine and molecular oxygen as substrates, and L-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and ferrous iron (Fe2+) as cofactors [3]. Tyrosine is one of the 20 standard amino acids used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a nonessential amino acid with a polar side chain group. Given its natural abundance, catecholamine levels are not influenced either by changing the dietary levels of tyrosine or by its parenteral administration, even at large amounts. Because of its essential role as a cofactor in TH enzymatic activity, a deficiency in BH4 can cause systemic deficiencies of catecholamines. One example of BH4 deficiency is the development of dopamine-responsive dystonia, characterized by increased muscle tone and Parkinsonian features. This condition can be treated with carbidopa/levodopa which directly restores dopamine levels within the brain.

TH is a 240-kDa tetrameric cytosolic enzyme which acts by introducing a second hydroxyl group on the phenol ring, thereby converting it into a catechol ring. TH has a lesser affinity for L-phenylalanine and no activity toward D-tyrosine, tyramine, and L-tryptophan. Effective inhibitors of TH include amino acid analogs such as α-methyl-p-tyrosine (α-MPT), α-methyl-3-iodotyrosine, and 3-iodotyrosine, all of which act by competing with the tyrosine substrate. TH is expressed in specific regions of the brain where catecholaminergic neurons are located, including the striatum, substantia nigra, locus ceruleus, olfactory bulb, and medulla oblongata [3]. As discussed in more detail in subsequent chapters, TH is also expressed in the heart, adrenal gland, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and in several other normal and malignant peripheral tissues.

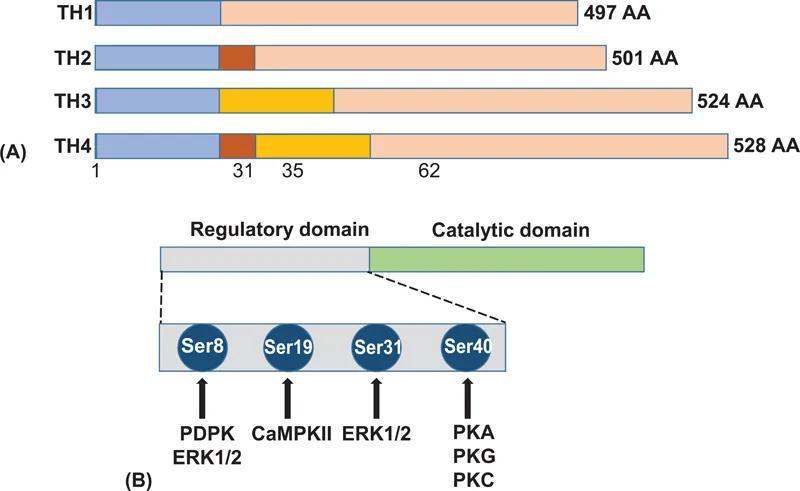

The human TH gene is located in chromosome 11p15.5 and is composed of 14 exons, spanning 8.5 kb. Targeted TH gene deletion in mice results in an early embryonic lethality, presumably because of cardiac failure. This may explain the absence of records in the clinical literature of a complete TH deficiency. Alternative splicing of the human TH gene in exon 2 generates four different mRNAs, which are translated into four TH subunits composed of 497–528 residues (Figure 1.3A). Each subunit contains an inhibitory regulatory domain at the N-terminus, and a catalytic domain at the C-terminus. Serines 8, 19, 31 and 40 in the N-terminal regulatory domain serve as phosphorylation sites that are involved in acute enzyme activation. Two histidine residues (His331 and His336), located within the pterin binding site at the catalytic domain, function as iron-binding sites.

TH is subject to both short- and long-term regulation [4]. Short-term regulation occurs rapidly at posttranslational levels and involves feedback inhibition by catecholamines, allosteric regulation, and enzyme phosphorylation. Each of the catecholamines, the end-product of the TH reaction, can inhibit enzyme activity by competing with the pterin cofactor. This results in a reversible enzyme inhibition by converting its active/labile form to an inactive/stable form. In dopaminergic neurons within the brain, end-product inhibition is often associated with the binding of DA to autoreceptors which are localized to various regions of the presynaptic neurons. Such a situation does not generally occur in peripheral DA-producing cells, most of which do not express DA autoreceptors. Allosteric effectors such as heparin, phospholipids, and polyanions do not directly alter the hydroxylation of tyrosine but, rather, increase the affinity of the enzyme for the BH4 cofactor.

TH is phosphorylated in response to nerve stimulation, as well as upon...