- 498 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Citizenship

About this book

Interest in citizenship has never been greater. Politicians of all stripes stress its importance, as do church leaders, captains of industry and every kind of campaigning group. Yet, despite this popularity, the nature and even the very possibility of citizenship has never been more contested. Is citizenship intrinsically linked to political participation or is it essentially a legal status? Does it require membership of a state, or is it only post-national, trans- and possibly supra-national? Is it a universal value that should be the same for all, or does it need to recognise gender and cultural differences? This volume reproduces key articles on these debates - from classic accounts of the historical development of citizenship, to discussions of its contemporary relevance and possible forms in a globalizing world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

The History and Theories of Citizenship – What is Citizenship?

[1]

The Ideal of Citizenship Since Classical Times

Citizens of Athens were able to represent themselves directly in their public forum. Addressing their fellow citizens in an assembly of equals, they collectively consented to “rule and be ruled.” But what of gender and matter, labour and property – the world surrounding democracy? John Pocock, addressing the Queen’s symposium on the Citizen and the State, examines the history of the public and private citizen.

WHEN WE speak of the “ideal” of “citizenship” since “classical” times, the last term refers to times that are “classical” in a double sense. In the first place, these times are “classical” in the sense that they are supposed to have for us the kind of authority that comes of having expressed an “ideal” in durable and canonical form – though in practice the authority is always conveyed in more ways than by its simple preservation in that form. In the second place, by “classical” times, we always refer to the ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean, in particular to Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries bc and to Rome from the third century bc to the first ad. It is Athenians and Romans who are supposed to have articulated the “ideal of citizenship” for us, and their having done so is part of what makes them “classical.” There is not merely a “classical” ideal of citizenship articulating what citizenship is; “citizenship” is itself a “classical ideal,” one of the fundamental values that we claim is inherent in our “civilization” and its “tradition.” I am putting these words in quotation marks not because I wish to discredit them, but because I wish to focus attention upon them; when this is done, however, they will turn out to be contestable and problematic.

The “citizen” – the Greek polites or Latin civis- is defined as a member of the Athenian polis or Roman res publica, a form of human association allegedly unique to these ancient Mediterranean peoples and by them transmitted to “Europe” and “the West.” This claim to uniqueness can be criticized and relegated to the status of myth; even when this happens, however, the myth has a way of remaining unique as a determinant of “western” identity – no other civilization has a myth like this. Unlike the great co-ordinated societies that arose in the river-valleys of Mesopotamia, Egypt, or China, the polis was a small society, rather exploitatively than intimately related to its productive environment, and perhaps originally not much more than a stronghold of barbarian raiders. It could therefore focus its attention less on its presumed place in a cosmic order of growth and recurrence, and more on the heroic individualism of the relations obtaining between its human members; the origins of humanism are to that extent in barbarism. Perhaps this is why the foundation myths of the polis do not describe its separation from the great cosmic orders of Egypt or Mesopotamia, but its substitution of its own values for those of an archaic tribal society of blood feuds and kinship obligations. Solon and Kleisthenes, the legislators of Athens, substitute for an assembly of clansmen speaking as clan members on clan concerns an assembly of citizens whose members may speak on any matter concerning the polis (in Latin, on any res publica, a term which is transferred to denote the assembly and the society themselves). In the Eumenides, the last play in Aeschylus’s Oresteia, another fundamental expression of foundation myth, Orestes comes on the scene as a blood-guilty tribesman and leaves it as a free citizen capable with his equals of judging and resolving his own guilt. It is, however, uncertain whether the blood-guilt has been altogether wiped out or remains concealed at the foundations of the city – there are Roman myths that express the same ambivalence -and the story is structured in such a way that women easily symbolize the primitive culture of blood, guilt, and kinship which the males, supposedly, are trying to surpass. But the men, as heroes, continue to act out the primitive values (and to blame the women for it).

This is a point that must be made strongly, and made all the time, but it does not remove the fact that, stated as an ideal, the community

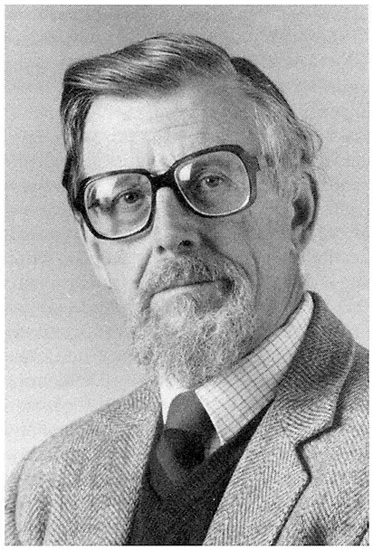

J.G.A. Pocock

of citizens is one in which speech takes the place of blood, and acts of decision take the place of acts of vengeance. The “classical” account of citizenship as an Athenian “ideal” is to be found in Aristotle’s Politics, a text written late enough in polis history – after the advent of the Platonic academy and the Macedonian empire – to qualify as one of the meditations of the Owl of Minerva. In this great work we are told that the citizen is one who both rules and is ruled. As intelligent and purposive beings we desire to direct that which can be directed toward some purpose; to do so is not just an operational good, but an expression of that which is best in us, namely the capacity to pursue operational goods. Therefore it is good to rule. But ruling becomes better in proportion as that which is ruled is itself better, namely endowed with some capacity of its own for the intelligent pursuit of good. It is better to rule animals than things, slaves than animals, women than slaves, one’s fellow citizens than the women, slaves, animals, and things contained in one’s household. But what makes the citizen the highest order of being is his capacity to rule, and it follows that rule over one’s equal is possible only where one’s equal rules over one. Therefore the citizen rules and is ruled; citizens join each other in making decisions where each decider respects the authority of the others, and all join in obeying the decisions (now known as “laws”) they have made.

THIS ACCOUNT of human equality excludes the greater part of the human species from access to it. Equality, it says, is something of which only a very few are capable, and we in our time know, at least, that equality has prerequisites and is not always easy to achieve. For Aristotle the prerequisites are not ours; the citizen must be a male of known genealogy, a patriarch, a warrior, and the master of the labour of others (normally slaves), and these pre-requisites in fact outlasted the ideal of citizenship, as he expressed it, and persisted in western culture for more than two millennia. Today we all attack them, but we haven’t quite got rid of them yet, and this raises the uncomfortable question of whether they are accidental or in some way essential to the ideal of citizenship itself. Is it possible to eliminate race, class, and gender as prerequisites to the condition of ruling and being ruled, to participate as equals in the taking of public decisions, and leave the classical description of that condition in other respects unmodified? Feminist theorists have had a great deal to say on this question, and I should like to defer to them – and leave it to them to speak about it. At an early point in the exposition of the problem, one can see that they face a choice between citizenship as a condition to which women should have access, and subverting or deconstructing the ideal itself as a device constructed in order to exclude them. To some extent this is a rhetorical or tactical choice, and therefore philosophically vulgar, but there are real conceptual difficulties behind it.

Aristotle’s formulation depends upon a rigorous separation of public from private, of polis from oikos, of persons and actions from things. To qualify as a citizen, the individual must be the patriarch of a household or oikos, in which the labour of slaves and women satisfied his needs and left him free to engage in political relationships with his equals. But to engage in those relationships, the citizen must leave his household altogether behind, maintained by the labour of his slaves and women, but playing no further part in his concerns. The citizens would never dream of discussing their household affairs with one another, and only if things had gone very wrong indeed would it be necessary for them to take decisions in the assembly designed to ensure patriarchal control of the households. In the para-feminist satires of Aristophanes they have to do this, but they haven’t the faintest idea how to set about it; there is no available discourse, because the situation is unthinkable. What they discuss and decide in the assembly is the affairs of the polis and not the oikos: affairs of war and commerce between the city and other cities, affairs of pre-eminence and emulation, authority and virtue, between the citizens themselves. To Aristode and many others, politics (alias the activity of ruling and being ruled) is a good in itself, not the prerequisite of the public good but the public good or res publica correctly defined. What matters is the freedom to take part in public decisions, not the content of the decisions taken. This non-operational or non-instrumental definition of politics has remained part of our definition of freedom ever since and explains the role of citizenship in it. Citizenship is not just a means to being free; it is the way of being free itself. Aristotle based his definition of citizenship on a very rigorous distinction between ends and means, which makes it an ideal in the strict sense that it entailed an escape from the oikos, the material infrastructure in which one was forever managing the instruments of action, into the polis, the ideal superstructure in which one took actions which were not means to ends but ends in themselves. Slaves would never escape from the material because they were destined to remain instruments, things managed by others; women would never escape from the oikos because they were destined to remain managers of the slaves and other things. Here is the central dilemma of emancipation: does one concentrate on making the escape or on denying that the escape needs to be made? Either way, one must reckon with those who affirm that it needs to be made by others, but that they have never needed to make it. The citizen and the freedman find it difficult to become equals.

If one wants to make citizenship available to those to whom it has been denied on the grounds that they are too much involved in the world of things – in material, productive, domestic, or reproductive relationships – one has to choose between emancipating them from these relationships and denying that these relationships are negative components in the definition of citizenship. If one chooses the latter course, one is in search of a new definition of citizenship, differing radically from the Greek definition articulated by Aristode, a definition in which public and private are not rigorously separated and the barriers between them have become permeable or have disappeared altogether. In the latter case, one will have to decide whether the concept of the “public” has survived at all, whether it has merely become contingent and incidental, or has actually been denied any distinctive meaning. And if that is what has happened, the concept of citizenship may have disappeared as well. That is the predicament with which the “classical ideal of citizenship” confronts those who set out to criticize or modify it, and they have not always avoided the traps the predicament puts before them. In the next part of this paper, I shall consider how some alternative definitions of citizenship have become historically available, but before I do so, I want to emphasize that the classical ideal was and is a definition of the human person as a cognitive, active, moral, social, intellectual, and political being. To Aristode, it did not seem that the human – being cognitive, active and purposive – could be fully human unless he ruled himself. It appeared that he could not do this unless he ruled things and others in the household, and joined with his equals to rule and be ruled in the city. While making it quite clear that this fully developed humanity was accessible only to a very few adult males, Aristotle made it no less clear that this was the only full development of humanity there was (subject only to the Platonic suggestion that the life of pure thought might be higher still than the life of pure action). He therefore declared that the human was kata phusin zoon politikon, a creature formed by nature to live a political life, and this, one of the great western definitions of what it is to be human, is a formulation we are still strongly disposed to accept. We do instinctively, or by some inherited programming, believe that the individual denied decision in shaping her or his life is being denied treatment as a human, and that citizenship – meaning membership in some public and political frame of action – is necessary if we are to be granted decision and empowered to be human. Aristotle arrived at this point – and took us there with him – by supposing a scheme of values in which political action was a good in itself and not merely instrumental to goods beyond it. In taking part in such action the citizen attained value as a human being; he knew himself to be who and what he was; no other mode of action could permit him to be that and know that he was. Therefore his personality depended on his emancipation from the world of things and his entry into the world of politics, and when this emancipation was denied to others, they must decide whether to seek it for themselves or to deny its status as a prerequisite of humanity. If they took the latter course, they must produce an alternative definition of humanity or face the consequences of having none. Kataphusin zoon politikon set the stakes of discourse very high indeed.

I WANT TO turn now to a second great western definition of the political universe. This one is not aimed at definition of the citizen, and therefore, in Aristotle’s sense, it is not political at all. But it so profoundly affects our understanding of the citizen that it has to be considered part of the concept’s history. This is the formula, ascribed to the Roman jurist Gaius, according to which the universe as defined by jurisprudence is divisible into “persons, actions, and things” (res). (Gaius lived about five centuries after the time of Aristotle, and the formula was probably well-known when he made use of it.) Here we move from the ideal to the real, even though many of the res defined by the jurist are far more ideal than material, and we move from the citizen as a political being to the citizen as a legal being, existing in a world of persons, actions, and things regulated by law. The intrusive concept here is that of “things.” Aristotle’s citizens were persons acting on one another, so that their active life was a life immediately and heroically moral. It would not be true to say that they were unconcerned with things, since the polis possessed and administered such things as walls, lands, trade, and so forth, and there were practical decisions to be taken about them. But the citizens did not act upon each other through the medium of things, and did not in the first instance define one another as the possessors and administrators of things. We saw that things had been left behind in the oikos, and that, though one must possess them in order to leave them behind, the polis was a kind of ongoing potlatch in which citizens emancipated themselves from their possessions in order to meet face to face in a political life that was an end in itsel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction The Importance and Nature of Citizenship

- PART I THE HISTORY AND THEORIES OF CITIZENSHIP – WHAT IS CITIZENSHIP?

- PART II RIGHTS – WHICH RIGHTS?

- PART III MEMBERSHIP – WHO BELONGS?

- PART IV POLITICAL PARTICIPATION – WHAT DUTIES?

- PART V BEYOND NATIONAL CITIZENSHIP – WHERE ARE WE CITIZENS?

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Citizenship by Antonino Palumbo, Richard Bellamy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.