![]()

Chapter 1

Science and behaviour

One of the most obvious qualities of animate creatures is that they behave; they do things that change their relationships with the objects about them, whether these other objects are themselves animate or inanimate. Such activity, this doing, provides a subject of study for psychologists and for this book. In the pages that follow, an attempt is made to consider some aspects of behaviour according to specifiable scientific principles. This preliminary chapter provides a brief history of how these principles have evolved in the study of behaviour.

Perhaps the most basic characteristic of science in general is that it organizes and develops our knowledge of the world in which we live. This is achieved by asking questions of nature, by investigating observable phenomena. At one level, such attempts to organize our knowledge may entail no more than an agreed description of the subject being scrutinized. Some may recall zoology lessons at school for apparently endless descriptions and classifications of all manner of animals. In a behavioural science, too, descriptions such as these are of the utmost importance. They are also often fascinating, as evidenced by the popularity of naturalists' films showing the behaviour of animals in their natural environments.

Behaviour, then, is the activity of animate creatures, and psychology the study of this activity. However, even the first step, describing behaviour objectively, may soon encounter difficulties. Some of these are obvious enough, not least the problems of measuring behaviour in some reliable way. But confusions may result even from the simple notion that activity provides the basis for distinguishing what we regard as animate creatures from inanimate objects. For example, one creature which is accorded the rank of animal by zoologists suffers the indignity of being likened to a plant in its popular name — the sea anemone. This apparent inconsistency may result from the fact that its repertoire of behaviour is exceedingly limited; it does few things which will interest a human observer. Its sedentary existence seems uninspired, and it might be argued that its sharing of a name with the beautiful, but admittedly inanimate, woodland anemone is as much as this creature deserves. Yet zoologists could affirm that the sea anemone deserves the more exalted rank in man's affections, because, after all, it is an animal. On the other hand, some plants, at least in terms of botanists' classifications, have traditionally exerted a degree of fascination for man, because they seem to behave like animals in some respects. Perhaps the best known example of such a plant is Venus's Flytrap, to which is sometimes attributed the sinister motive of hatching a plot to ensnare its unsuspecting prey because of the relatively sudden movements of the plant which trap an insect.

Although we spend so much of our time in the company of other behaving creatures, it seems that we rarely stop to think about the defining characteristics of behaviour. If it is accepted that one of the primary tasks of psychology is to describe behaviour, which events qualify for the use of that word? Does the sea anemone behave? Does Venus's Flytrap? At first sight, the activities of the latter seem to offer the more likely events for an appropriate use of the term. However, we may wish to revise our opinion when confronted with the authoritative statements of zoologists and botanists, which are, of course, based on criteria other than what the sea anemone and Venus's Flytrap do. We may now prefer to use the term behaviour to describe the apparently aimless flutterings of the sea anemone's peripheral parts, but describe the more striking movements of the plant as behaviour only in a metaphorical sense: perhaps we were misled by the apparent purposefulness of the Flytrap, because when we are told that we are observing a plant our view changes. Our criterion for judging an event as behaviour, then, seems to depend not merely on its complexity: the reasons for the occurrence of these events are also taken into account. Here perhaps lies the fascination shown by Victorians for automata. The monkey sitting on the mantelshelf may move his hand to his mouth, puff at the cigarette held in it, and then move his head to one side and close his eyes for a period before beginning the cycle again; in the Victorian drawing-room this has many of the characteristics of 'real' behaviour and apparently reflects satisfaction and purpose. However, this is not 'real' behaviour, for it is merely the result of a clockwork mechanism within the automaton.

Clearly we have taken the decision to reserve the appropriate use of the word behaviour to living animals (including man). Plants, automata, machines, may appear to 'behave', but use of this word is merely to indicate an analogy between their activities and the behaviour of animals. The difference between them lies in the reasons for the actions in all these cases. In a sense, this decision reflects the influence of our culture and of science upon us. We live in an age that emphasizes man's responsibility for his own actions, but in one that has also been dominated by the progress of science. In the recent past man has organized his knowledge of the world about him ever more effectively, and has thereby produced an accompanying increase in the speed with which new knowledge has developed. This has particularly been the case with the so-called physical sciences, such as chemistry. Our knowledge of inanimate objects studied by such physical sciences is now so great that we are able to change our world radically to our own advantage, if we can prevent ourselves from using our understanding to our own profound disadvantage. The methods of the physical sciences are now also being applied more and more effectively in studies of living creatures, as evidenced by the increasing impact of such disciplines as biochemistry and physiology. This rapid increase in our understanding and control of the world has depended to a large extent on the abandonment of previous explanations for the metaphorical 'behaviour' of physical events.

There was a time when all phenomena in the world about man were explained by him in terms of spirits or forces 'inside' these observable occurrences. Such a view is termed animism. The internal spirits were not open to the direct inspection of mere humans, but by assuming that they existed it became possible to 'explain' all the phenomena that were seen to occur in the physical world. For example, it might be considered an adequate explanation for the fact that a stone rolled down a hill to assert that it was motivated to do this by a propensity to approach the centre of the earth; this motivational force, vis viva, impelled the stone to move. Stones and waterfalls, trees and clouds, the wind and the sea: the actions of all these were once interpreted by appeal to internal spirits which motivated them to behave in the ways that were observed. Nowadays we recognize that such an explanation is not the most useful in our attempts to organize our knowledge. In order to make the stone roll, or to stop it, we attend not to its internal motivations, but rather to our knowledge of observable events which have previously led to such occurrences. This knowledge is summarized in our description of the world in terms of scientific laws, the power of which makes it seem unnecessary to seek an explanation of an animistic kind. Similarly, with the organized knowledge of science we do not need to explain the 'behaviour' of the monkey automaton in terms of its internal motivating spirits; nor does an appeal to such unobservable forces in the Venus's Flytrap help us to explain its 'behaviour' more satisfactorily.

In spite of this scientific movement away from animism in our considered explanations of physical events, in our everyday language we continue to use expressions that imply that we still believe in animistic explanations. Our language frequently continues to attribute animistic feelings to inanimate objects: the sea rages, the sky is gloomy or cheerful, the weather mischievous. In using such language we undoubtedly enrich our vocabulary and add emotive quality to our lives. Perhaps this is the reason why, for example, many people feel great sadness when a majestic tree is felled. The point is made even more noticeable by the fact that poetry is often perfused with animistic language.

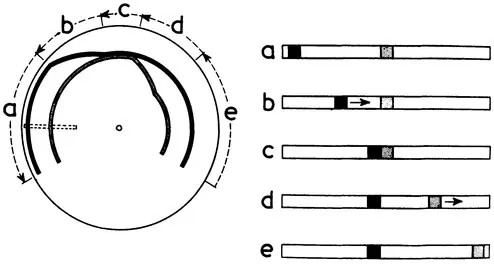

The use of quasi-animistic language in everyday conversation is certainly no bad thing on the whole. However, there is some danger that animistic concepts may even now colour our appreciation of the physical world more than we ordinarily recognize. A possible example of this is to be found in one of the most fundamental concepts which we use, that of causality. In a well-known series of experiments, Michotte (1954) studied this concept by using the simple apparatus shown in Figure 1. Two thick lines were drawn on a cardboard disc, which could be rotated about its centre in a vertical plane. Between the subject and the disc was mounted a large shield, in which was cut a horizontal slit. The subjects could see small portions of the two lines through this slit. By rotating the disc, Michotte made these two squares of line appear to move along the slit, these movements being governed, of course, by the curves of the lines themselves. On the left of Figure 1, one of the patterns used by Michotte is shown, and the letters round the periphery show the five separable stages induced by rotating the disc counterclockwise. The right section of Figure 1 translates these five stages into what can be seen through the slit in the shield. At first (a) the black and the grey squares are both at rest; then (b) the black square appears to move along the slit towards the grey. For a brief period (c) the two squares are touching but not moving. Then (d) the grey square moves off away from the black, and eventually (e) comes to rest.

Figure 1 The disc rotated in Michotte's experiments (left), and the sequence of events seen through the slit by an observer. After Michotte (1954).

Michotte investigated a number of variations on this basic procedure, but these are not important here. The major finding of the series of experiments was that the subjects reported that the black square caused the grey to move. This observation may be expressed in various ways: black makes grey move, black pushes grey, grey is forced to move, or grey has to move in these circumstances. Another common description is that the grey square moves because of a transfer of a force of motion from black to grey. Expressions like these are common as attempts to convey the concept of causality in other contexts too. Michotte's procedure, however, really amounts to an illusion, because, of course, the movements of the black and grey squares are determined merely by the curves of the black and grey lines on the rotating disc. Yet, a simple report of what is actually seen (as throughout the five parts of the sequence outlined above) seems to the observers to be inadequate as a description of what they think they see. This may be because the verbal expressions used to convey causality almost all contain the ghosts of animism; they are verbal remnants of the time when animism was taken to be a literal explanation for observable phenomena. We are so accustomed to using these animistic remnants in everyday language that we feel deprived of 'explanatory' power if we are forced to remove them and report merely what is observable rather than inferable. A factual language which is studiously non-animistic often seems to be stripped of explanatory power; we feel that we mean more than this, but we are unable to say what this extra is.

It would seem, then, that science does not use animistic explanations for physical events, although some aspects of animistic thought have been retained in our everyday language. Non-animistic reasons are now also sought for events in the physical systems of living plants and organisms. Reliance on animistic explanations may even be said to be pre-scientific. We have also seen that we reserve the appropriate use of the word behaviour to the activities of animals, and that psychology is the scientific study of such activities. The question now arises: should psychology rely on animistic explanations of behaviour? On the basis of the preceding discussion, some might wish to be brave and answer in the negative, arguing that psychology should follow the path of the established sciences. However, the question is not an easy one to answer. The very etymology of the question emphasizes the potential difficulties and confusions here: is animism appropriate for animal behaviour? In one sense, we have perhaps already answered the question with a muted affirmative in this chapter by distinguishing the activities of the sea anemone and Venus's Flytrap in a counter-intuitive way, based not on the complexity of the activities, but on the nature of the organisms. May this not be essentially animistic? The truth of the matter is that most of us do use animistic explanations quite seriously in order to explain our own behaviour. Our activities are said to reflect the motivating influences of an inner spirit which is not open to direct observation by others; our behaviour is therefore explained by reference to this inner self. The inner man wants and the outer man acts.

In considering the difficulties of explaining human behaviour, it is unusually instructive to consider the historical development of man's attempts to explain the behaviour of infra-human species. Many owners of pets would today think it execrable if one were to suggest that their dogs' and cats' behaviour might be 'scientifically' explained without ultimate reference to their internal motivating spirits. But as long ago as the seventeenth century, the philosopher Rene Descartes was offering just such a possibility — that the behaviour of animals should be explained mechanistically, without recourse to their inner selves. Descartes may have been led to such an opinion in part by an acquaintance with automata similar in concept to the Victorian monkey mentioned earlier. At that time, the Royal Gardens at Versailles, as elsewhere, were ornamented by a number of mechanical figures in the form of animals or people. These were operated hydraulically, their mechanisms being activated by pressure on platforms concealed in the footpaths of the gardens. Thus, a romantic stroll might be unexpectedly interrupted by sudden bodily movements or sounds on the part of the garden furniture, sometimes of a singularly unromantic nature. Such an experience must have been disarming, but nevertheless fascinating. Descartes argued that it was possible to regard humans and animals as mechanical systems analogous to, but more complex than, these hydraulic models. Their movements, he considered, are not the result of water being pumped into the limbs, but nevertheless may be produced by an essentially similar system which transfers some as yet undiscovered substance to the muscles. Descartes suggested, for example, that inadvertently placing a hand in a flame would result in the heat exciting a nerve to the brain, which then automatically pumped animal spirits to or from the arm muscles; these caused the muscles to expand or contract, and thereby removed the hand from the flame. Notice that Descartes's invocation of animal spirits in this context is not the same as the doctrine referred to as animism above, for he did not argue that these spirits initiated action; they merely reacted in a mechanical way to other events. Although Descartes attempted to explain certain patterns of involuntary behaviour in humans in this way, it was most certainly not his purpose to explain all human behaviour mechanistically. Indeed, one of the most important and pervasive aspects of his philosophy was his unshakable belief that man is more than a mere physical system; man also had a rational soul which chose to initiate voluntary, non-automatic patterns of behaviour. This soul was thought to be immortal and intangible, not subject to mechanistic explanations, and therefore animistic in the general sense. It resided within the mechanical system of the body, whose behaviour it could initiate and direct through the pineal gland. Of particular interest in the present context, however, was Descartes's preparedness not to attribute such a soul to animals, thereby suggesting that animals were merely very complicated machines whose behaviour was therefore to be explained in purely mechanistic terms. Such an account deprives animals of all volitions as such, their behaviour being simply the reactions of their bodies to their environment. This in no way denigrates the complexity of some patterns of animal behaviour. On the contrary, Descartes was quite prepared to admit that animals may do some things better than humans; however, such complex behaviour is nevertheless to be regarded as 'nature working in them according to the disposition of their organs' (Discourse on Method; 5), that is to say, mechanistically.

Descartes' distinction between the fundamental natures of animal and man is probably not unattractive to man himself. However, confidence in this division was severely tested in the nineteenth century by Darwin's publications on the evolutionary process. The general impact of this theory was enormous, and needs no emphasis here. However, it is important to notice that any scheme which stresses the continuities between species, including man, inevitably makes it more difficult to maintain fundamental distinctions between man and animals in the way suggested by Descartes. Darwin himself published a book in 1873 entitled Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals, in which he produced a great number of comparisons between the behaviour of man and of animals within an evolutionary context. For example, he suggested that the curling of our lips when we sneer is a relic of the baring of canine teeth in rage shown by carnivorous animals. In extending the evolutionary argument to behaviour Darwin may be said to have initiated an approach to the study of behaviour which is now enjoying something of a vogue, to judge by the current popularity of the writings of Desmond Morris (e.g. The Naked Ape, 1967) and Robert Ardrey (e.g. The Social Contract, 1970).

Faced with Darwin's publications, subsequent writers adopted one of two possible reactions (both of which may still be detected in the present reactions to the publications of Morris and Ardrey). One might decry the attempt to debase man's nature, an attitude motivating Bishop Wilberforce's famous taunt that T. H. Huxley should declare whether it was through his grandmother or his grandfather that Huxley claimed his descent from an ape. To adopt this strategy makes it easily possible to maintain a Cartesian view of man and animals, by denying vigorously that man can be regarded as no more than a complex machine. However, in the context of behaviour, it is interesting to discover that the alternative position was advocated by some. It is well understood, the argument went, that man is endowed with great intelligence and many moral virtues; therefore, if evolutionary theory is accepted, these characteristics will have evolved through the species in the same way as did man's physical characteristics. It subsequently follows that some species of animals may be pretty intelligent too, and, what is more, moral virtues might be detectable in them. Such an idea was taken up by many gentlemen of the era, and in the true tradition of Victorian amateurism, the hunt for animal virtues was joined. Examples of reasoning, of self-sacrifice, of self-control and of public-spiritedness were sought in the humblest of creatures, often with apparent success. Much of this work was reviewed and summarized by Romanes in a book entitled Animal Intelligence (1882), a treatise which it would be difficult to better for entertainment value and for its reassuring view of nature. However, most of the evidence reported did not rest on the detached objectivity which is demanded by science. It was difficult to distinguish what in fact had been observed from the interpretations of behaviour. Untrained observers tended to seek the greatest possible virtue from the simplest patterns of behaviour. In short, much of the evidence for animal virtues was no more than anecdotal, and most interpretations of animal behaviour was blatantly anthropomorphic. Inevitably, a reaction, summarized by Lloyd Morgan, eventually set in to this profligacy. He argued that we should interpret animal behaviour as parsimoniously as possible: 'In no case may we interpret an action as the outcome of the exercise of a higher psychical faculty, if it can be interpreted as the outcome of the exercise of one which stands lower in the psychological scale.' (1894).

The current interpretation of animal behaviour would seem to endorse Lloyd Morgan's strictures. Scientific reports of animal behaviour abound, but, in these at least, psychical functions are rarely mentioned. One might rephrase this comment by saying that a science of animal behaviour has developed which is careful to avoid animistic explanations. Behaviour is described precisely, in terms of when and where it was observed. Explanations for behaviour patterns may be offered in terms of their supposed evolution within a species (because of evolutionary pressures similar to those selecting taxonomic form) or their development within an individual (by means of learning processes to which that individual has been exposed). The wants and desires of the inner animal are conspicuous by their absence in these reports, being replaced by less abstract descriptions of the behaviour actually observed or occasionally by references to physiological investigations. This is not to deny that colloquially it is usually simpler to use relatively animistic terms to explain the behaviour of animals. It will always be simpler and more elegant to descr...