- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Practical Approaches to Bullying

About this book

Originally published in 1991, this book is about bullying and victimisation in children and young people, and ways of dealing with it. With the exception of Chapter 13 which is related to experiences of bullying within the borstal system, superseded by Youth Custody and more recently the Unified Custodial Sentence, it is about bullying in schools.

The aim of this book is to help teachers, school governors, and parents work towards reducing the effects of behaviour which can, at worst, blight the lives of victims into adulthood and encourage antisocial and violent behaviour in those who get away with bullying.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Practical Approaches to Bullying by Peter K. Smith,David Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Behavioural Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Dealing with Bully/Victim Problems in the U.K.

Peter K. Smith and David Thompson

What is bullying?

Bullying, and related terms such as harassment, can be taken to be a subset of aggressive behaviour. As with aggressive behaviour generally, bullying intentionally causes hurt to the recipient. This hurt can be both physical or psychological; while some bullying takes the form of hitting, pushing, taking money, it can also involve telling nasty stories, or social exclusion. It can be carried out by one child, or a group.

Three further criteria particularly distinguish bullying. The hurt done is unprovoked, at least by any action that would normally be considered a provocation. (Being clumsy, for instance, might invoke some bullying but would not normally be considered a legitimate provocation). Bullying is thought of as a repeated action; something that just happens once or twice would not be called bullying. Finally, the child doing the bullying is generally thought of as being stronger, or perceived as stronger; at least, the victim is not (or does not feel him/herself to be) in a position to retaliate very effectively. These latter characteristics mean that bullying behaviour can be extremely distressing to the recipient, and the long-term effects particularly unfortunate.

Teasing provides a category of behaviour that overlaps with bullying, being persistently irritating but in a minor way or such that, dependent on context, it may or may not be taken as playful (Pawluk, 1989). In our own work we have included ‘nasty teasing’ as bullying (see Chapter 10).

Ways of assessing bully/victim problems

There have been several ways of assessing bully/victim problems. Ahmad and Smith (1990) compared a number of different methods on a sample of about 100 children aged 9, 11, 13 and 15 years. One measure used was the ‘Life in Schools’ booklet of Arora and Thompson (1987). This asks children to report whether a number of kinds of behaviour have happened to them over the last week, as well as asking explicitly about bullying. Children are asked to put their name on the booklet. Another measure was a questionnaire used in Norway by Olweus (1989), modified in slight ways. There is a version for middle school and a slightly more extended version for secondary school, with some 20-25 questions each with multiple-choice answer format. The questionnaire is anonymous and this is stressed when it is administered, usually on a class basis (see Chapter 10).

Thirdly, individual interviews were conducted; these consisted of going through the ‘Life in Schools’ booklet and the Olweus questionnaire individually with the student, and in addition asking further questions about what bullying is, and if they bullied or were bullied, what happened, and how long did it last. Finally, each class teacher was asked to nominate any bullies or victims in their class, as were children themselves.

We concluded that interviews were not most suitable as a means of studying the incidence of bully/victim problems; they did not bring to light new cases, and with some children led to defensive answers. However in the case of students willing to talk about their experiences, they can give a rich insight. Teacher nominations of victims correlated quite well with questionnaire responses, but agreement for bullies was not so high. Peer nominations by children show better agreement and generally show high consistency.

We feel that the best method for establishing incidence from middle school age upwards is the anonymous questionnaire. This can be supplemented by peer nomination for more intensive study of particular groups. Our confidence in the anonymous questionnaire is enhanced by the general consistency children show in answering the 25 or so separate questions. Only a very small proportion of children (around 1 per cent) hand in invalid questionnaires, possibly deliberately. Most treat the exercise very seriously.

The occurrence of bully/victim problems

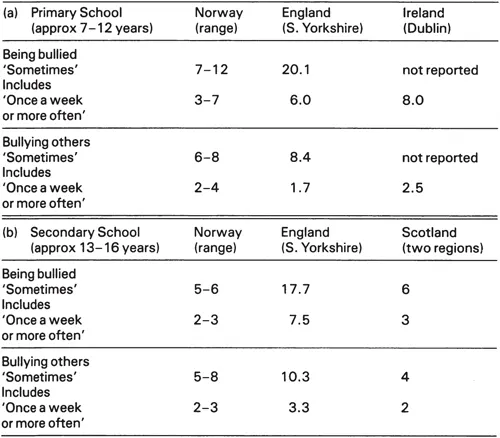

Using the modified Olweus questionnaire, Yvette Ahmad and Peter Smith estimated the incidence of bully/victim problems in about 2, 000 pupils in 7 middle schools and 4 secondary schools in the South Yorkshire area. The questionnaires were given about five to eight weeks into a school term. The results are shown in Table 1.1; figures exclude the responses ‘I haven't been bullied’, and ‘It has only happened once or twice'; and are reported separately for moderate bullying ('sometimes'/'now and then’ or more often) and severe bullying ('once a week or more often'). These figures are quite alarming, suggesting an incidence of up to 1 in 5 for being bullied, and up to 1 in 10 for bullying others.

Table 1.1 Approximate percentages of pupils who report being bullied, or bullying other pupils, in four countries. The Norwegian figures are a range based on pre- intervention figures from Roland ( 1989) and Olweus ( 1989); the English figures are based on data from Ahmad and Smith; the Irish figures (primary schools only) are from O'Moore and Hillery ( 1989), and the Scottish figures (secondary schools only) from Mellor ( 1990). All the studies used a similar questionnaire.

There have been earlier reports in England, using different methods of assessment, which have nevertheless come up with figures of the same order of magnitude. These include Lowenstein (1978), J. and E Newson (1984), Kidscape (1986a), Arora and Thompson (1987) and Stephenson and Smith (1989).

Since the questionnaire method used was almost the same as that of Olweus (1989) in his extensive surveys in Norway, we can compare our results directly with his, see Table 1.1. The incidence in middle schools is higher in England, but only for reports of being bullied moderately; the incidence is much more clearly higher in secondary schools. The problem does not seem to decline here in secondary schools in the way in which it does in Norway.

In 1989 there were some press reports that ‘Britain is “bullying capital of Europe” ‘ (The Guardian, 28/9/89) and ‘Bullying in our schools is worst in Europe - claim‘ (Sheffield Star, 28/9/89). These claims were alarmist, though they did serve to focus concern on what is certainly an unacceptable level of reported bullying. At present however we need a much wider range of data in England, and an examination of urban/rural and regional as well as school differences. There is even less data from other European countries; but some comparable data is included in Table 1.1. Mellor (1990) analysed 942 responses from 10 secondary schools in Scotland, and reported 6 per cent bullied ‘sometimes or more often’ and 4 per cent bullying ‘sometimes or more often'; as lowor lower than the Norwegian figures. He states that ‘the findings do call into question recent press reports that “Britain is the bullying capital of Europe” ‘. However a report on 783 children from 4 Dublin primary schools by O'Moore and Hillery (1989), found that 8.0 per cent were seriously bullied (once a week or more often) and 2.5 per cent bullied others this frequently. They conclude that ‘these figures indicate an incidence that is about double that in Norway’.

Olweus (1989) surveyed 60 schools in Sweden, and reported that ‘bully/victim problems were somewhat greater and more serious in the Swedish schools than the Norwegian schools’. Garcia and Perez (1989) used a questionnaire with 8-12 year olds at 10 schools in Spain. They reported ‘17.2 per cent bullied this term... it is obvious that bullying does take place with nearly a fifth of the school population’. These various findings suggest that Norway (and also Scotland) may have relatively low figures. The figures from Spain and Ireland seem very comparable to those obtained in England.

The nature of bullying

The questionnaire data from these studies also tell us about the nature of bully/victim problems. Most of the children or young people who report being bullied say that it takes the form of teasing; but about a third report other forms such as hitting or kicking, or (more occasionally) extortion of money. These latter may seem the more serious forms, but some ‘teasing’, especially that related to some disability, or which takes the form of racial or sexual harassment, can be very hurtful.

Racial harassment can be a severe problem in some multi-ethnic schools (Kelly and Cohn, 1988; Burnage Report, 1989). In a study of junior schools in London, Tizard et al., (1988) found that about a third of pupils reported being teased because of their colour; black children more than white children. In a survey by Malik (1990) of 612 secondary school children, again a third reported they had been bullied, and over a third of these reported being bullied by someone from another racial background. A significantly higher proportion of Asian children reported being bullied in this way. Kelly and Cohn (1988) surveyed three secondary schools and found that two-thirds of students reported they had been teased or bullied, and that much of this was name-calling; again Asian children suffered this the most though it was high in all racial groups. The situation in multi-ethnic settings is, however, clearly complex, and variable between particular situations.

There are fairly consistent gender differences. Boys report, and are reported as, bullying more than girls; whereas boys and girls report being bullied, about equally. However there may have been some under-reporting of girls’ bullying, as it more usually takes the form of behaviours such as social exclusion, or spreading nasty rumours, rather than the physical behaviours used more by boys. The more physical behaviours are perhaps more obviously seen as bullying, although the psychological forms are also included in our definition (see Chapter 10).

Most of the bullying reported is by children or young people in the same class or at least the same year as the victim. Some is by older pupils, but not surprisingly, little is by younger pupils. Victims are more likely to report being alone at break time, and to feel less well liked at school; having some good friends can be a strong protective factor against being bullied. However this potential support needs to be harnessed; most pupils did not think that peers would be very likely to help stop a child being bullied.

By contrast, many pupils thought that a teacher would try to stop bullying. However despite this general perception, only a minority of victims report that they have talked to a teacher or anyone at home about it, or that a teacher or parent has talked to them about it. Teachers are often not aware of bullying in the playground, since supervision at break time is now undertaken by lunchtime supervisory assistants (who usually receive little if any training for the job). Not all approaches to teachers are sympathetically received, and unless the school has a very definite and effective policy, the bullied child may well feel afraid of retribution for ‘telling’. Victims are also often unwilling to involve their parents, partly because they may blame themselves, partly because of embarrassment and possible unforeseen consequences if the parents go to complain to the school.

Possible subgroups of children who are bullied or victimised

Although it is tempting to talk of ‘bullies’ and ‘victims’, it is possible and indeed likely that this is an over-simple typology. Using data based mainly on teacher reports, Stephenson and Smith (1989) suggested five main types of children are involved. ‘Bullies’ are strong, assertive, easily provoked, enjoy aggression, and have average popularity and security. ‘Anxious bullies’ by contrast have poor school attainment, and are insecure and less popular. ‘Victims’ tend to be weaker, lack self-confidence, and are less popular with peers. ‘Provocative victims’ by contrast are active, stronger, easily provoked, and often complain about being picked on. Finally, ‘bully/victims’ are also stronger and assertive, and are amongst the least popular children, both bullying others and complaining about being victimised.

Olweus (1978) distinguished between ‘passive’ victims (anxious, insecure, failed to defend themselves) and ‘provocative’ victims (hot- tempered, created tension, fought back), and Perry, Kusel and Perry (1988) made a similar distinction between low-aggressive and high- aggressive victims. These provisional typologies need further investigation. It is also worth bearing in mind that some people object to the terms ‘bully’ and ‘victim’ as having dangerous possibilities in labelling children in undesirable ways. At least so far as discussing specific children is concerned, it may be better to talk only of ‘bullying behaviour’ rather than of ‘bullies’ per se.

Consequences of being bullied, or bullying others

How much does bullying really matter? One can still encounter the view that bullying is a training for ‘real life’ and a necessary part of growing up. Yet the more serious forms of bullying, at least, can have very serious consequences; ‘real life’ would no doubt seem a welcome escape for those being victimised. For children being bullied, their lives are being made miserable often for some considerable period of time. Already probably lacking close friends at school, they are likely to lose confidence and self-esteem even further. The peer rejection which victims often experience is a strong predictor of later adult disturbance (Parker and Asher, 1987). Research by Gilmartin (1987), using retrospective data, found that some 80 per cent of ‘love-shy’ men (who despite being heterosexual found it very difficult to have relationships with the opposite sex) had experienced bullying or harassment at school.

We are not yet certain whether bullying in itself may cause such later relationship problems; but some insight can be obtained from in-depth life history interviews. The following extract, obtained from a woman aged 28 who experienced being bullied through much of her school career, and was just engaged to be married, illustrates how intense bullying in the middle school period seems to have left a long-term anxiety about children which, while not precluding a heterosexual relationship, is having an impact:

Do you feel that's left a residue with you... what do you feel the effects are?

... I'm quite insecure, even now... I won't believe that people like me ... and also I'm frightened of children... and this is a problem. He [fiance] would like a family, I would not and I don't want a family because I'm frightened of children and suppose they don't like me? ... those are things that have stayed with me. It's a very unreasonable fear but it is there and it's very real.

The most severe consequences of bullying, thankfully rare but not unknown, can be the actual suicide of the victim, or their death as a direct or indirect result of bullying, as in the Burnage High School case (Burnage Report, 1989).

There are also consequences for those who bully others, with impunity. They are learning that power-assertive and sometimes violent behaviour can be used to get their own way. Unless counteracted, such forms of behaviour can have considerable continuity over time (Olweus, 1979; Lane, 1989), and lead to further undesirable outcomes. A follow-up by Olweus (1989) in Norway, of secondary school pupils to age 24, found that former school bullies were nearly four times more likely than non-bullies to have had three or more court convictions. In the UK, Lane (1989) reports that involvement in bullying at school is a strong predictor of delinquency...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- CHAPTER 1 Dealing with bully/victim problems in the UK

- Classroom based approaches in schools

- Using story and drama

- LEA initiatives

- Bullying in residential settings

- Conclusions

- References

- Index