Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PJ, UK.

The rate at which greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere can be reduced by cutting emissions, but elevated levels of CO2 will persist for centuries. Climate models show that peak CO2-induced warming depends mainly on cumulative emissions and not the emission pathway (Matthews, 2018). It is, therefore, expected to become necessary to remove CO2 from the atmosphere in order to counter unacceptable climate change later in this century. Negative Emission Technologies (NETs) are the methods proposed for this. Nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) mainly emitted by agriculture and industry are also significant contributors to global warming, but this chapter focuses on carbon dioxide. NETs for CO2 are often termed carbon dioxide removal (CDR). It is a more efficient use of energy to capture carbon from flue gas than from the air, but even if applied quickly on a vast scale, it is expected that Flue Gas Capture (FGC) on its own will not be sufficient to meet policy goals—for example, peak warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial average temperature, the aspiration agreed at Paris in 2015 (Minx et al., 2018). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which has reported the causes and effects of global warming in great detail, is clear on the need to apply CDR:

“All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5 °C with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century” (IPCC, 2018).

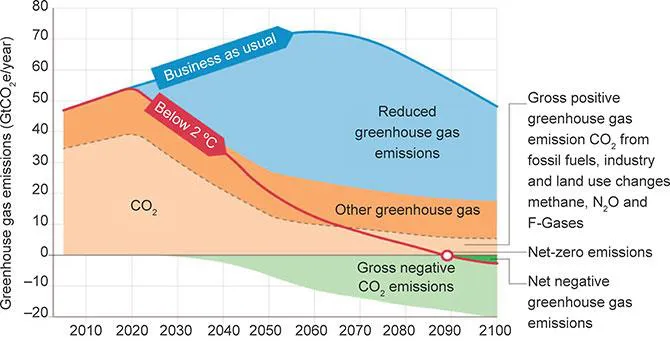

It is difficult to predict the precise timing and scale of CDR that might be needed, and many emissions scenarios have been considered by the IPCC. Figure 1 shows a typical scenario to the year 2100, in which peak warming is limited to 2 °C, and CDR is introduced from 2030 to ramp up to the scale needed. The ambition here is to draw-down around 810 Gt of atmospheric CO2 (range 440–1020 Gt) by the year 2100 and sequester it somewhere securely (UNEP, 2017). Greater emissions reductions could reduce this targeted draw-down (IPCC, 2018). Fuss et al. (2018) indicate a total NETs deployment across the 21st century equivalent to net draw-down of 150–1180 GtCO2 as necessary to meet the 1.5 °C target.

Whilst it is relatively simple to incorporate NETs into climate models, whether they can be applied at the scale needed or within the time frame assumed remains an open question. The impacts on people and ecosystems need to be considered, for these will be very large industries. Some NETs rely on well-known and proven technologies, but others still require a significant amount of research and development (Nemet et al, 2018). Moreover, recognising the objective of removing greenhouse gases from trie air raises questions, such as how it will be paid for and managed. At the very least, NETs will compete with other desirable activities for resources and investment. Conjuring these industries into existence and then operating them for, say, a century, with the objective of managing the global climate, is an undertaking unlike any previously attempted.

It is important to distinguish between methods of capturing carbon dioxide from flue gas or other waste gases (Carbon Capture and Storage – CCS), and carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere (CDR) followed by storage. Both CCS and CDR are responses to our failure to curb emissions of greenhouse gases sufficiently, but they have different characteristics:

a) CCS is a means of reducing emissions by using a process to capture carbon dioxide before it is released into the atmosphere, and storing the captured CO2 securely. CCS is intended to reduce emissions particularly from large stationary sources of CO2—power plants burning fossil fuel, cement factories, chemical plants and the like. Capturing CO2 from distributed sources like motor cars, aeroplanes and agriculture would be more difficult to do, and is not really envisaged. Deploying CCS will slow the global rate of emissions but will not affect the CO2 already present in the atmosphere.

b) CDR takes carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere into secure storage. It does not distinguish between CO2 arising from natural processes and from man-made emissions. Chemical processes for CDR need more energy than chemical processes for CCS, because the concentration of CO2 in the air is very low. Deploying CDR to an increasing extent will first decrease the rate at which CO2 is accumulating in the atmosphere; then, when the rate of CDR exceeds the rate of CO2 emission (i.e., net negative CO2 emissions), the atmospheric CO2 concentration will start to fall. When the rate of CDR equals the rate of emission of CO2 and all other greenhouse gases (in terms of CO2-equivalence), we will have net-zero emissions. In the scenario of Figure 1, this is projected to occur around 2090, after which we will have net negative greenhouse gas emissions.

Secure storage of CO2, meaning that it is removed from the atmosphere for a long time, is sometimes termed “sequestration” and CCS can also be taken to stand for Carbon Capture and Sequestration. Requirements for storage longevity, monitoring and verification are discussed in section 3.8. Another phrase sometimes encountered is Carbon Capture and Utilisation (CCU), describing the manufacture of products using biomass or captured CO2. The extent to which CCU can be regarded as either CCS or CDR depends on whether the product offers net long-term storage of CO2—this is discussed in sections 3.7 and 3.8.

In this chapter, we first describe, in section 2, the technologies that might be used to capture CO2 from the atmosphere, and indicate the chemistry involved. In section 3, we review options for storing the captured CO2. Using abiotic sorbents to capture CO2 is analysed in section 4, focussing in particular on the energy required and including an estimate of costs. Finally, we comment in section 5 on implications for setting policy.

2. Technologies for Capturing Carbon Dioxide from Air

Proposals to remove carbon dioxide from air have been reviewed by McLaren (2012), McGlashan et al. (2012), Fuss et al. (2018), Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering (2018) and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019). Broadly speaking, there are two main types of capture—by photosynthesis, which causes plant growth, or by means of an abiotic sorbent.

2.1 Capture by photosynthesis

In photosynthesis, growing biomass absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It reacts with water in the plant to form carbohydrate and oxygen in a reaction which can be represented as

| (1) |

Capture by photosynthesis is the basis of the coupled CDR system, BECCS (Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage), which takes CO2 from the air by growing crops that are used as fuel to provide useful heat or power. Carbon dioxide is then captured from the flue gas (a second capture of the CO2) and sequestered. Photosynthesis has the key advantage that it is powered by sunlight. However, growing plants specifically to capture carbon dioxide, whether in the sea ...