![]()

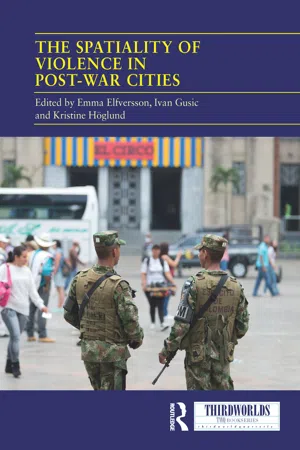

The spatiality of violence in post-war cities

Emma Elfversson

Ivan Gusic

Kristine Höglund

ABSTRACT

The world is urbanising rapidly and cities are increasingly held as the most important arenas for sustainable development. Cities emerging from war are no exception, but across the globe, many post-war cities are ravaged by residual or renewed violence, which threatens progress towards peace and stability. This collection of articles addresses why such violence happens, where and how it manifests, and how it can be prevented. It includes contributions that are informed by both post-war logics and urban particularities, that take intra-city dynamics into account, and that adopt a spatial analysis of the city. By bringing together contributions from different disciplinary backgrounds, all addressing the single issue of post-war violence in cities from a spatial perspective, the articles make a threefold contribution to the research agenda on violence in post-war cities. First, the articles nuance our understanding of the causes and forms of the uneven spatial distribution of violence, insecurities, and trauma within and across post-war cities. Second, the articles demonstrate how urban planning and the built environment shape and generate different forms of violence in post-war cities. Third, the articles explore the challenges, opportunities, and potential unintended consequences of conflict resolution in violent urban settings.

Across the globe, post-war cities constitute volatile flashpoints for renewed war and are frequent stumbling blocks in societies seeking to transition from war to peace.1 Beirut (Lebanon), Medellín (Colombia), and Monrovia (Liberia) are examples of such cities which have experienced war, no longer do, but still remain divided and contested. In addition to posing challenges in the transition from war to peace, post-war cities often function poorly as cities and constitute dangerous sites for people to live in. One central reason for the problems facing these cities is the high prevalence of post-war violence, which not only concentrates to post-war cities but also take urban forms and is unevenly distributed within them.

This collection of articles addresses the spatiality of violence in post-war cities. At the centre of attention is the intersection of urban and post-war dynamics which has implications for why, where, and how violence plays out. The articles are grounded in the recognition that post-war logics, urban particularities, and intra-city dynamics are all key dimensions that need to be accounted for in order to advance knowledge on the spatiality of violence in post-war cities. Post-war cities and urban violenc have been subjects of study across disciplines such as peace and conflict research, urban studies, criminology, planning, geography, economics, and social anthropology. Yet these fields have largely remained separate and conducted research without insights from each other. To bridge this gap, we bring together contributions from a range of disciplines which approach the study of violence in post-war cities from different vantage points. The merits of this approach are multifaceted since the different fields have complementary foci. Peace research, for example, has in recent years improved our understanding of the micro-dynamics of conflict-related violence and the everyday experiences of those exposed to such violence.2 Urban studies, in turn, have extensively theorised violence in the city, generating an in-depth understanding of its urban dynamics, its spatial distribution, and its effect on different political outcomes.3 Social anthropologists and criminologists have provided detailed accounts of the individual- and group-level dynamics and incentive structures that affect participation in different forms of urban violence.4

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Bringing together contributions from these and other relevant disciplines, addressing the single issue of violence in post-war cities from a spatial perspective, this collection of articles: 1) nuances our understanding of the causes and forms of the uneven spatial distribution of violence, insecurities, and trauma within and across post-war cities; 2) demonstrates how urban planning and the built environment shape and generate different forms of violence and insecurities in post-war cities; and 3) explores the challenges, opportunities, and potential unintended consequences of conflict resolution in violent urban settings.

This introductory article is structured as follows. It first lays out the theoretical departure points for this collection. It then presents the individual contributions, summarises the three main ways in which they jointly advance theory and empirical knowledge, as well as elaborates on how this collection of articles moves the research agenda on violence in post-war cities forward. It concludes by exploring some important avenues for future research.

Setting the stage: the post-war city, violence, and space

The spatiality of violence in post-war cities is of critical importance to understand how violence can be prevented, for peacebuilding in post-war cities, and for understanding how the violence-exposed people living in them are affected. A growing literature emphasises that cities are becoming increasingly central in armed conflict.5 The situation on the ground in contemporary armed conflicts – with Aleppo (Syria), Mogadishu (Somalia) and Donetsk (Ukraine) all cities subjected to large-scale violence and warfare – resonates with such claims. Because cities are densely populated and hold significant political, economic, and social but also symbolic value, the impact of urban warfare is often particularly high there.6 In turn, violence reduction strategies required will also be different in cities than in non-urban sites, since cities tend to be more diverse in their demographic set-up and because urban spaces are characterised by intimate contact.7

Three dimensions are important for capturing the dynamics of violence in post-war cities: the concentration of violence to post-war cities, its urban forms, and its spatially uneven distribution. First, violence tends to continue and sometimes remain high in post-war societies, regardless of whether the preceding war simply peters out or is formally ended through a peace agreement or ceasefire. Such violence includes both remnants from the preceding war (e.g. violence perpetrated by former warring parties or across conflict lines) and new forms of violence that rise in the aftermath of war due to poor rule of law, political vacuums, and unemployed former soldiers.8 Such post-war violence tends to concentrate to cities, a fact which is often attributed to the particularities of the urban setting.9 Cities are dense and heterogeneous; function through mixing and everyday struggles; and constitute important symbolic and actual (political, economic, social) assets in an ever-urbanising world.10 Such dynamics contribute to violence continuing and concentrating in post-war cities in several ways. Population density makes separation of antagonists impossible in urban contexts and instead forces people to live as ‘intimate enemies’11 – thus causing more clashes with ‘the other’ in post-war cities than elsewhere. This is evident in the case of South Africa, where the transition away from apartheid and the political conflict between rival movements ANC and Inkatha, was hampered by violence taking place in large informal settlements surrounding South Africa’s cities that were ‘in conflict with each other, or with more established townships, or in particular, with hostel dwellers over scarce resources such as employment, land and water.’12 Because of the general (and constantly accelerating) centrality of cities, different conflict parties often aim to control key urban areas. The result is that frontlines of macro-conflicts (both during war and after) often come to centre on and run through cities, with more violence usually ensuing.13 Urban micro-struggles over space inherent to the functioning of cities tend to become intertwined with macro-conflicts, aggravating existing conflict or resulting in renewed violence in post-war cities.14 The city’s density and constant mixing of people also blurs the distinction between civilians, on the one hand, and security forces or insurgents, on the other hand, thereby exposing civilians in cities to more collateral violence than elsewhere.15 Finally, the combination of urban anonymity and high streams of illicit revenues (e.g. drug dealing, trafficking, smuggling) tends to attract former fighters who in post-war cities find shelter, funds, and a levelled playing field, as well as opportunities to transform into criminal groups.16

Second, urban dynamics do not only lead violence to continue and concentrate in post-war cities; they also gener...