Overview

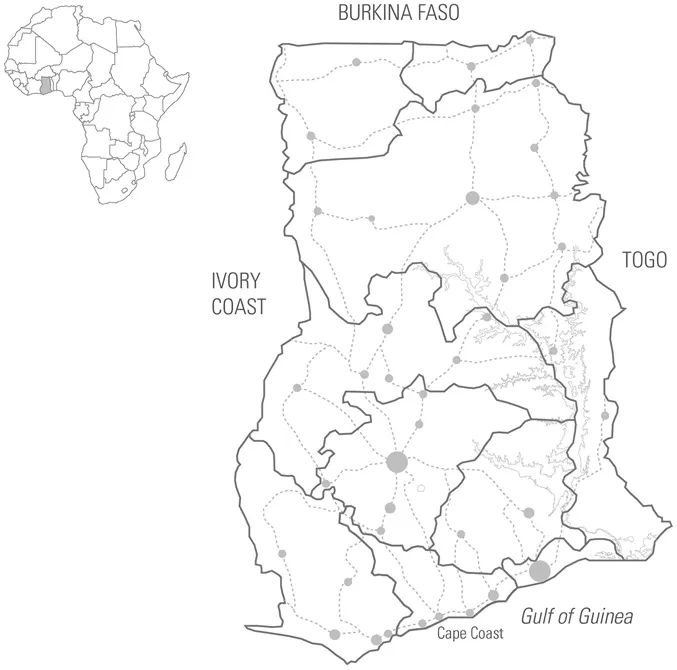

From its conceptual reinvention in the British colonial imagination in the late nineteenth century to its contemporary configurations, the Zongo is a significant and understudied network of settlements in Ghana, West Africa. Zongo means “traveler’s camp” or “stopover” in the Chadic language of Hausa and was used by British colonial officers to define the areas in which Muslims lived.1 Initially, these settlements were temporary and inhabited by Muslim-Northerners migrating south for trading purposes or as hired fighters.2 Today, however, the Zongo has become a permanent, vast network of settlements, and there is at least one Zongo in every major urban center of Ghana (Figure 1.1).

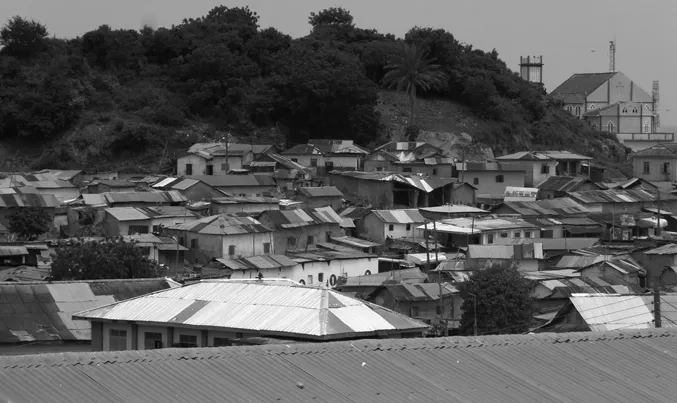

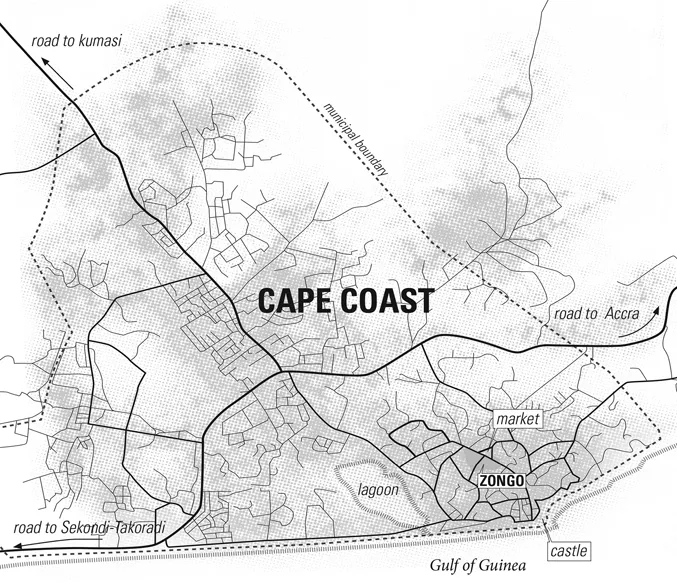

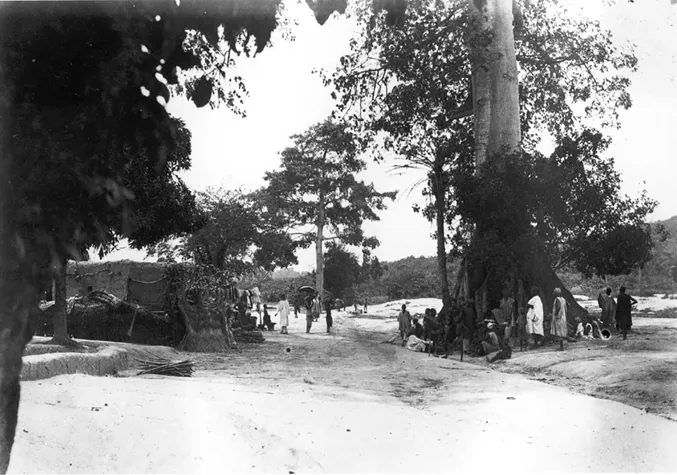

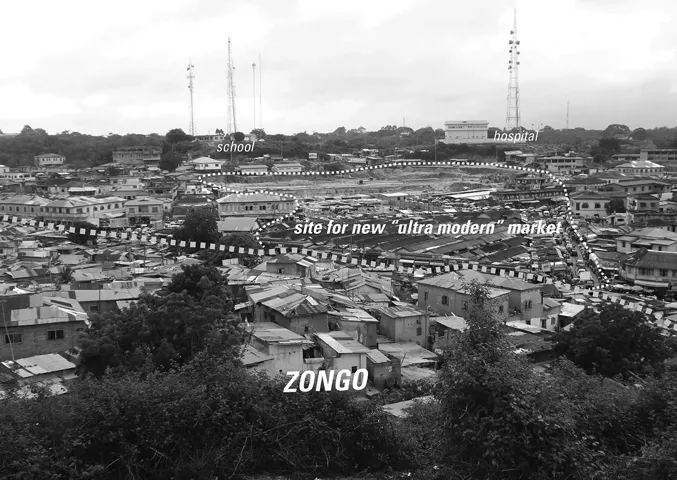

Since these ethnic groups were not indigenous to the Gold Coast, it is not surprising that many were historically marginalized. While Zongos in Ghana’s northern regions have been able to circumvent marginalization and even enjoy prosperity due to their majority religious status,3 land-based economy, and little influence from foreign authoritative powers, those further south, particularly those located along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea, still struggle to fully engage in civic life. Using history as the primary means of investigation, this research seeks to understand the Zongo’s full range of socio-spatial variation from marginalization to prosperity and the combination of historical and social factors that have caused these settlements to become relatively more prosperous or marginalized. To accomplish this, the investigation centers its inquiry on an extreme case of marginalization – the Zongo in the city of Cape Coast (Figures 1.2, 1.3).4

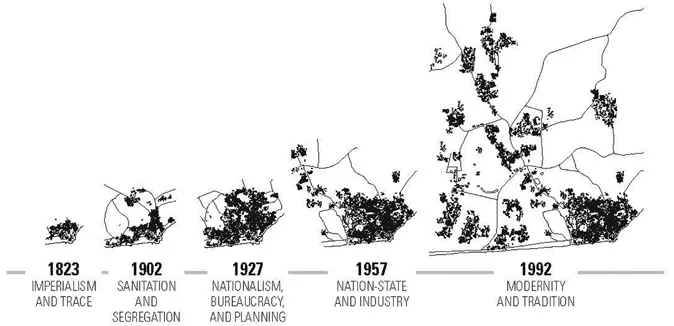

Stitching together seven years of personal experience working with the Zongo community as both designer and researcher, and primary source material from nearly two centuries (1823–2014)5, the larger body of research from which this chapter draws tells the deep and nuanced historical account of the Zongo’s socio-spatial development over five periods – each of which is a slice of time that marks important ideological and political shifts in the Zongo’s history6 (Figure 1.4).

While I tell this important history in my thesis, “Understanding the Zongo: Processes of Socio-Spatial Marginalization in Ghana”,7 the purpose of this chapter is to focus on four major themes that thread across this narrative that give meaning and relevance to understanding the Zongo beyond its locality. Prior to delving into

Figure 1.1 Zongo network in Ghana

Figure 1.2 Cape Coast Zongo urban landscape

Figure 1.3 Map of Cape Coast, Ghana

Figure 1.4 Research period timeline

these socio-spatial patterns explaining the contours of the Zongo phenomenon, however, it’s important to briefly convey how recent scholars have written about and imaged the Zongo so as to demonstrate how this research, in method and content, contributes to contemporary discourse on urban Africa.

Despite their enduring and ubiquitous existence in all of Ghana’s major cities, Zongo settlements require further historical investigation into how they engage in multi-scalar, socio-spatial processes. More often than not, scholars have tended towards representing Zongos as bounded, essentialized entities set in opposition to their local context. In an article entitled, “The Zongo Complex in Urban Ghana,” Ansu Kumar Dutta writes, “Whatever the origin, the Zongo complex in Cape Coast today bears unmistakable marks of its separateness, reflected in physical conditions, demographic structure and occupational pattern.”8 And, reinforcing the Zongo as a permanent, ossified entity, Joseph Sarfoh describes Zongos as having simply “appeared on the urban landscape.”9 While more recent ethnographies by Deborah Pellow,10 Enid Schildkrout,11 and Kelly JoAnne Tucker12 provide readers with detailed, thick, and longitudinal accounts of the community, the ahistorical accounts from geographers and ethnographers writing in the 1970s and 1980s paired with contemporary discourses on inner-city development continue to shape how scholars generalize and image Zongos today.13 Rather than classify and reduce the Zongo identity to “slums” or “ghettos” without a past,14 this research problematizes these blanket terms by contributing to understanding the Zongos’ immense variation within and between settlements, and how they shape and are shaped by the local environment of which they are an integral part.

The ambition of the themes that follow is to dismantle, complicate, and reconstruct the Zongo phenomenon – to demonstrate how it has evolved over time on spatial and social terms at multiple scales of inquiry. Furthermore, it is the hope that these themes encourage comparative investigations in Ghana and West Africa to generate a thick body of regional, critical urban theory.

A colonial religious invention

Before introducing themes focused on the Zongo’s more historical, social, and spatial dimensions, it’s crucial to first address its cultural origins as a colonial religious invention because its British beginnings have contemporary consequences. Originally a Hausa word, Zongo was cunningly retrofitted by the British as a ploy to culturally and spatially segregate Muslim-Northerners.15 Located at the margins of the town in the late nineteenth century, these settlements maintained a certain amount of political autonomy, but most importantly were rooted in collective religious belief as reinforced in photographs such as the Basel Mission’s “Mohammaden Natives” (Figure 1.5). Despite the Zongos’ evolution over the last century, its socio-spatial identity has continued to be fundamentally embedded in and built upon Islam. In contexts where Islam is in the minority, therefore, political and economic agendas, whether consciously or not, continuously re-cast and perpetuate this colonial spiritual segregation for their own ends.

Figure 1.5 “Mohammeden natives” Basel Mission Archives, 1885–1910.

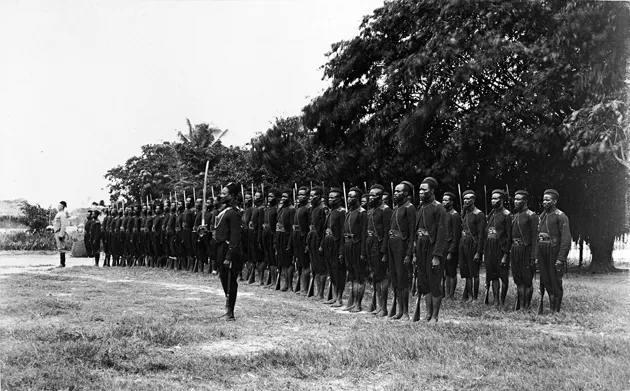

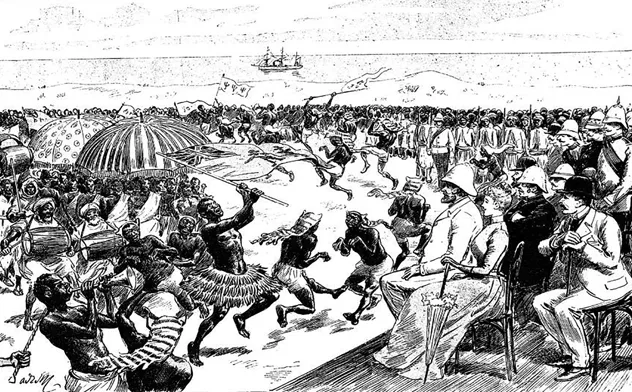

Prior to its conception and when Muslim-Northerners were still central to the British colonial agenda in the nineteenth century, their Islamic intellect and formidable strength from living on high ground were preferred over the indigenous Fante – their sinful and soggy coastal counterparts (Figures 1.6, 1.7).16 In addition, because lucrative trans-Saharan trade networks had been intertwined with Islam since its arrival to West Africa in the tenth century, the Gold Coast colony produced advertisements reinforcing their essential role in commercial success (Figure 1.8). With the dawn of a “pathological era,”17 the end of the British-Asante war in 1901, and the official establishment of the Gold Coast Colony in 1902, however, the British no longer needed the Muslim-Northerners and desired cultural segregation in the name of sanitation. As one Fante Cape Coast resident voiced,

I suppose when the segregation bungalows are completely fitted, a monster Glass Screen, miles in length and breadth, will be fixed between heaven and earth and at the segregation boundary to prevent the deadly droughts and mosquitos of the town of Cape Coast from penetrating into this novel Paradise.18

Figure 1.6 “Hausa soldiers” Basel Mission Archives, 1888.

Figure 1.7 “Reception of the governor of the Gold Coast” The Illustrated London News, August 23, 1890, Issue 1082.

Figure 1.8 “Cracker sifter trademark” The Gold Coast Times, October 1, 1881.

Figure 1.9 “The church, Cape Coast, opposite the castle” Basel Mission Archives, 1885–1910.

Figure 1.10 “Road to Kotokuraba (Hausa Town)” Basel Mission Archives, 1885–1910.

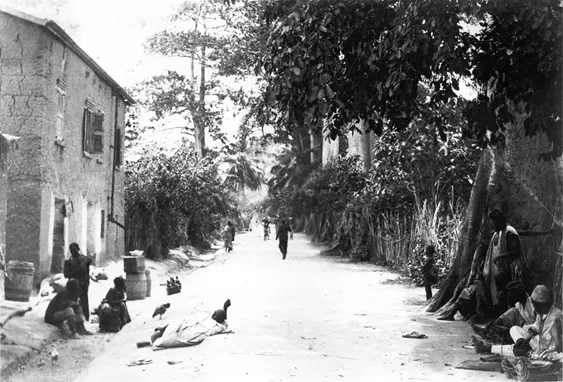

Where native and European beliefs and spaces converged, however, was at the church, the lungs of the city (Figure 1.9). This shared space became the center for not only religious education but also training in agriculture that simultaneously planted the seeds of nationalism.19 Rather than encourage integration, the British awarded the ex-Hausa soldiers a swampy part of Kotokuraba they christened Zongo (Figures 1.10, 1.11).20 As one of the Zongo residents explained, “The place they gave us was a thick bush densely populated by spirits. We had to call upon an Islamic scholar to prepare religious rituals to chase them away.”21 For both the British and Zongo, therefore, religion became the foundation and authority of the settlement.

Figure 1.11 “Part of Kotokraba” Basel Mission Archives, 1885–1910.

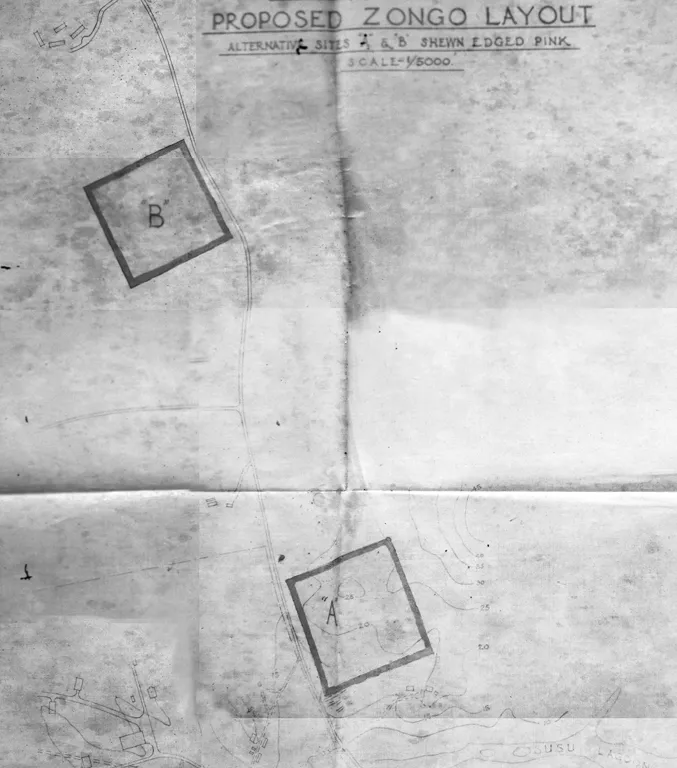

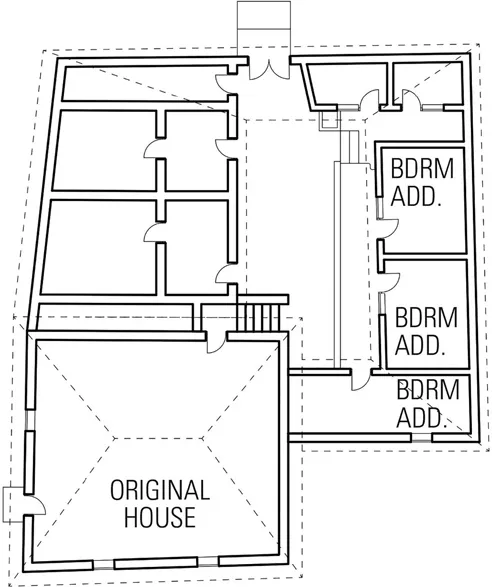

In the subsequent period, 1927–1956, Zongos became increasingly marginalized due to new visions for a comprehensive town planning scheme that introduced rigid building regulations without accommodating Muslim needs and even threatened to move them outside of town (Figure 1.12).22 These new policies caused increased friction by zoning areas “Zongo”23 only within which residents were permitted to generate visual expressions of faith such as murals, participate in religious ceremonies, and practice Islamic laws of land inheritance by adding bedrooms for children, grandchildren, and tenants to the original house (Figures 1.13 – 1.15).24

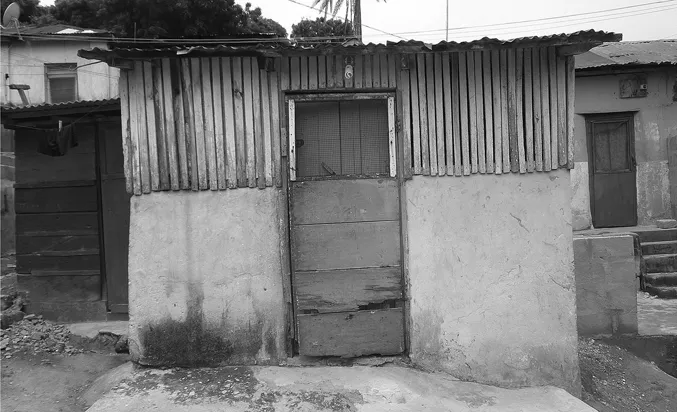

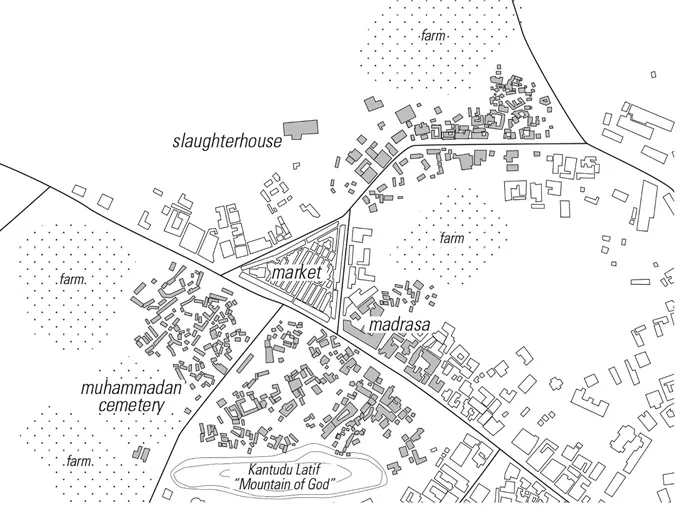

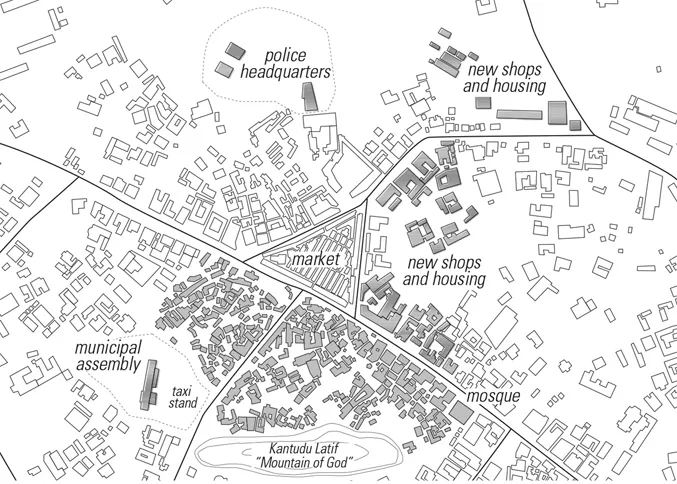

Despite the socialist agenda installed after independence in 1957 banning the formation of groups based on religion or ethnicity, the nation-state still sponsored the Zongo’s spiritual segregation, but under a political and social guise (Figure 1.16). Whereas before independence the settlements still maintained farms, slaughterhouses, Madrasas, and a Muhammaden cemetery in areas orbiting Kotokuraba market, after independence, these religious and cultural spaces were perceived as “foreign” and demolished in favor of a new municipal assembly building, police headquarters, shops, and housing (Figures 1.17, 1.18). Whereas before, the Zongo residents had relied on spaces external to their domestic arena for religious practices, during this period, Islam became increasingly internalized as residents constructed four new mosques25 within the boundaries of the settlement and converted alleys, porches, and open areas into spaces for learning the Quran, prayer, and ablution (Figures 1.19, 1.20).26 Thus as Zongo space became more sanctified, it also became less associated with institutions and other civic spaces outside of it.

Figure 1.12 Komenda: “proposed Zongo layout” Cape Coast Regional Archives.

Today, spiritual segregation has been reproduced through the binaries of modernity and tradition. Just as modernity and Christianity have come to define the areas outside the Zongo, tradition and Islam have become its necessary complements inside (Figure 1.21). As Dell Upton elucidates, “Tradition did not exist until it was imagined as the defining complement of modernity.”27 One Cape Coast resident

Figure 1.13 Mosque and the Ka’ba mural

Figure 1.14 House floor plan

Figure 1.15 House room addition

Figure 1.16 Kwame Nkrumah shaking hands with Muslim leader

Figure 1.17 Map of Kotokuraba before independence

Figure 1.18 Map of Kotokuraba after independence

Figure 1.19 Mosque in the Zongo

Figure 1.20 Hassaniyya Quranic school

voiced his own hopeful, yet ironically tragic, interpretation of Zongo. He explains that Zongo is not a place at all.

It means transit, to travel, to not always stay in one place. It is actually not a Hausa word. ‘Zon’ means to come in Hausa and “Go” means “I go” in English. It means we come and go as we please.28

Figure 1.21 New construction at Kotokuraba market

Despite the resident’s emboldened vision of a Zongo that has been able to break away from its colonial maker, it reasserts, both linguistically and conceptually, the Zongo’s origins in, and entanglement with, its colonial past. This struggle, sometimes more conscious than others, is a theme that will re-emerge in the findings that follow.

No matter the period, therefore, the Zongo’s identity is defined by a colonial invention soaked in traditional Islamic beliefs. It maintains an underlying structure that relies upon both Islam as its fundamental socio-spatial organizing principle and a culture of difference having been planted in the region by British colonialism. In understanding and making visible these cultural forces that at times impede and other times enable the Zongo settlement, one may then adapt and apply the lessons and methods from this study to other minority Islamic settlements in West Africa. Furthermore, and on a global scale, the research contributes to conversations concerning the welfare of other minority Islamic settlements with similar colonial foundations.