![]()

1. Setting the Scene

Introduction

There are many excellent books which discuss the concept of knowledge management in detail. The aim of this publication is to provide some practical guidelines for those interested in, or likely to be involved in, the implementation process and the subsequent knowledge management operation, whatever their current role. Some discussion of the subject does take place to put it into context; definitions are given and references made to key works in the field, along with suggestions of additional sources to consult. Questions to be addressed and issues to be considered are put forward. Case studies have been produced to illustrate different aspects of implementation and operation. Contact details of organisations and individuals who might assist further are also listed. It is hoped that this approach will provide a helpful starting point for those taking part in the development of a knowledge management function.

What is knowledge management?

Two of the most frequently asked questions about the subject of knowledge management seem to be "What exactly is it?" or alternatively "Is it a new name for information management?" Information is not a synonym for knowledge, which is an intellectual concept, referring to the condition of knowing or understanding something. Bonaventura (1997) suggests that neither data nor information on their own should be regarded as knowledge. He says that "Rather information is the potential for knowledge" noting that information will have to be worked upon, developed and applied; thus "Knowledge then, can be considered as output(s) from a continuous feedback loop which refines information through the application of that information."

In a discussion about information and knowledge Badenoch et al.(1994) note the difficulty of defining knowledge, saying that "many different disciplines use the term to denote different things". They see knowledge as being "personal, individual and inaccessible" which could make it difficult to harness; but they go on to say that "it does, however, manifest itself in (and is created and modified by) information". They also describe knowledge as a "dynamic, self-modifying state" which "changes in the course of acquiring information". This demonstrates the close relationship between the two concepts and why the terms which describe them are sometimes used interchangeably. In seeking definitions of both knowledge and information Badenoch and his colleagues consulted key sources in the field and found what could be the simplest definition of all: that knowledge is "organised information in people's heads", Stonier (1990).

Various terms are used to describe what are seen as different types of knowledge. The two most commonly referred to in the business context are "explicit" and "tacit" knowledge. According to Nonaka & Takeuchi (1995) explicit knowledge can be articulated in formal language and transmitted through, for example, manuals, written specifications etc. Tacit knowledge is seen as personal knowledge, based on individual experience and values and therefore not as easily transmitted. However once the sharing of tacit knowledge has become part of the corporate culture, and it has been harnessed accordingly it will not be lost to the organisation if a particular individual moves on. By then it will have become embedded in the organisation as noted by Badaracco (1991). A practical example of the way in which knowledge might not only become embedded in a single organisation, but also have the potential to be organised to be accessible more widely is decribed by Vernon (1998). This case study looks at an initiative in cancer nursing education in the UK, in which knowledge has been organised in such a way as to enable others to share and acquire it. This is the development of a package in CD-ROM format with the prototype running as a help-file database allowing users to navigate its content via hypertext links. The multimedia nature of the product allows users to learn, for example, by seeing procedures demonstrated, or having a dynamic illustration as an explanation of the way in which certain drugs work. This demonstrates the potential of combining individual expert knowledge with technology to allow widespread flexible access and encourage further learning according to need.

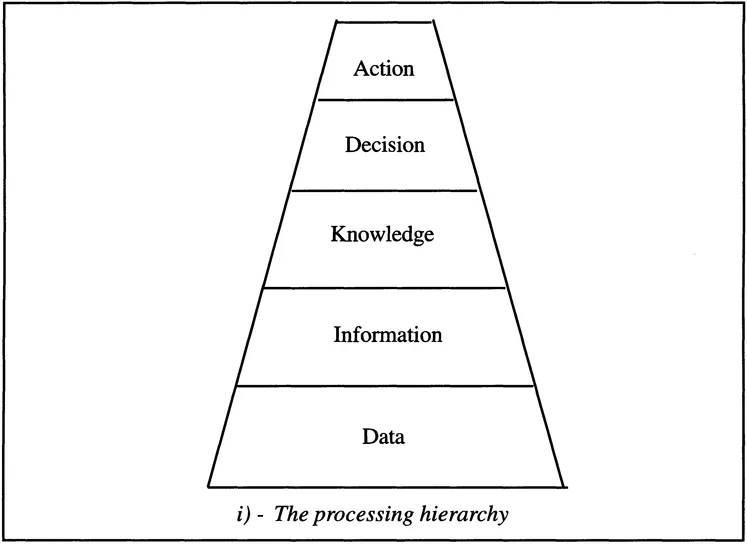

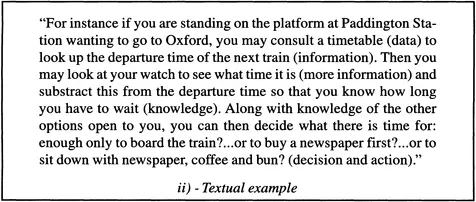

Information and knowledge can be seen as closely related and complementary stages along the same road, and as such both perform essential roles in the decision-making process. Wilson (1996) presents a useful illustration of this with the notion of the processing hierarchy. This shows that by selecting and analysing data, information can be produced; by selecting and combining information, knowledge can be generated; from this decisions can be made and action taken. Wilson has produced a simple yet extremely helpful diagram setting out the inter-relationships of the different concepts, with a short textual example which puts it into an everyday context.

Both the above are reproduced from Wilson, D.A. Managing knowledge. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann in conjunction with the Institute of Management, 1996, by kind permission of the author and publisher.

Disagreement over the meaning of the word "knowledge" is certainly not new, as Nonaka & Takeuchi (1995) demonstrate in their helpful introduction to the theory of the subject with its philosophical roots in earlier civilisations. However the notion of its formal management as an asset is more recent.

My own interest in what is currently referred to as knowledge management started some years ago. It came about in part through consideration of the way in which human beings think and operate in the work situation and arose out of earlier study in social psychology, and later through noting and monitoring the appearance and use of the term "know-how" in the business press. Although as already indicated, the concept of knowledge itself had been discussed and written about over a very long period of time, the issue of knowledge management had at that time, in the 1980s, not been widely documented in terms of its role in business strategy and management applications and the related impact on information provision and use within organisations. There were notable exceptions such as the early work of Sveiby and Lloyd (1987), and Noneka (1989), which drew attention to the formerly neglected corporate asset, namely its intellectual wealth. Although it is often suggested that what is today referred to as knowledge management was actually taking place in one form or another, there was a lack of openness about such activities, perhaps seen as giving away competitive advantage. Also, there seems to have been no widespread awareness of its potential. This therefore represented an exciting development with considerable implications for the future direction and success of a range of organisations and one which today is receiving far greater attention-you have only to look at the business press or visit any business bookshop. As for Websites, just enter the term "knowledge management" and you will be overwhelmed by the number of sites which claim to cover the subject. At the time of writing I have done just that and got the response that there are currently 137038 of these. By the time you read this there will probably be many more. (Of course you could refine the search term, or save time by noting any evaluations or descriptions of sites which are have been tried and tested, as regularly featured in the journal Knowledge Management; (see also Appendix).

Knowledge and individual expertise, as well as information, are now seen as vital to the success of a business. This is clearly demonstrated in the case studies which have been prepared for this publication. Strong evidence of the benefits of formally harnessing such assets is also set out in the report of a study of the development and impact of know-how databases (in effect knowledge management functions) in legal firms, Webb (1996).

Knowledge management is not only a key function of the commercial world; it is also relevant and applicable to many other types of organisation, as is reflected in the range of services described in the brochures of management consultancy firms and in the sessions presented at numerous knowledge management conferences. There are also now specialist journals devoted to the topic. The articles in these suggest varying views on what knowledge management is, ranging from "a new management fad?" to "something we have been doing for years but without giving it a name". This latter point also suggests that it has not been systematically pursued as a formal management activity, and that without such an approach its potential may not have been fully realised.

There seems to be agreement across various types of organisation that knowledge management contains a combination of some or all of the following features:

- recognising and building on in-house individual expertise

- formalising to varying degrees the harnessing of knowledge through the use of appropriate systems

- passing on knowledge

- developing it from an individual asset into a corporate one

- encouraging the growth of an open corporate culture in which knowledge is viewed as being central to organisational development and to the efficiency of methods of business operation.

Technology is seen to play a central role in the process, providing a sophisticated facility by which to store, organise and index details of wide-ranging expertise for future retrieval and ultimate contribution to the corporate good.

As with all good management practices, the climate in which knowledge management is able to operate effectively will need to be created through clear statements from top management and the use of appropriate communication mechanisms to ensure widespread understanding of, and commitment to both its aims and its operation. This will require careful planning of relevant staff development and training programmes, as well as the use of appropriate systems and procedures, and continuous monitoring of these to ensure that they remain effective. As Broadbent (1998) points out "Managing knowledge goes much further than capturing data and manipulating it to obtain information." The attributes of all those involved in the process provide the key to its success. Hamel (1995) notes that "A company's value derives not from things, but from knowledge, know-how, intellectual assets, competencies-all embodied in people." Rosenzweig (1998) in discussing strategies for global business, says that "A diverse workforce includes people with different world views and experiences. Making the most of diversity means forging a work environment that facilitates the sharing of ideas and the exchange of insights, inspiring novel solutions to problems." So there is increasing realisation of the importance of top management being aware of the potential of the individual as a key contributor to company strategy through knowledge management.

As this short introduction will have indicated already, there are a number of factors which an organisation will have to consider and act upon if it is to make the most of the knowledge and expertise which is present within it or is otherwise accessible. This guide sets out the key considerations and provides some practical guidelines to assist in developing and operating an effective knowledge management function. The way in which organisations operating in different sectors have gone about putting knowledge management into practice, is described in the three case studies in Chapter 9.

![]()

2. Key Management Considerations and Influences

Knowledge management, as with any organisational development or activity, is likely to be considered from the viewpoint of what it can contribute to organisational success, given the corporate aims and objectives. These in turn may suggest different ways of operating, but all organisations can benefit from having access to and making use of knowledge and information. The better it is managed, the more they are likely to benefit from it.

As pointed out by Quelin (1998), Associate Professor at the HEC School of Management in Paris, the acquisition of new knowledge and competencies is becoming more important as global competition accelerates. He also suggests that intercompany co-operation may be the way forward. Whilst this could be an anathema to some who might see it as threatening their own competitive advantage, Quelin notes that long experience of co-operating in research and development (R & D) across companies has presented opportunities for learning and the transfer of knowledge. However he also notes the possible hurdles to be overcome and the need to create an appropriate climate in which such developments can take place.

The mutual benefits of cooperation, not only between different organisations but also across sectors, are described in two recent cases of the sharing of knowledge and expertise among space agencies and the medical world, Eadie (1998). The first concerns space cool-suits and their potential for use by multiple sclerosis patients-work carried out by NASA with the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America; the second refers to the European Space Agency's work with certain metals, Shape Memory Alloys, and their subsequent application in dentistry and orthopaedic work.

The increasingly global nature of business also means that subsidiaries in every country of operation will need to accumulate their own local knowledge. Govindarajan & Gupta (1998) see some of this knowledge as being relevant across several countries and bringi...