- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

With contributions from a distinguished group of world-builders, including academics, writers, and designers, this anthology of essays describes the process and discusses the nature of subcreation and the construction of worlds.

From Oz to MUD, Walden to Rockall, all the worlds featured in this volume share one thing in common: they began in someone's imagination, grew from there, and became worlds built with the assistance of multiple authors and a variety of different ideas and media, including designs, imagery, sound, music, stories, and more. The book examines this development, with examples and discussions pertaining to the process and the final product of the building of imaginary worlds, including some transmedial worlds.

World-Builders on World-Building is a fascinating deep dive into the practical problems of world-building as well as its theoretical aspects. It is ideal for students, scholars, and even practitioners interested in media studies, game studies, subcreation studies, franchise studies, transmedia studies, and pop culture.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

“Matter, Dark Matter, Doesn’t Matter”

An Interview With Lost in Oz’s Bureau of Magic

Why Oz?

| Henry Jenkins: | So, what makes Oz a great intellectual property? |

| Mark Warshaw: | I’d start with a character, Dorothy Gale, that is relatable and somehow timeless, helping kids find their way into this fantasy world. She gives us familiar eyes to look through as we see all this incredible stuff. |

| Darin Mark: | But that said, it’s worth noting that in the books, Dorothy is a much more passive protagonist than our version of Dorothy. Rule number one was creating a lead female character that has agency and makes bold choices, makes mistakes, and suffers her own consequences. So, right from the opening scenes of Lost in Oz, it’s Dorothy’s curiosity and her inability to let a problem go unsolved that triggers this entire journey, whereas originally Dorothy’s trip to Oz was a bit more haphazard than that. |

| Mark Warshaw: | But to your question, L. Frank Baum built this amazing architecture into the original canon. We can now – this many years later – go back and adapt Baum’s vision for a new generation. We never wanted to just tell the story that he told. We wanted to embrace his story, learn from it, and then springboard off of it to create an Oz for a modern audience. |

| Jared Mark: | At its foundation, it’s a story about somebody going far from home, far from her comfort zone, to a world she’s never experienced before, as a complete outsider. And once there, she embraces the singular mission of trying to go home again. But along the way, Dorothy meets all of these other characters and all of these other creatures that had their own problems to solve. The original Dorothy makes some of those problems her own. And so, now, she’s trying to solve her problem, but she’s also trying to help others along the way. For the modern character, she gets herself into this predicament, gets herself far from home. Why tell the story today? Here’s a story about going as far away from your home, as far away from your comfort zone as you could possibly get, and still having the wherewithal and the kindness to take on other people’s problems, form a community, and find a sense of purpose and place. And then to bring all of that knowledge back with you. |

| Abram Makowka: | You will find that by mid-second season, Oz is starting to feel more like home, and she has greater ambivalences about whether she wants to stay there or not. |

| Jared Mark: | She gets into the entire notion of what makes home a home, and that becomes a real touchstone for us, “Is home a place? A people? A feeling? What makes a home?” |

| Mark Warshaw: | This world that Baum set up doesn’t have many rules. And as it goes deeper and deeper into the books, Baum is making things up as he goes along. So, the possibilities are endless. Baum offers us this rich fertile ground to play in. And so, we took all those books and said, “That’s canon and that happened”, but then we take Geoffrey Long’s idea of negative space.3 [Editor’s Note: Long writes that negative space refers to “some parts of the story deliberately untold” so that it allows the reader to speculate and “fill in those gaps for themselves”. In this case, Warshaw suggests that future creators may also build on negative space in order to expand the fictional world so that it can yield new stories that address a new generation of readers and viewers.] Baum left us plenty of room within Oz where we can pick up the story. And as we started to weave the world together, we are taking the stuff that was originally there and speculating about what it would become today. What would happen if Dorothy went to Oz today? And by starting to answer that question, we began to build up the world where our story takes place. |

Reimagining the Land of Oz

| Henry Jenkins: | So, let’s build on that. How do you think about Oz today as opposed the Oz that would have existed 100-plus years before? How did you think about updating Oz? |

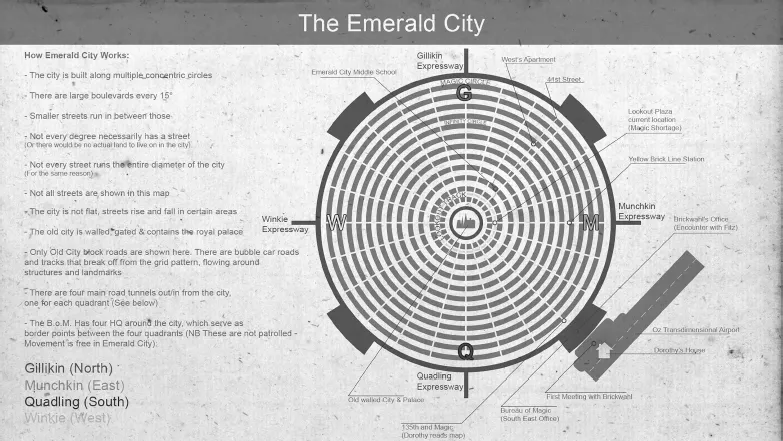

| Mark Warshaw: | We thought about the impact of people who have traveled to and from this world before, starting with the original Dorothy whose visit to Oz is now a historical event in our story. She’s now one of multiple visitors from our world who influenced this time line. So, what inventions did they bring into this world? What aspects of our world would have influenced the growth and evolution of the Oz of today? We wanted to turn the Emerald City into a big metropolis and make it look like a city that kids growing up today may have visited or actually lived in. This was a piece of concept art that our team in Scotland created [Figure 1.1]. When we saw this, this clicked as what Emerald City and the world of our show would look like. |

| We wanted that vibrancy and that kinetic energy: our Oz would be a bustling place that felt like a mix of Hong Kong or Tokyo or New York City. You take that, and you tether back to what Baum really laid [out] in his original Emerald City. We talked a lot about the different cultures, right? | |

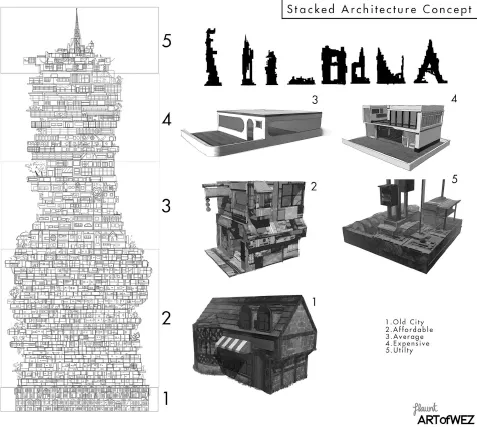

| Jared Mark: | Absolutely. What’s in the books happened, the characters in the canon existed. All that is history in this world. And we are now 100 years out from that. Well, let’s imagine what’s happened to the populations, to the geography, to the demographics of this world. We said, “What if we started with that circular city that Baum designed – the four quadrants? What if we expand from there and urban sprawls started happening?” And so, that area has gotten bigger and that old city is now the center of the widening circle. And now in those four quadrants, migrations have happened. Here’s our map [Figure 1.2]. We have the four quadrants, but we’ve got Gillikin Heights and New Bunbury and all these other neighborhoods. What happens if gentrification has happened in these different neighborhoods? So, the bottom layers of these cities, and the center of the city, is the old country. And it’s growing out from there until stacks on stacks on stacks of different types of architecture showing different time periods are built upon each other [Figure 1.3]. In story and in design, we’ll never throw anything away. We’re always building upon what’s been and that was a crucial central idea for us. |

| Mark Warshaw: | Well, what’s better than the foundation Baum laid out? It would be crazy to let that all go. Baum, in the later books, would just build upon what he’d already done – not being totally consistent. We could dig into all of his creations and pick and choose certain characters or certain story lines that served our needs. |

| Darin Mark: | So, the character of General Guph becomes our big bad in the second season. Well, if you really try to get down at the brass tacks of history and how he still exists and where he’s introduced in the canon and everything, it doesn’t totally work. So, we’re following our own Baumian logic as we’re going on. |

| Mark Warshaw: | We also took care in thinking of characters that could be immortal and could bridge those times. So, in our story, Glinda the Good is immortal. So, she was there and the Scarecrow too. So, they could serve as bridge characters coming from the Baum material to us. |

| Darin Mark: | In the original Baum books, there is so much negative capability; there were so many characters, places, and story lines running, some of which he never developed, some of which readers will not remember. One of our lead characters is Ojo, taken from Ojo the Unlucky, but we completely rebooted him. When we were deciding who we wanted to be regular characters on our series, we loved this guy. We saw a big opportunity in this character even though he didn’t play a major role in the books. This character who felt unlucky because he had this curse on him triggered something within us. We keep exploring that character. We ended up redefining him completely. But those are springboards that we found throughout the books. |

| Mark Warshaw: | Another good example would be Reigh, our take on the Cowardly Lion. What would a contemporary Cowardly Lion be like? We decided he would be a conspiracy the... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 “Matter, Dark Matter, Doesn’t Matter”: An Interview With Lost in Oz’s Bureau of Magic

- 2 The Making of MUD: Three Stories of Genesis

- 3 Rockall: A Liminal, Transauthorial World Founded on the Atlantis Myth

- 4 Making Worlds Into Games – a Methodology

- 5 Surveying the Soul: Creating the World of Walden, a Game

- 6 The Place of Culture, Society, and Politics in Video Game World-Building

- 7 Concerning the “Sub” in “Subcreation”: The Act of Creating Under

- Appendix: Types of World-Building

- About the Contributors

- Index