![]()

1 Introduction

The aim of this book is to compare the extent to which alcohol policy development in four European countries – Denmark, England, Ireland and Scotland – has responded to the emergence of public health perspectives on alcohol control, especially as developed and supported through the World Health Organization (WHO). While it will be described in more detail below, the ‘public health’ position on alcohol broadly argues that national governments have a duty to tackle alcohol-related harm by introducing regulatory control measures aimed not only at tackling ‘problem drinkers’ but at reducing consumption across whole populations. In describing the political journey of this principle in recent years, we critically appraise how it has operated in the European context within the constraints of EU ‘realpolitik’, and in national settings where local cultural, political and economic circumstances create both opportunities for, and barriers to, novel policy development. We also consider how this approach sits within the wider history of alcohol policy advocacy, which stretches back beyond the emergence of the modern public health approach in the late 1960s to the nineteenth-century temperance movements.

Historically speaking, political interest in alcohol waxes and wanes. At times it is an issue of intense political activity, as was the case internationally in the early decades of the twentieth century; at others, it moves down the political agenda. However, even when political interest is intense, alcohol policy tends to display a high degree of equilibrium (Baumgartner et al., 2014). That is to say, established social and political norms, the influence of powerful commercial stakeholders, and an aversion towards risk among policymakers often combine to limit the political viability of radical shifts in either policy framing or legislative action. Novel policy ideas face a range of systemic barriers that put them at a disadvantage compared to the status quo. This book will highlight some of the ways those barriers operate in regard to alcohol.

Policy development is about far more, however, than persuading the right people to follow a given course of action. It is, more fundamentally, about problem definition: in this instance, how alcohol ‘problems’ are understood by the general public and framed in policy circles (Greenaway, 2011). At the heart of the ‘public health perspective’ is the argument that alcohol problems exist on a continuum throughout populations rather than as a simple dichotomy in which ‘problem’ drinkers, and problem drinking, are clearly distinct from moderate consumption and drinking behaviour. By rejecting the notion that harmful consumption can be uncoupled from moderate drinking behaviours, contemporary alcohol policy advocacy challenges a dichotomous model of harm that was dominant in much of the developed world from the middle of the twentieth century.1 The translation of this idea into viable political action is a matter of achieving sufficient consensus on how alcohol problems are framed. It is, in that sense, not simply about evidence but about hegemony: about establishing ways of framing alcohol problems such that they become the default understanding among sufficient key groups to make policy change possible (or, indeed, inevitable).

In addition to requiring breaks in established political routines and a shift in the framing and conceptualization of alcohol problems, alcohol policy advocacy presents a direct challenge to the commercial interests of the alcohol industry itself. Because it rejects a dichotomous model of harm, which boxes alcohol problems off from the majority of consumption, and because its goal is a reduction in the basic volume of alcohol sold, the public health frame is opposed forcefully by the bulk of alcohol industry actors. For most producers and retailers, the prospect of state regulation of the supply of alcohol, with the ultimate goal of reducing the scale of the market, is anathema. In a market as diverse and complex as alcohol, there are, for sure, variations, and some ostensibly public health-oriented policies, such as minimum unit pricing, have garnered the support of some industry stakeholders (Nicholls and Greenaway, 2015). Nevertheless, the determined opposition of powerful commercial interests is, undoubtedly, a critical factor in the power dynamics of alcohol policymaking (Babor et al., 1996; Hawkins and Holden, 2012; McCambridge et al., 2013; Gornall, 2014).

Power, of course, is not monolithic but dispersed among an array of actors. Policymakers may be disproportionately swayed by the interests and lobbying muscle of the alcohol industry but they are also responsive to other sources of power. In regard to alcohol policy, the medical establishment is also a key player, especially in health departments. The support of the World Health Organization is not insubstantial in giving weight to the claims of alcohol policy advocates, nor is the formation of advocacy coalitions such as the Alcohol Health Alliance in the UK or the Global Alcohol Policy Alliance internationally (Thom et al., 2016). Furthermore, public opinion – especially as mediated through the mainstream press – retains significant influence in shaping policy. In the ‘court of public opinion’, alcohol policy is about far more than health: it is about personal freedom, pleasure, leisure, perceptions of tradition, national identity, and so forth. Policymakers, when approaching the subject of alcohol, will be mindful of far more than simply the real or predicted health impacts of a given policy. Where alcohol is concerned, health is only one facet of a complex social and political reality.

While much of this book describes the framing of alcohol debates over time, it is also concerned with understanding the dynamics of how policy works. In particular, it looks at how policy ‘streams’ have developed in the alcohol field, and how those streams converge and separate such that, under some circumstances, radical policy shifts become viable (Kingdon, 2011). From this perspective, policy is never simply a case of the best evidence, or even the best arguments, winning out. Indeed, as John Maynard Keynes quipped, ‘There is nothing a government hates more than to be well-informed, for it makes the process of arriving at decisions much more complicated and difficult’ (cited in Breckon, 2016: 4). Rather, the fixed mindsets and processes that, for most of the time, reinforce policy stability are only likely to be punctured when a number of sociopolitical forces align: when an issue is not only a source of raised public and political concern, but when policy solutions emerge that match both the public framing of a given issue and the ideological values of policymakers themselves. In looking at a number of case studies, this book will focus particularly on these dynamic processes: how, when and why does alcohol rise up the political agenda? How do different constructions of alcohol problems acquire scientific validity and how do they gain political traction? Where do policy solutions come from and how are they advocated for? How does alcohol policy align with ideological principles on both the left and the right, and are there cases where cross-ideological coalitions emerge which drive change in the regulation of alcohol?

The role of ‘advocacy coalitions’ is crucial in this process (Sabatier, 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993; Thom et al., 2016). In the context of ideological, systemic, commercial and political pressures to maintain a liberal frame for alcohol policy, advocates for more stringent alcohol control have needed to form wide-ranging alliances to create political momentum. Examples of alcohol control coalitions can be identified all the way back to campaigns for anti-gin legislation in Georgian England and can be traced – both directly and indirectly – from the Victorian and Edwardian temperance movements through to alcohol policy coalitions today (Harrison, 1971; Shiman, 1988; Greenaway, 2003; Nicholls, 2009; Yeomans, 2015). In all cases, the core principle that government should proactively seek to reduce consumption has drawn together a range of actors to formulate coordinated policy positions and advocacy activities, establish a public profile, maximize credibility, develop persuasive bodies of evidence and – ultimately – gain the ear of influential policymakers. In observing the journey of public health principles, this book will consider how advocacy coalitions have emerged, how they worked both to develop and promote an evidence base that supports more interventionist alcohol policy, and how they have established networks within governmental structures to a greater or lesser degree of success.

Thinking about alcohol policy

At stake in much contemporary debate on this issue is whether policy is ‘evidence-based’ or not: what the status of evidence on alcohol harms is, how evidence is used and abused, and how evidence-gathering and policy advocacy interact. There is some value in exploring the degree to which public policy on alcohol is evidence-based in different times and places, but (for reasons alluded to above) this is rarely the case in any pure sense of the term. There is also some value in arguing that policy should be evidence-based, but doing so needs to avoid the trap of assuming policymakers are ever purely rational, objective actors working beyond the realities of political calculation (Mulgan, 2005; Russell et al., 2008; Hallsworth et al., 2011). In understanding the relationship between evidence and policy, it is most important to remain sensitive to the degree to which social and policy problems, and the multiple evidence bases that address those problems, are socially constructed. That is not to say that problems are illusory nor that evidence is unreliable; rather, it is to say that how social problems are understood, described, analysed and responded to reflects the social contexts in which those processes occur.

By extension, how policy ‘problems’ are identified, and which policy ‘solutions’ are adopted or rejected also reflect not merely the validity of the science (or, indeed, the opinions of policymakers) but a complex interaction between social conditions, public and political discourse, research activity, market conditions and broader ideological principles. Indeed, the way in which problems are constructed is not only a consequence of complex social processes, but central to the way in which social power operates. As Carol Bacchi puts it, ‘We are governed through problematizations rather than through policies. Therefore, we need to direct our attentions away from assumed “problems” and their “solutions” to the shape and character of problematizations’ (Bacchi, 2015). This book follows recent work on problem construction and framing in both drug and alcohol policy (e.g. Thom, 1999; Stevens and Ritter, 2013; Nicholls and Greenaway, 2015; Katikireddi et al., 2014; Katikireddi et al., 2015; Bacchi, 2015). It is less concerned with the simple question ‘Is alcohol policy evidence-based?’ than with understanding the relationship between problem construction, evidence, advocacy and policy in complex social contexts where politics is moulded by relationships of power.

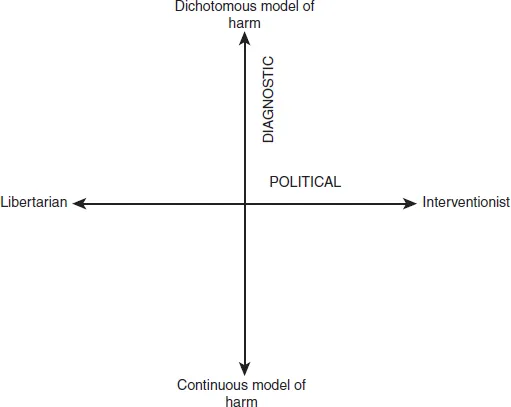

Policy ‘success’ is partly about sheer political influence: ultimately, money talks and so commercial actors are always at an advantage. However, it is also about effectively framing a problem such that it acquires traction across the policy landscape. One useful approach to placing alcohol policy ideas in context is to imagine them, schematically, as operating across two dimensions: a diagnostic dimension (how alcohol ‘problems’ are defined) and a political dimension (the level of state intervention considered legitimate) (Figure 1.1). In alcohol policy debates, the diagnostic dimension can be thought of as running from a ‘dichotomous’ problem-construction (in which ‘problem drinking’ is essentially different from ‘moderate drinking’) to a ‘continuous’ one (in which harms are disaggregated and spread across populations, albeit with varying degrees of intensity). The political dimension runs from libertarian (supporting maximum individual freedom) to authoritarian (maximum state intervention). The end points on each dimension are theoretical extremes: few people would pursue an exclusively dichotomous or continuous model of harm, or be entirely libertarian or authoritarian.

Figure 1.1 Diagnostic and political dimensions of alcohol policy

National prohibition movements, for instance, were strongly interventionist, but often varied in the degree to which they emphasized continuous over dichotomous harms. Contemporary public health advocacy is strongly committed to a broadly continuous model of harm, but argues for control policies rather than outright bans. Publicly, the alcohol industry tends to promote a dichotomous model aligned to a light-touch interventionism – though through their allied think tanks and lobby groups, they tend to shift much more forcefully towards libertarianism, albeit rarely calling for complete deregulation.

Within such a schema lies an array of complex and important distinctions. However, thinking about these dimensions can provide a useful heuristic for positioning moments in problem construction as well, importantly, as considering where particular problem frames have aligned with wider social and ideological contexts over time. Perhaps most importantly, however, is that it can serve as a reminder that the political and the diagnostic are always in relation to one another where alcohol policy is concerned. The issue is the nature of that interaction, not whether it is there at all.

This book, therefore, rejects naïve ‘rational-linear’ models of policymaking, which assume policymakers either do, or should, base their decisions primarily on the recommendations of value-free scientific researchers – were ‘value-free scientific research’ ever to exist (Russell et al., 2008; Cairney, 2012). Policy is, of course, frequently influenced or informed by empirical research findings but the process is political. Policymakers invariably balance research evidence with party politics, departmental interests, ministerial priorities, perceived public opinion, economic interests, and so on (Marmot, 2004; Stevens, 2011; MacGregor, 2013). In this context, public health evidence is one element in a complex struggle for policy influence (Smith, 2012). The ‘problem’ from this perspective, then, is not the lack of evidence-based alcohol policy, nor the amount of alcohol-related harm in a given society, but understanding how competing bodies of evidence, reflecting competing political, economic and sociological perspectives, achieve power in complex and dynamic political environments.

The commonly used analytical framework of ‘multiple streams’ policy analysis is helpful in making sense of this (Kingdon, 2011; see Katikireddi et al., 2015 and Nicholls and Greenaway, 2015 for prior applications to alcohol policy). Multiple streams analysis (MSA) is concerned with understanding the combined social, political and economic processes that both cause policy ideas or ‘solutions’ to form and to become politically viable. Like many other contemporary policy models, MSA asserts that policy change is dependent on the unpredictable confluence of social and political factors at any given time. Describing this process, Kingdon uses the image of ‘policy streams’ as part of his wider explanation of those moments, referred to as ‘policy windows’, when opportunities for policy change briefly, and temporarily, arise.

According to this framework, ‘policy windows’ can open when three ‘streams’ converge:

1 The problems stream: the process by which an issue emerges as an object of political concern. This can be a consequence of objective social change (e.g. a rise in alcohol-related mortality), but is more often shaped by a wide array of activities in which interest groups, journalists, public bodies, and so on compete to both frame a given issue and bring it to the attention of policymakers. Most potential policy ‘problems’ do not make it onto the political agenda, so this is an intensely competitive process involving advocacy, news agenda-setting, coalition-building and other processes far beyond the gathering and communication of research evidence.

2 The policy stream: the developments of policy ‘solutions’ to a given problem. Again, this is competitive and contingent upon both action and circumstance. Key to the process are so-called ‘policy entrepreneurs’: individuals or organizations who take the lead in presenting policy solutions and linking them, in both public and political discourse, to a giv...