- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book deals with specific issues of the characteristics of various chronic pediatric diseases that cause stress for these families in their coping processes. It emphasises on the changes in the coping system.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Theory of Coping Systems by Francis D. Powell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

CHANGE WITHIN COPING SYSTEMS

I-1. Supportive Coping Systems1

Coping systems are social networks which deal with stress-producing long-term problems; they deal with these problems by means of available resources. Supportive coping systems are social networks in which primary responsibility for dealing with problems is assumed by the problem bearers themselves. Resocializing coping systems assign primary responsibility for dealing with long-term problems to assisting specialists.2

Supportive coping systems are, for example, family and staff networks of probation departments, open prisons, halfway houses, therapeutic communities, drug institutes, community mental health centers and after-care programs which cope with long-term stress through social support.3

Resocializing coping systems include maximum security prisons, custodial mental institutions, tuberculosis hospitals, detention camps, reform schools and military academies. Insofar as such programs minimize the use of the resources of those immediately confronting the problems, they are deficient as coping systems.

An important type of supportive coping system is concerned with the care of children. Families are confronted with problems of their mentally retarded or physically handicapped children. Minority group children who are targets of broad societal prejudice or disprivilege are faced with a range of difficulties. Certain flexible educational institutions and neighborhood youth centers provide support to the primary resources of families and communities in coping with these difficulties.4

A unique variety of coping system involves families dealing with the stress of chronic children's illness. Such families avail themselves of the services of ambulatory pediatric departments while assuming primary responsibility themselves for the child's care. The characteristics of various chronic pediatric diseases pose specific issues of stress for these families in their coping processes, and it is some of these specific issues that we shall deal with in this book.

Children with diabetes must from an early age assume autonomy in understanding and managing the condition. The principal responsibility for this autonomy training rests with the family. The unusual demands placed upon the child and the family is a cause of long term stress. The pediatric staff, in its secondary capacity, attempts to provide appropriate support to families coping with these problems.

In chronic pediatric arthritis, the uncertain and degenerative nature of the illness requires dependency and trust in medical judgment. Family responsibility for primary ambulatory care thus revolves around the issues of dependency on the hospital in making treatment changes and of family acceptance of the long-term incurable illness. This acceptance and trust is supported through a responsive and emotionally channelled staff-family relationship.5

With the hereditary fatal illness of cystic fibrosis long-term grief, guilt and ambivalence are major stress producing forces. Ritualized exchanges between staff and families reinforce the family process of coping with these forces and with the intermittent despair that accompanies them.

I-2. Dynamic Factors in a Supportive Organization

The physical setting for staff-family contact within a supportive institution serves to reinforce the character of family management of various illnesses. Thus, in the context of ambulatory outpatient services, waiting room contacts between staff and families are used to foster family autonomy in the home related aspects of the illness. On the other hand the intimacy of the examination room is often used as a setting to support families’ need for dependency and acceptance of illness.

Coping systems are characterized by the looseness of their boundaries. Not only do “boundary spanning” personnel6 such as nurses reach into communities to provide support, but family networks penetrate the helping institutions to negotiate for satisfaction of their needs. Owing to uncertain technology, diffuse need and capricious political status, staff and families mingle as definers and providers of the help that is required to deal with long term stress.7 Through this sensitive, focused process the resources of family and community networks are brought to bear on these long term problems.8

The emotional interplay between family members and helping personnel is an important aspect of social support. Among the patterns isolated in this interplay, affective channelling and affective restraint figure prominently.9

The empirical focus of the present research is the interaction of families and staff in a health organization serving as an agency of support for families with chronic pediatric health problems. A number of children's ambulatory health services provided a context for the study of families and staff and their related community network resources.10

I-3. Setting for the Study of Change

This analysis is based on research conducted at a large metropolitan pediatric hospital.11 The data was drawn primarily from transcriptions of tape recordings of interactions between clinic nurses and families in four pediatric outpatient services: arthritis, diabetes, orthopedics and cystic fibrosis. The recordings were made by nurse observers during two periods of two weeks each. While recording verbal exchanges the observers noted the presence of hospital personnel, patients and family members, and checked the location and time of each interaction. Recorded interviews and informal conferences were held with clinic nurses and physicians and supervisory staff, who were asked to describe their roles and the problems that tended to arise in the clinics. These meetings along with the direct observations of research staff members were useful in interpreting the recorded data.12

During the period of study the outpatient department moved from an old small building, to new and expanded facilities with additional medical areas and large comfortable waiting rooms. With the move, additional clerical and nursing personnel were introduced to assist staff members in administrative and technical duties. In some instances the staff of physicians was also augmented. The first wave of observations was made just prior to the move from the old facilities, and the second took place seven months after the move. These observations have been supplemented by interviews and informal contacts with the clinics over a period of years. Follow-up contacts tend to substantiate the continuity of change in health service observed in connection with this organizational restructuring.

I-4. Nursing Focus and Coping Systems

Although the data from the outpatient departments included interactions with physicians and other members of the staff of the outpatient departments, the principal focus was the interaction between nurses and families. The broad range of roles involved provided a basis for the analysis of the outpatient services as coping institutions.

The centrality of nursing behavior in the data was useful as a means of gauging change in the outpatient clinics viewed as supportive institutions within coping systems. This research and parallel studies suggest that clinic nurses, social workers and community trained personnel are best equipped to support family coping processes; they are more identified with the personalized needs of families or communities,13 than are neutral value-oriented, specialized autonomous professionals.14 Physicians, institutionally backed bureaucrats and academically trained behavioral science practioners, often have a professional incapacity for dealing with long range stress problems. The psychoanalytic “hour” is one classic example of a rational approach to the non-rational needs characteristic of long range situations. But nurses and social workers, though inspiring a lower level of expectation through a more muted image, are more generally in tune with the problems confronted by coping systems.15

The aptness of particularistic, non-autonomous professionals such as nurses and social workers for supportive roles within coping systems, suggests a social variance rather than a social deviance model for such systems.16

The families involved in the present research appear to have coped more by varying in relation to accepted social norms than by deviating from these norms. Families with chronically ill children vary by assuming different life styles through hyper-individuation, rather than by directly challenging relevant social rules.17

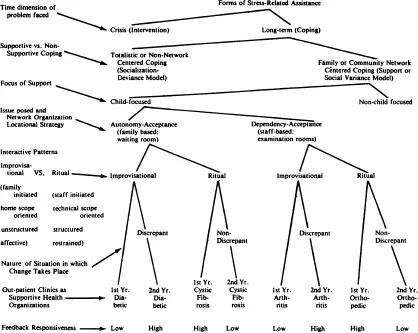

I-5. A Typology for Analysis of Change

The analysis is based typologically on support settings which are either unicentered or polycentered. Unicentric settings highlight staff-based areas, while polycentric settings encompass both staff and family areas, and are designated as family-based. The typology is also differentiated in terms of ritual and improvisational interactive patterns.

From these locational and interactive components we derive four types of supportive coping organizations: staff-based improvisational, family-based improvisational, staff-based ritual and family-based ritual organizations.18 Each corresponds empirically to one of the four outpatient clinics explored.19

The establishment of a basis for the interpretation of change within coping systems is a main interest in this typology. Health services characterized by improvisational interaction adapt more readily to increased bureaucratic complexity and to change in the institutional setting; those with ritual patterns are disrupted by such alterations. Institutional discrepancies foster the emergence of improvisational patterns of interaction. Improvising support systems in turn make use of such discrepancies to adapt positively to change. (See Figure A-I-5 for a schematic analysis of change in supportive coping systems.)

FIGURE A-1-5

SCHEMA FOR THE ANALYSIS OF CHANGE WITHIN COPING SYSTEMS

SCHEMA FOR THE ANALYSIS OF CHANGE WITHIN COPING SYSTEMS

1 This discussion of types of coping systems parallels somewhat the approach of Glaser and Strauss. Cf. Barney G. Glaser and Anselm L. Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1967.

2 Coping systems take on the characteristics of the institutions serving them. Thus families and communities coping with long-term stress with the help of supportive institutions are designated as supportive coping systems. Families and communities coping with long-term stress with the help of resocializing institutions are designated as resocializing coping systems.

Aspects of the present discussion are based on Wheeler's analysis of formal socialization organizations. Cf. Stanton Wheeler, “The Structure of Formally Organized Socialization Settings,” in O. Brim and S. Wheeler, Socialization After Childhood: Two Essays, New York: John Wiley, 1966.

3 For a closely related analysis of institutional concern with long-range issues cf. M. Lefton and W. R. Rosengren, “Organizations and Clients: Lateral and Longitudinal Dimensions,” American Sociological Review, XXXI (December, 1966), pp. 802–810.

4 Network coordination between supportive institutions within the community is documented in the present research. Cf. below V-5 through V-9.

5 These tendencies accord with Mills’ observations on the group process of “rechannelling energies and feelings associated with interpersonal relations into the collective spirit.” Cf. T. M. Mills, The Sociology of Small Groups, Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall, 1967, pp. 83 ff.

6 James D. Thompson, Organizations in Action, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967.

7 The coping systems approach adopts a cultural point of view somewhat parallel to that of functional theory. However, contemporary institutions assume a mechanistic and individualistic design in terms of contractual, short-run relationships. The fact that human experience is not lived discretely and individualistically but continuously and socially, brings families into conflict wit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Change Within Coping Systems

- Chapter 2. The Arthritis Clinic: A Staff Based Improvising Organization

- Chapter 3. The Arthritis Clinic: Change in a Staff Based Improvising Organization

- Chapter 4. The Diabetic Clinic: A Family Based Improvising Organization

- Chapter 5. The Diabetic Clinic: Change in a Family Based Improvising Organization

- Chapter 6. The Orthopedic Clinic: A Staff Based Ritual Organization

- Chapter 7. The Orthopedic Clinic: Change in a Staff Based Ritual Organization

- Chapter 8. The Cystic Fibrosis Clinic: A Family Based Ritual Organization

- Chapter 9. The Cystic Fibrosis Clinic: Change in a Family Based Ritual Organization

- Chapter 10. Implications and Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Appendix A. Methodology

- Appendix B. Tables

- Appendix C. Instruments

- Index