Accounting for M&A

Uses and Abuses of Accounting in Monitoring and Promoting Merger

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Accounting for M&A

Uses and Abuses of Accounting in Monitoring and Promoting Merger

About this book

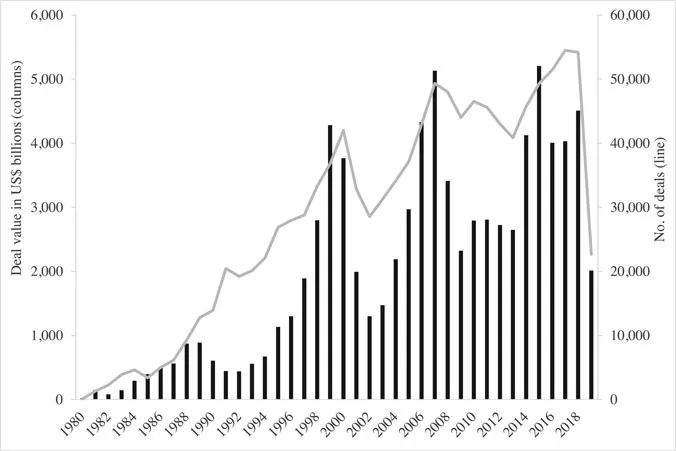

Spending on M&A has, in aggregate, grown so fast that it has even overtaken capital expenditure on increasing and maintaining physical assets. Yet McKinsey, the leading management consultancy, reports that "Anyone who has researched merger success rates knows that roughly 70% fail". The idea that businesses might be using huge and increasing sums of shareholders' money for an activity that more often than not leads to failure calls into question the information on which M&A decisions are based.

This book presents statistical studies, case material, and standard-setters' opinions on company accounting before, during, and after M&A. It documents the manipulation of annual accounts by acquirers ahead of share for share bids, biased forecasts of post-merger earnings by bidders, and devices to flatter earnings when recording the deal. It explores the challenges for standard-setters in regulating information flows during and after M&A, and for account-users wishing to learn from financial statements how a deal has affected performance.

Drawing on a wide range of international examples, this readable book is targeted not just at accounting specialists but at anyone who is comfortable reading the serious financial press, is intrigued by what is going on in the massive M&A market, and is concerned with achieving better-informed M&A. As such it might be of particular interest to business executives, lawyers, bankers, and investors involved in M&A as well as graduate students interested in researching or learning about the role of accounting in M&A.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

- In the accounts of many Western businesses spending on M&A has grown to exceed even that on new fixed assets. Much of Asia is following the same trend.

- The disappointing return on much M&A expenditure calls into question the (accounting) information on which the M&A decisions are based.

- The last 25 years have seen revolution and counter-revolution in the rules governing accounting for M&A. The resulting changes in mandated procedures can yield vastly different numbers for the acquirer’s earnings and its equity.

- The accounting standards currently in place for reporting listed companies’ M&A and its aftermath are not those deemed preferable by the UK regulators ASB or – before they were thwarted by corporate lobbyists – by the US regulators FASB. And they have subsequently been challenged by standard-setters and academics.

- Accountants have been accused of issuing misleading information to inflate the bidder’s share price artificially and distort M&A decisions: managing the bidder’s pre-merger earnings upwards, and providing upwardly biased earnings forecasts.

- Accountants have been accused of recording the integration of M&A deals in misleading ways – creating “cookie jars” from which illusory profits can be drawn in years following M&A; perpetuating anomalous treatments of intangibles in M&A; and misleadingly manipulating post acquisition write-offs.

- Notwithstanding the flaws in accounting around M&A, some important economic questions about the effect of M&A on company performance can best – or sometimes only – be answered with accounting data (suitably constructed to avoid the many potential pitfalls).

- In the accounts of many Western businesses spending on M&A has grown to exceed even that on new fixed assets. Much of Asia is following the same trend.

- The disappointing return on much M&A expenditure calls into question the (accounting) information on which the M&A decisions are based.

- The last 25 years have seen revolution and counter-revolution in the rules governing accounting for M&A. The resulting changes in mandated procedures can yield vastly different numbers for the acquirer’s earnings and its equity.

- The accounting standards currently in place for reporting M&A and its aftermath are not those deemed superior by the UK regulators ASB or – before they were thwarted by corporate lobbyists – by the US regulators FASB. And they have subsequently been challenged by standard-setters and academics.

- Accountants have been accused of issuing misleading information to inflate the bidder’s share price artificially and distort M&A decisions: managing the bidder’s pre-merger earnings upwards and providing upwardly biased earnings forecasts.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Abstracts

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- PART I Accounting procedures

- PART II Managing perceptions of performance around M&A

- PART III Using accounts to measure the impact of M&A on performance

- PART IV Concluding remarks

- Author index

- Companies/corporations (short form name) index

- Subject index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app