- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cockpit Engineering

About this book

Cockpit Engineering provides an understandable introduction to cockpit systems and a reference to current concepts and research. The emphasis throughout is on the cockpit as a totality, and the book is accordingly comprehensive. The first chapter is an overview of how the modern cockpit has evolved to protect the crew and enable them to do their job. The importance of psychological and physiological factors is made clear in the following two chapters that summarise the expectable abilities of aircrew and the hazards of the airborne environment. The fourth chapter describes the stages employed in the design of a modern crewstation and the complications that have been induced by automated avionic systems. The subsequent chapters review the component systems and the technologies that are utilized. Descriptions of equipment for external vision - primarily the windscreen, canopy and night-vision systems - are followed by pneumatic, inertial and electro-mechanical instruments and the considerations entailed in laying out a suite of displays and arranging night-lighting. Separate chapters cover display technology, head-up displays, helmet-mounted displays, controls (including novel controls that respond directly to speech and the activity of the head, eye and brain), auditory displays, emergency escape, and the complex layers of clothing and headgear. The last chapter gives the author's speculative views on ideas and research that could profoundly alter the form of the crewstation and the role of the crew. Although the focus of the book is on combat aircraft, which present the greatest engineering and ergonomic challenges, Cockpit Engineering is written for professional engineers and scientists involved in aerospace research, manufacture and procurement; and for aircrew, both civil and military - particularly during training. It will also be of great interest to university students specialising in aerospace, mechanical and electronic engineering, and to professional engineers and scientists in the marine, automotive and related industries.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

BetriebswirtschaftSubtopic

TransportwesenChapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Scope

The English word “cockpit” originally meant a gaming enclosure where a pair of domesticated male fowl fought. By the 16th century, the word also denoted the arena or pit of a theatre, and later the area on the orlop deck on a man-of-war where wounded seamen were treated1. By the 18th century it had been shifted by naval humour to describe the wheel well for the helmsman, and at the beginning of the 20th century it flew naturally into the aeroplane. Although there are other words for the workplace of the aviator, such as work-station, crewstation or flight-deck, this word has survived, perhaps because it carries the connotations of frenzy, excitement, discomfort and danger so nicely. This is unfortunate because the aim of the designer is actually to provide the antithesis; a place of calm, professional assurance and safety.

The cockpit of the single-seat combat aircraft has probably been most challenging to design because a fast, manoeuvrable aircraft has little airframe space to house the pilot and the systems, and the pilot must be able to perform all tasks while exposed occasionally to violent forces. The environment can also be extremely hot or cold, bright or dark and it is invariably deafening. On the other hand, because superior performance of any kind enhances the military effectiveness of the craft and the chance of the crew surviving, the designers have received a lot of assistance. Aircrew have been studied to a greater degree than any other worker, and systems that can improve their performance have been the subject of intensive research and development effort. Like most of the engineering of a combat aircraft, the cockpit can be regarded as a forcing problem. Systems devised specifically for this context are commonly adapted for use in other types, and in other vehicles, after the initial cost of transforming an idea into a refined and tested embodiment has been absorbed by a military budget.

This chapter gives a very brief overview of the evolution of the ways that designers have accommodated crew in aircraft and provided facilities for them to perform their roles. The main objective is to state the need for equipment as a context for later chapters that describe the engineered form of the equipment.

1.2 Historical overview

Figures 1.1 to 1.6 illustrate how the single-seat combat aircraft cockpit has changed over the course of the 20th century from a biplane of the First World War to the configuration proposed for the Joint Strike Fighter that will enter service in the USA in several years time. The examples are intended to represent the contemporary standard and illustrate recognisable advances.

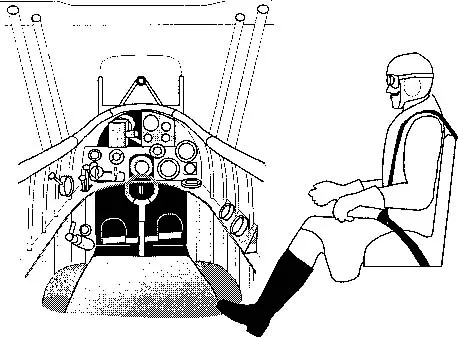

The first example in Figure 1.1 shows the cockpit of a typical First World War fighter, the SE5A, which was designed by the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough, England. The cockpit was essentially a reinforced opening in the top of the fuselage that had a padded leather edge and a small frontal glass windscreen. The seat, control levers and pedals were placed so that they could be reached by the pilot when he sat with his head and shoulders proud of the opening, and the necessary gauges and indicators were mounted on a plywood panel fastened below the front.

Figure 1.1 SE5A cockpit (1917)

The disposition of the components in this aircraft was as pragmatic as any contemporary automobile or locomotive. The pilot had to manage and fire one machine gun by operating the breech, which intruded into the cockpit through the top left segment of the instrument panel, while looking down the sighting tube to aim the whole aircraft at the target. Although idiosyncratic in many respects, the design was typical of the era in adopting a pair of rudder pedals, a central stick and a left-handed throttle as the main flying controls.

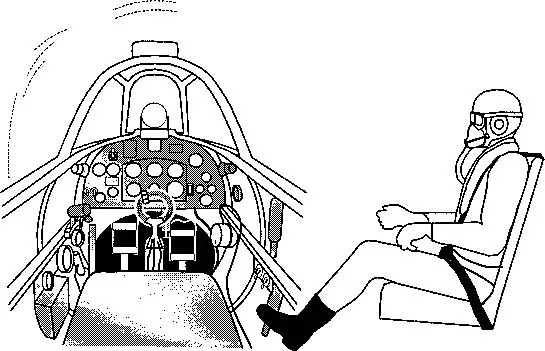

Figure 1.2 Spitfire cockpit (1940)

The second example, the Spitfire made by the Supermarine Aircraft Company shown in Figure 1.2, was a classic of the Second World War. It provided the pilot with vital enclosing protection against the cold windblast when flying at the newly attainable airspeeds, and with pressurised breathing air to counter the lack of oxygen at the newly attainable altitudes. More gauges were installed to show the flying state of the aircraft and the temperatures and pressures of the more complex engine, and there were more ancillary controls for the pumps and valves of the multiple-tank fuel system and for raising and lowering the undercarriage. The primary weapon was still the gun, but the pilot aimed the aircraft at the target using a lead-predicting gyro-stabilised gunsight and he fired multiple guns simultaneously by operating an electrical switch on the top of the stick.

Figure 1.3 Lightning cockpit (1964)

Figure 1.3 shows the cockpit of the English Electric Lightning. This represents the transformation needed to accommodate the extension of flight into the supersonic and stratospheric regime enabled by the jet engine, in particular, a pressurised cabin with a strong stiff canopy frame. It also illustrates the sudden expansion of display and control panels for the complex engines, re-heat boosters, fuel transfer cocks, communication radios, beacon-based navigation systems, central warning system and nose-mounted radar. The last made use of an electronic display device, a cathode ray tube (CRT), which was mounted just beneath the glare shield on the front instrument panel to the right of the gunsight. The CRT produced so little light that the pattern of blips marking the reflections from the objects illuminated by the radar beam could not be discerned unless the screen was shielded from sunlight by a rubber cowl. The panel also housed large, circular attitude and direction indicators and a large horizontal combined airspeed and Mach Number strip gauge. The rear-mounted engines created a relatively quiet ambience and enabled the pilot to see downwards over the aircraft nose. The ejection seat transformed the chance that the pilot would survive a mishap, and brought numerous complexities, including the need for a hard-shelled helmet.

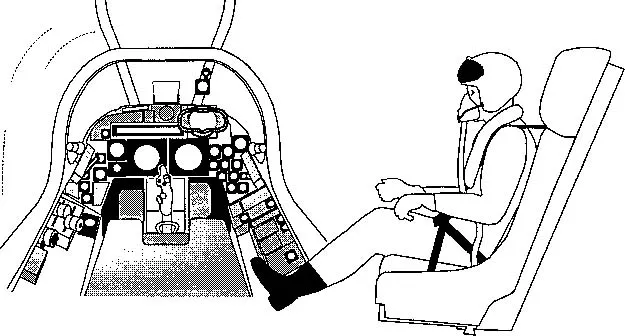

The fourth example, the Panavia Tornado, is perhaps the epitome of apparent complexity. As sketched in Figure 1.4, the glare shield and side consoles are awash with keypads and switches for the pilot to interact with the newly introduced navigation, communication and weapon aiming computers. The few evident CRT displays are substantially brighter than the Lightning’s radar display and incorporate filters to reduce glare, but they are squeezed onto the front panel, along with a large number of electro-mechanical dials and an intrusive head-up display (HUD). The latter can be regarded as an enlarged gunsight, in which the lamp-illuminated aiming reticule has been replaced by a set of symbols projected from a very bright CRT.

Figure 1.4 Front cockpit of a Tornado (1974)

Another CRT is hidden in the bowels of the Combined Optical Map and Electronic Display (COMED) on the front panel underneath the HUD, and the shell of the helmet provides an anchorage for another kind of electro-optical device, the night vision goggle. Although not apparent in the sketch, the introduction of the latter devices entailed illuminating the cockpit with compatible blue-green light.

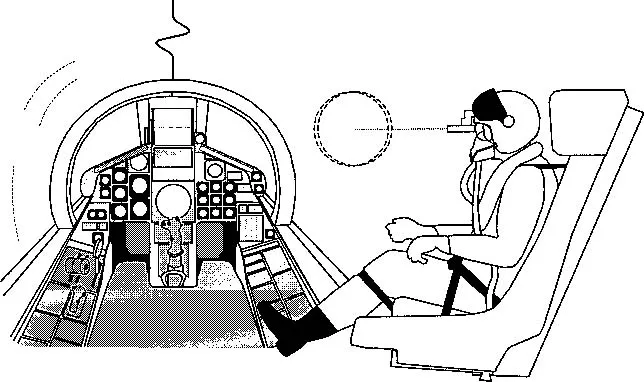

Figure 1.5 Eurofighter cockpit (1986)

The fifth example, the Eurofighter cockpit, represents the consolidated form of “glass cockpit” which arose from the rapid maturation of computing technology during the late 1980s and the adoption of digital electronics for the control all on-board systems. In this case, multifunction electronic display devices are used to show images generated by digital computers, and in comparison with the Tornado the layout seems remarkably well organised and uncluttered. The three full-colour displays are surrounded by keys that enable the pilot to select, for instance, tactical overviews, maps of differing scale or summaries of the, fuel, engine and systems states. The pilot has a variety of ways to interact with the on-board systems, such as the keypad on the left coaming for entering navigation data, the switches embedded in the hand-grips for fast, routine selections – the HOTAS (hands-on-throttle-and-stick) idea – and he can also make some selections by voice command. So that less time need be spent looking into the office, the HUD imagery is larger and more informative, and symbolic information is also provided by the helmet-mounted display (HMD), at night overlaid onto an intensified view of the world.

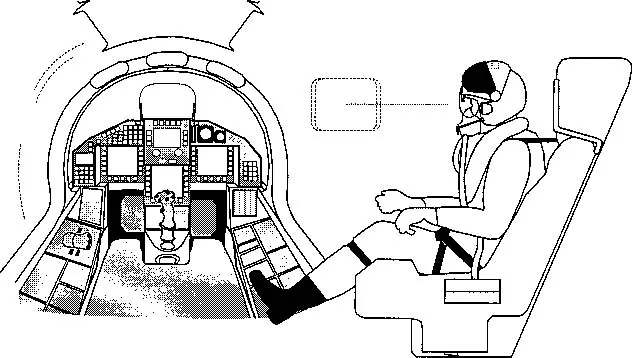

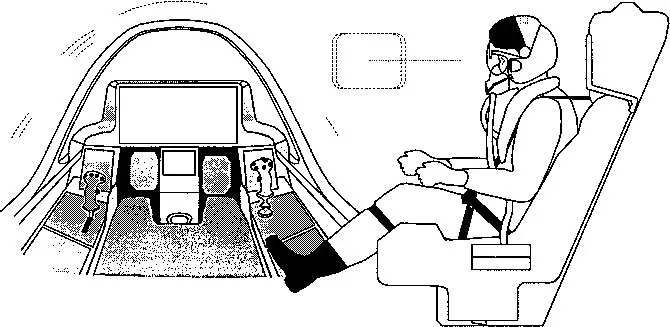

Figure 1.6 F-35 Joint Strike Fighter cockpit (1995)

Figure 1.6 shows a possible layout of the cockpit for the Lockheed-Martin F-35, the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF). The design adopts the philosophy used in the Eurofighter, but exploits recent technological progress. A single large display screen makes significantly better use of the available panel space and provides the versatility to present information in a similar way to the use of “windows” on a personal computer. It is also proposed to rely on the HMD as the sole way of projecting imagery onto the external view of the world.

1.3 Underlying factors

The condensed version of cockpit evolution given in Figures 1.1 to 1.6 fails to bring out a number of underlying threads in the mixture of engineering, human and operational factors that influence the design of cockpit systems.

The most obvious drivers have been the progressive expansion of aeronautical capabilities that have stretched the range of altitudes and airspeeds that aircraft can attain, and the improvement of avionics systems that have enabled aircraft to operate at night and in cloudy skies. There has also been the need to provide protection against modern nuclear, biological, chemical and blinding weapons. Another underlying factor is the accumulation of knowledge about human sensory, muscular and physiological limitations. This has enabled designers to arrange, for instance, that an ejection seat inflicts least injury, that displayed information can be discerned and that switches can be operated reliably even when the pilot is thrown around in a lurching aircraft.

The progressive increase in the automation of avionic systems has however exposed a profound ignorance about human cognitive limitations. The pilot of the SE5A and the pilot of the Lightning were in no doubt that their chief function was to use the throttle, stick and pedals to keep the aircraft safely aloft and on course. In contrast, the pilots of the Eurofighter and F-35 are unlikely to worry about stalling or spinning, and once airborne they will generally hand over control of the flight path to on-board automation. The role of the pilot has changed recently from that of a flier into that of a mission manager who can concentrate on understanding what is happening in the increasingly complex tactical environment generated by modern weapons and their countermeasures. However, the activities involved in flying are overt and the outcomes are measurable, whereas tactical deliberations are largely covert and the choices may not be immediately apparent. The performance of the pilot, i.e. his ability to do his job, is now less easy to assess. This has given those concerned with the design of the cockpit great difficulty in deciding whether one arrangement is better than another, and whether either is manageable. Although the human factors research community has gone to considerable effort to devise ways to measure the workload and situational awareness of the pilot, there are still no generally agreed techniques. Until human cognitive processes are understood better, engineers and regulatory authorities will undoubtedly continue to rely on the judgement of test pilots.

Another practical issue is that aircraft remain in service for a considerable period, typically forty years, often with a gradual transmutation from front line to support roles. Along with many of the mission systems and weapons, the initial configuration of the displays and controls is usually updated. Aircraft such as the Jaguar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Human Component

- 3 The Need for Protection

- 4 Crewstation Design

- 5 External Vision

- 6 The Display Suite

- 7 Display Technology and Head-Down Displays

- 8 The Head-Up Display

- 9 Helmet-Mounted Display Systems

- 10 Auditory Displays

- 11 Controls

- 12 Emergency Escape

- 13 Clothing and Headgear

- 14 Future Crewstations

- Appendix A Light and Polarisation Phenomena

- Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cockpit Engineering by D.N. Jarrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Transportwesen. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.