eBook - ePub

Risk Management and Error Reduction in Aviation Maintenance

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Risk Management and Error Reduction in Aviation Maintenance

About this book

Although several U.S. and European airlines have started providing human factors training to their maintenance personnel, the academic community (some 300 academic programs in the United States and several others in Europe and Asia) has not yet started offering formal human factors education to maintenance students. The highly respected authors strongly believe in incorporating the human factors principles in aviation maintenance. This is the first of two volumes providing effective behavioural guidance on risk management in aviation maintenance for both the novice and the experienced maintenance personnel. Its practical guidelines assist both student and practising aviation maintenance personnel to develop sustainable safety culture. For the maintenance community it provides some theoretical discussion about the "Why?" for risk management and then focus on the 'How?' to implement a successful error reduction program. To help the maintenance community in making a strong case to their financial managers, the authors also discuss the return on investment for risk management programs. The issue of risk management is taken at two levels. First, it provides a basic awareness information to those who have little or no knowledge of maintenance human factors. Second, it provides a set of practical tools for the more experienced people so that they can be more effective in risk management and error recovery in their jobs. This invaluable book serves as a practical guide as well as an academic textbook. The book covers fundamental human factors principles from a risk management perspective. Upon reading this informative book, the audience will be able to apply the basic principles of risk management to aviation maintenance environment, and they will be able to use low-risk behaviours in their daily work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Risk Management and Error Reduction in Aviation Maintenance by Manoj S. Patankar,James C. Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Defining Risk in the Aviation Maintenance Environment

Instructional Objectives

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Explain the critical need to reduce the number of aviation accidents.

2. Explain the concepts of risk and safety in the aviation maintenance environment.

3. Discuss the effects of poor operational and maintenance practices on the design safety of an aircraft.

4. List some specific ways in which maintenance personnel can minimize risk.

5. List some of the different types of costs associated with a typical aircraft accident.

Introduction

Risk is the probability of an unfavorable outcome. If we consider the classic example of tossing a fair coin, each side of that coin represents an equally likely event. Hence, the risk of such a coin not landing on its “head” or “tail” is 50 %. In the aviation industry, risk could be expressed in terms of number of accidents per x-number of flight hours. The lower the number of accidents per x-number of flight hours, the lower the probability of accidents. Therefore, in ideal terms, the safest activity would have a zero probability of accidents. In reality, however, safety is dynamic as well as relative because it is the probability of an accident that is acceptable to a given society. In other words, as long as a society perceives the benefits of a certain activity to be greater than the risk of failure in that activity, that activity will be considered “safe” in that society. As that society learns more about the advantages and disadvantages of that activity or the means to minimize the risks, it will redefine the acceptable level of risk, and consequently “safety”.

This chapter presents a general overview of aviation safety data, a summary of maintenance-related aviation accidents in the past decade, and a discussion of how risk is introduced into a particular flight. We use the concept of normal operating envelope (NOE) to define the criteria upon which safety of flight depends. When any of the parties concerned with the safety of flight commits errors, they compromise the design safety of that flight and increase risk. We have connected the SHELL model developed by Hawkins (1987) with Ashby’s law of requisite variety (Ashby, 1956) to form a Hawkins-Ashby model of risk management. The chapter concludes that this combined model could be used to understand and manage risks such that the requisite degree of safety is maintained.

Aviation Safety Data

Aviation safety data are available through several reliable sources such as the Federal Aviation Administration (www.faa.gov), the National Transportation Safety Board (www.ntsb.gov), the Boeing Commercial Airplane Company (www.boeing.com), the International Air Transport Association (www.iata.org), the Flight Safety Foundation (www.fsf.org), and the Air Transport Association (www.airlines.org). Safety data from other countries is somewhat difficult to obtain; however, Internet sites such as aviation-safety.net provide worldwide airliner accident reports and some general safety data. In this chapter, we present data to illustrate the magnitude of aircraft operations and the corresponding levels of safety.

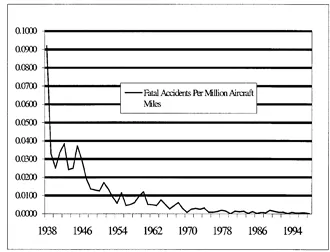

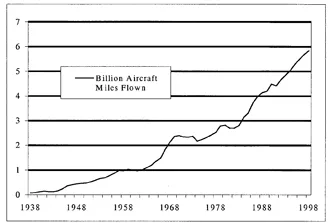

Accident statistics released by the Air Transport Association (ATA, 2002) indicate that the number of accidents of U.S. registered 14 CFR § 121 operators (scheduled air carriers) beginning in 1932 have decreased dramatically. Table 1-1 presents some NTSB’s standard terms and their definitions. Figure 1-1 illustrates a stable accident rate since 1982 while Figure 1-2 illustrates the concurrent increase in the number of passenger enplanements.

The net result of these changes is that if the accident rate does not decrease beyond the 1999 level, the number of § 121 accidents in the future would increase dramatically. The forecast accident rate is one § 121 aircraft per week by the year 2010. Therefore, the present accident rate, although substantially lower than any other modes of transportation, will probably not be acceptable as the passenger enplanements continue to increase. In other words, the society is likely to expect a much lower level of risk for air travel for it to continue to be safe in the year 2010.

Table 1-1: Some NTSB’s terms and their definitions

Accident: an occurrence associated with the operation of an aircraft that takes place between the time any person boards the aircraft with the intention of flight and all such persons have disembarked, and in which any person (occupant or non occupant) suffers a fatal or serious injury or the aircran receives substantial damage.

Fatal injury: any injury that results in death within 30 days of the accident.

Serious injury: any injury that requires hospitalization for more than 48 hours, results in a bone fracture, or involves internal organs or bums.

Substantial damage: damage or failure that adversely affects the structural strength, performance, or flight characteristics of the aircraft and would normally require major repair or replacement of the affected component.

Incident: an occurrence other than an accident associated with the operation of an aircraft that affects or could affect the safety of operations.

Level of safety (or risk): fatality or injury rates. Only past levels of safety can be determined positively. Accident rates are closely associated with fatalities and injuries and are acceptable measures of safety levels. Fatality, injury, and accident rates are benchmark safety indicators. Current and future safety levels must be estimated by other indicators or by extrapolating past trends.

Primary, secondary, and tertiary safety factors and indicators: these safety factors and indicators describe the relative “closeness” between the measured safety factors and the fatality, injury, and accident rates. Theoretically, primary indicators provide the best measures of changes in safety, followed by secondary and tertiary indicators. In practice, some tertiary indicators are more readily available and more accurate than primary indicators.

Primary factors: these factors are most closely associated with fatalities, injuries, and accidents. Accident/inciaent causal factors, such as personnel and aircraft capabilities and the air traffic environment, are examples. Incidents and measurable primary factors are primary indicators.

Secondary factors: these factors influence the primary factors. Airline operating, maintenance, and personnel practices, along with federal air traffic control management practices, are examples. Quantifiable measures of these factors, such as aircraft or employee utilization rates, are secondary indicators.

Tertiary factors: these factors include federal regulatory policy and individual airline corporate policy and capabilities that influence the secondary factors. An example of a tertiary indicator is the result of federal air carrier inspection that quantifies the extent of the carrier’s regulatory compliance.

Figure 1-1: Decline in fatal aircraft accidents since 1938

Figure 1-2: Dramatic increase in aircraft miles flown

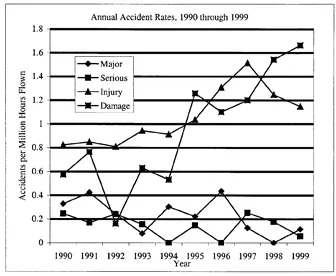

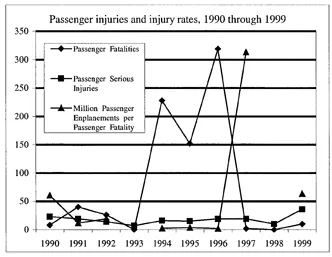

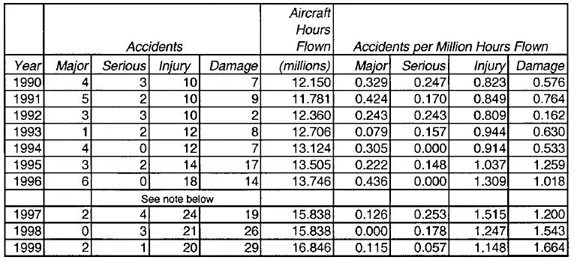

Now, if you review Figures 1-3 and 1-4, you will realize that aircraft damage and passenger injury are on the increase while serious accidents have diminished. Next, figure 1-3 shows year-by-year accident rates from 1990 through 1999 for 14 CFR §121 Air Carriers. Figure 1-4 shows Passenger injuries and injury rates for recent years. Finally Tables 1-2 through 1-6 support those figures with numbers of crashes, injuries, fatalities, and aircraft destroyed sorted by NTSB classification of accident severity.

Figure 1-3: Annual accident rates from 1990 through 1999 for 14 CFR 121 Air Carriers

Figure 1-4: Passenger injuries and injury rates from 1990 through 1999

Table 1-2: Accidents and accident rates by NTSB classification, 1990 through 1999, for U.S. air carriers operating under 14 CFR § 121

Note: Effective March 20, 1997, aircraft with 10 or more seats must conduct scheduled passenger operations under 14 CFR 121.

Definitions of NTSB Classifications

Major – an accident in which any of three conditions is met:

•a Part 121 aircraft was destroyed, or

•there were multiple fatalities, or

•there was one fatality and a Part 121 aircraft was substantially damaged.

Serious – an accident in which at least one of two conditions is met:

•there was one fatality without substantial damage to a Part 121 aircraft, or

•there was at least one serious injury and a Part 121 aircraft was substantially damaged.

Injury – a nonfatal accident with at least one serious injury and without substantial damage to a Part 121 aircraft.

Damage – an accident in which no person was killed or seriously injured, but in which any aircraft was substantially damaged.

Table 1-3: Passenger injuries and injury rates, 1990 through 1999, for U.S. air carriers operating under 14 CFR § 121

| Year | Passenger Fatalities | Passenger Serious Injuries | Total Passenger Enplanements (millions) | Million Passenger Enplanements per Passe... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Boxes

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Defining Risk in the Aviation Maintenance Environment

- 2. Personal, Professional, Organizational and National Perspectives

- 3. Ergonomics, Human Factors and Maintenance Resource Management

- 4. Maintenance Safety Culture and Sociotechnical Systems

- 5. Virtual Airlines and Mutual Trust

- 6. Professional Habits for Aviation Maintenance Professionals

- 7. How Far Will Reliability Take You?

- 8. Return on Investment

- 9. Case Studies

- 10. Resources

- References

- Index