![]()

1 Hempel’s scientific explanation models and their problems

Section 1 Introduction

We have to explain numerous events every day. In our daily life, we may ask: What is really going on during a solar eclipse? Why do I have a cold today? What is the reason that China has developed so quickly in recent years? Similarly, we have many types of explanations in scientific research. For example, college students write experiment reports to explain why an experiment rendered certain result. We might ask, then, is there any general form of explanations? If any, what is the logical form of scientific explanation?

At the beginning of human civilization, people tended to explain nature in mythological and anthropopathic ways, attributing all natural events to humanized gods. For example, when considering the question of why it rains or thunders, the ancient Chinese believed that there are dragon kings who take care of rain and a Thunder God who creates thunder. Therefore, “agents” in myth explained natural phenomena.

After that, many philosophers tried to give the world a metaphysical explanation as they searched for the ultimate cause. For example, Aristotle used his four causes (material cause, formal cause, efficient cause, and final cause) to explain everything in the world. However, if we continue to ask where the ultimate form, effect, and telos come from, we notice that Aristotle might have had no other choice but to appeal to God as the ultimate cause, which means we cannot get rid of a “metaphysical agent.”

Facing such a problem, some scientific theorists such as G. R. Kirchhoff and Ernst Mach claimed that scientists should ask how instead of asking why. The reasoning behind this is simple: to answer a how question, we only need a mathematical description of nature, which avoids the “metaphysical agent” problem that arises when searching for why.

Starting in the 1930s, circles within the philosophy of science began to focus on the general form of scientific explanations. At that time, Hans Driesch, a German philosopher and biologist, used the term entelechy to explain regeneration and reproduction in biology. He argued that every creature has its own entelechy, although it is invisible and even undetectable just like an electric or magnetic field. The complexity level of entelechy increases from plants to animals. For example, the gecko can regenerate its tail after losing the former one, and a human’s injured fingers can heal themselves automatically. These above examples are due to entelechy’s taking effect. Hans Driesch used the term extensively to explain most biological phenomena, and he even regarded the human mind as part of entelechy.

At the 8th World Congress of Philosophy in 1934, held in Prague, Rudolf Carnap and Hans Reichenbach both criticized Driesch, saying that his explanation introduced a new terminology but didn’t bring any new scientific discoveries; thus, as they argued, those explanations based on entelechy were no more than pseudo-explanations. To illustrate this idea, Carnap (1995) wrote a chapter specifically to discuss the general form of scientific explanation (pp. 12–19).

Afterwards, Karl Popper and Carl Gustav Hempel both had discussions about scientific explanation, but it is commonly believed that Hempel’s discussion is conducted more clearly and completely. Because of this, let us begin with Hempel’s scientific explanation models.

Section 2 Hempel and his contributions

Carl Gustave Hempel, also called Peter by his friends, was born in Oranienburg, a town near Berlin, on January 8th, 1905. Hempel was well educated in his early years, going to the University of Göttingen in 1923 to study mathematics under David Hilbert and Edmund Landau, while also learning symbolic logic from Heinrich Behmann. In the same year, Hempel went to Heidelberg University to study mathematics, physics, and philosophy. Under the guidance of Hans Reichenbach, Hempel began his doctoral studies at the University of Berlin in 1924. While studying in Berlin, he also followed Max Planck and John von Neumann to learn physics and logic.

Reichenbach’s two books Pseudoproblems in Philosophy and Logical Structure of the World deeply inspired Hempel, and, encouraged by Reichenbach, Hempel decided to visit the University of Vienna for one year. While in Vienna, he studied with Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap, and Friedrich Waismann. He was also able to engage in academic discussions with Otto Neurath, Herbert Feigl, Hans Hahn, and even with Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Due to the rise of Nazism in Germany, Reichenbach left Berlin in 1933, and Hempel chose Wolfgang Koehler and Nicholi Hartman as his new advisors, finally receiving his doctorate degree in 1934. Although he was not Jewish, he detested the dominance of the Nazis in Germany, so he seized an opportunity to immigrate to Brussels, Belgium, that same year. While there, Hempel became acquainted with Paul Oppenheim, an independent German scholar and chemistry industrialist. They did a great deal of work together, such as the well-known thesis “Studies in the Logic of Explanation,” which made scientific explanation become one of the central issues in the philosophy of science.

For the academic year 1937–1938, Carnap invited Hempel to visit the University of Chicago as his research assistant. After this, Hempel finally immigrated to the United States and taught summer courses at the City University of New York. In 1940, Hempel moved to Queen’s College where he stayed until 1948. From 1948 to 1955, he was an assistant professor at Yale University and published Fundamentals of Concept Formation in Empirical Science. In 1955, he was named the Stuart Professor of Philosophy at Princeton University, where he later published the masterpieces Aspects of Scientific Explanation (1965) and Philosophy of Natural Science (1966). From 1976 to 1985, Hempel spent his time teaching and researching at the University of Pittsburgh as a University Professor. Finally, after his retirement, Hempel lived his last years in Princeton, where he passed away on November 9th, 1997 (Fetzer, 2000, pp. xv–xxvi).

Section 3 Models of scientific explanation

1. The DN model of scientific explanation

Hempel put forward the Deductive-Nomological model of scientific explanation, which is also called the DN model. The structure of the DN model can be shown as follows:

- C1, C2, …, Ck (Initial conditions)

- L1, L2, …, Lr (General laws)

-

- E (Description of empirical phenomenon to be explained)

In this model, C is the initial condition, while L is general law, with both constituting the explanans. We can deduce E from the conjunction of L and C, which means the explanandum E is a logical consequence of the explanans.

Hempel provides an example about a frozen crack on a car radiator. The initial conditions are as follows:

- (a) The car has been outside for the whole night.

- (b) The outside temperature was below 25°F, and atmospheric pressure was normal.

- (c) The most pressure that the car radiator could bear is P0.

- (d) The radiator was full of water and sealed up.

General laws include:

- (a) The freezing point of water is 32°F under normal atmospheric pressure.

- (b) When the temperature is below freezing point and the volume is unchanged, the pressure of water will rise as the temperature goes down. There is thus a function relationship between temperature and pressure.

From these initial conditions and general laws, we can calculate the pressure P of water stress on the radiator, which is larger than the maximum pressure that the radiator can bear, P0. Therefore, we can logically deduce that the radiator cracked, which is the empirical phenomenon to be explained.

Hempel claims that the model of DN must satisfy three logical conditions and one empirical condition. Logical conditions are as follows:

- (a) Explanandum must be the logical consequence of explanans. In other words, the explanandum must be logically derived from information of the explanans; otherwise, the explanans is not enough to explain the explanandum. The aim of the condition is to ensure the correlation between explanans and explanandum is inevitable, not accidental. If we can logically reach explanandum from explanans, explanandum must be true when explanans is true. This condition is also called the deductive thesis.

- (b) Explanans must include general laws, and those laws are necessary when deriving explanandum. Inclusion of general laws is to ensure that the derivation of explanandum from explanans is replicable and also regular. This condition is also called the covering law thesis. Certainly, explanans usually also includes descriptions, which are initial conditions and not lawlike.

- (c) Explanans must include empirical contents, which means that at least the explanation can be tested by experiments or observations in principle. Therefore, Driesch’s entelechy is excluded from scientific explanations of life phenomenon since entelechy cannot be tested through experimentation or observation.

The DN model needs to satisfy an empirical condition as well: statements consisting of explanans must all be true. If general laws or initial conditions are false, it is not a scientific explanation even if we can derive the explanandum from the explanans.

2. The IS model of scientific explanation

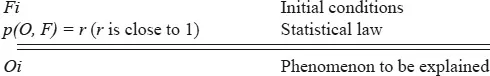

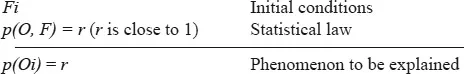

Dealing with statistical explanations in scientific research, in 1962 Hempel devised the Inductive-Statistical model (or IS model), based on the DN model. The structure of the IS model is as follows:

For example, take the condition “I feel a cold breeze after sweating” as an initial condition. People who feel a chill after sweating don’t always get a cold, but they do have a higher chance (maybe 80% or higher) of being attacked by a cold. Therefore, the law we have is a statistical one: catching a chill after sweating means an 80% possibility of catching a cold. The conjunction of initial condition and statistical law support the explanandum “I caught a cold” to a high degree, so it is a scientific explanation.

It is noteworthy here that we can logically derive “I have an 80% possibility of catching a cold” from initial conditions and statistical laws. For this sort of inference, Hempel coined the term Deductive-Statistical model (DS model for short) (Hempel, 1965, pp. 380–381). The logical form of DS model is as follows:

However, the DS model only shows us the possibility of a specific event, such as “I have an 80% possibility of catching a cold,” instead of a certain event such as “I caught a cold.” Therefore, Hempel paid more attention to the DN model and the IS model.

Based on the logical form of the IS model, we can only logically derive “I have an 80% possibility of catching a cold” without reaching the explanandum “I caught a cold.” Therefore, with the IS model, explanans gives explanandum a high level of support, but the explanandum is not inevitable. The inference here is inductive, not deductive. Accordingly, there are two lines between explanans and explanandum in the IS model in order to show the differences when contrasted with deductive derivation of the DN model (one line between explanans and explanandum).

The IS model must satisfy three logical conditions and two empirical conditions. The logical conditions are as follows:

- (a) Explanandum must have a high possibility of being derived from explanans.

- (b) Explanans must include at least one statistical law that is necessary for derivation of explanandum.

- (c) Explanans must include empirical content, which means, at least in principle, that the explanation can be tested through experimentation or observation.

To continue, the empirical conditions are the following:

- (d) Statements of explanans must be true.

- (e) Statistical laws of explanans must satisfy the requirement of maximal specificity (RMS for short).

The conditions (a)–(d) are basically the same as the conditions of the DN model. The fifth condition of the IS model is to choose the maximal specific sample. For example, Jack passed out after eating a pound of candies. If we used the statistical law that people may pass out after eating a pound of candies with a possibility lower than 1 in 10,000, this is too little for a satisfactory explanation. However, if Jack is diagnosed with diabetes and there is a law that people suffering from diabetes have a 99% probability of passing out after eating a pound of candy, then we have the maximal specificity of Jack’s case and have therefore explained his passing out successfully.

Hempel proposed both the DN model and the IS model of scientific explanation, yet there are some notable differences between the two models:

- (a) Laws of the DN model are general deterministic laws, while the IS model usually uses statistical laws.

- (b) The inference of the DN model is deductive so that its results are inevitable, logical derivations. The inference of the IS model is inductive, which means the reliability of inferences is determined by the probabilities of laws. Even if the explanans is true, the explanandum may not happen as well.

On the other hand, Hempel points out that the DN and the IS models share a similar form: both include scientific laws, which is essential to explanations. Scientific explanations must include scientific laws, so the requirement is called the covering law thesis. Hempel (1965) also calls his models covering law models (p. 412).

3. Supplementary specification of scientific ...