![]()

1 Introduction

Kenneth Button, Gianmaria Martini,Davide Scotti

It is rather ironic that while modern economists generally trace the origins of the current core of their subject to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, they are not very good at explaining why some nations are wealthier than others, or why some are growing faster. Abstract models abound that point, in various degrees, to the roles of natural resources, stable political regimes, access to markets, cultural traits, and so on, but experience suggests that none is better at forecasting the next big economic superpower, or the timing of a major recession than simply tossing a die.

But going back to Adam Smith, his main explanation revolves around the economic progress that accompanies the division of labour and the economies that accrue from specialization. He uses his famed labour specialization in pin production as empirical evidence of this. But with this comes the need for trade, the people who spend their time sharpening the pins need to be able to trade with those who card them or add the cap. Trade is, in this sense, at the core of wealth creation; without it there can be no specialization or division of labour. And here we are not talking about international trade, which in the day of short-hand journalism is often seen as the only form of trade, but the more generic, everyday trade that takes place between individuals, firms, and government, and every combination thereof, at the micro level.

Most trade in physical goods involves some form of transportation, and this includes, in the modern world, electronic transportation of money and information. What emerges from this, when approached from this generalized framework is that, in general, the parts of the world with the greatest wealth are also those with the most efficient transportation systems. Of course, one can debate issues of causality – does transportation lead to wealth creation, or does the acquisition of wealth facilitate investment in transportation? But at the mega, geographical level there is clearly correlation, and at the very least, appropriate transportation does seem to act as a facilitator, if not always the driver, of economic growth and wealth creation.

Remaining at the mega level, the part of the world that has the least wealth per capita is Africa; e.g. while according to the United Nations, in 2000 (the last year data is available) North America held 27.1 percent of the world’s net wealth in purchasing parity terms but only had 5.7 percent of the population, and Europe 26.4 percent of the wealth with 9.6 percent of the population, Africa share of the wealth was only 1.52 percent with 10.7 percent of the global population. If one looks at the dynamic situation, rather than Smith’s focus on stocks of wealth, then there is little evidence of convergence. The wealthier parts of the world have the largest increases in absolute money GDP, although for periods, in percentage terms, their increases may be slower.

Of course, there may be many reasons for this distribution, but, by looking at the very basic statistics, the pattern corresponds with the quality of transportation in the various continents. Africa has, for example, by all the measures used by the World Bank, the worse road, railroad, and airport infrastructure, both in terms of quantity and quality of any Continent (Gwilliam, 2011). It also has the least number of cars, trucks, and commercial aircraft.

While there are important differences in the roles of the various forms of transportation in facilitating the trade that fosters the growth of wealth, the focus here is on the aviation sector. Of course, given the network nature of transportation, together with the multimodal nature of most trips or goods movements – you cannot ship flowers by air without adequate surface transportation to and from the airports involved – this does involve drawing a rater artificial boundary, but it is a practical one and institutionally aviation does tend to be treated separately, even if this is often inappropriate from an economic perspective.

The papers in this volume, all of which are original contributions, and that are outlined at the end of the Introduction, cover some of the main themes that have become important in ongoing debates about the African air transportation market, and the political economy of its development. Before moving on to explain the justification for the structure of the book, in the following pages the papers are essentially set within the larger context of African aviation. To this end we begin with a look at the larger picture of African air transportation in the early part of the 21st century, and to highlight some of the ongoing trends that would seem of an enduring nature.

African aviation

Over the past 15 years or so, Africa in general, and especially sub-Saharan Africa, has, albeit unevenly, been enjoying something of an economic boom. The demand for its raw materials has been one factor in this, as has the relative political stability of many of its constituent countries. Outside aid and investment strategies may also have removed some of the burden of limited local resources. This economic situation both provides resources for upgrading the continent’s infrastructure while at the same time placing increasing demands on it. In this context, there has been considerable interest by non-African countries, in addition to former colonial powers, both for political-military and commercial reasons, in investing in African infrastructure and production. For example, China has shown considerable interest, as have other non-ex-colonial countries, such as Iran and North Korea, but actual financing has been rather limited, and often difficult to disentangle from investment in non-aviation activities (Infrastructure Consortium for Africa, 2014).

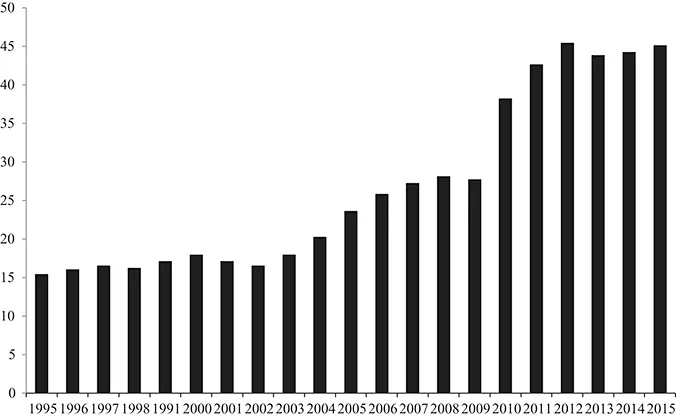

Despite its landmass of 11,730,000 square-miles, a population of 1.02 billion and population density of 87 persons per square-mile, Africa makes the lowest use of air transportation of any of the major continents. African air transportation represents somewhat less than two percent of world passengers, and less than 1.5 percent of the cargo market by tonnage. Put another way, Africans only fly 0.3 trips a year, compared to 1.7 in the “developed world” and over five times that in the US. These data should, however, be put in the context of recent growth trends in air traffic that have, in the case of sub-Saharan Africa (depicted in Figure 1.1), been faster than most other mega-regions. The political difficulties in Northern Africa, basically the Maghreb countries, have more recently been disrupted by political factors that have seen breakdowns in many of their internal and external markets, and other institutions.

Averaging across this, overall the forecasts for aviation activities are somewhat optimistic. Boeing Commercial Aeroplane (2015), for example, predicts that intra-Africa revenue passenger miles flown will grow an average of 6.7 percent a year between 2015 and 2034, and those between Africa and the Middle East and Asia by 7.3 and 7.1 percent, respectively. Physically, air cargo is projected to grow by 6.6 percent a year compared to global growth rate of 5 percent. The UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization indicates steady growth with passenger traffic to, from, and within Africa increasing at an annual average rate of 5.3 percent until 2030, while cargo traffic is projected to grow at 5.6 percent. Africa-Middle East traffic is forecast to expand at 9.9 per cent, the most rapid in the world. The forecasts produced by Airbus offer a similar picture. Where the forecasts differ is more at the micro level than in terms of the overall pictures being painted.

This economic dynamism in many of the continent’s markets, and the expectation of the continuation of stable political conditions, largely explains the longer terms scenarios of Boeing, Airbus, and others regarding the future. They, when combined with the need to replace the region’s aging fleet, are predicting a demand for between 1, 117 (Airbus) and 1, 150 (Boeing) new airplanes, with majority of them being single-aisle over the next 20 years. This in turn raises questions of how these purchases are to be financed.

The historically low level of economic development and income across most of the African Continent obviously provides a major explanation for the relatively small size of its commercial aviation sector, but geography and political history are also important (Pirie, 2014). Many of the African countries are artificial creations stemming from colonial days with limited internal political or economic cohesion. Large areas of virtually uninhabited, and probably uninhabitable, land could with natural barriers have made surface transportation difficult and costly, and especially so in the case of the land-locked nations (Limdo and Venables, 1999).

A major change in Africa’s lot is that incomes on average have been rising, albeit with local geographical variations. Added to this, recent adjustments to National Income Accounts indicate that the base levels are higher than thought only a year or so ago. Nevertheless, whatever methodology is used, most of the populations of African countries come within the lower spectrum of material welfare.1

Furthermore, the gains have yet to produce a large middle, professional class in most of Africa, and it is this group that elsewhere tend to fly the most. Taking other things as being equal, there is a high positive correlation between countries’ per capita income and their use of air transportation although this relationship is not linear. In general, it follows a sigmoid path over time. Incomes outpace air travel initially, there is then a more rapid growth in air travel, which, as in the case of North America and Europe, tends to fatten out at higher levels of income. At lower levels of income, those relevant for most African states, growth is relatively slow for a variety of reasons, such as a lack of adequate infrastructure and, not uncommonly, misguided aviation policies. But even allowing for this, the distributions of income are important; at lower levels these tend to be bimodal involving a relatively small middle class, ultimately the main users of air transportation.

In virtually all countries in Africa the main users are from higher income groups and this, because of their relatively low demand elasticities, incentivizes airlines to charge high fares and not to operate at maximum efficiency, a fact compounded by the lack of effective completion in many local markets (Button et al., 2017). Airline costs in Africa are also generally above the global average, partly caused by fuel taxes that can be 50 percent or even 100 percent higher than the global average, but also due to the higher levels of state involvement in supplying infrastructure and restrictive regulatory environments.

In terms of its “network geography”, African has little of the advantages of either the US/Canada market or that of Europe, or indeed that of China. Africa is an awkward “shape” for airline networks. The US is ideal for hub-and-spoke systems with its 48 contiguous states forming a virtual square embracing large populations at each corner. These entry points can be considered gateways for international traffic as well as large markets for domestic traffic, and major cities in the centre to act as hubs. Equally, Europe is almost ideal for discrete, short-haul, non-connecting services emanating from bases, Ryanair’s model, with the bulk of its population and economic activity in a dense corridor stretching from North West England across London to the Benelux states and along the German Rhineland, Southern Germany, and Switzerland to Northern Italy; the “Blue Banana”. China, with its concentration of economic activity in the south and west, is, in many ways, like the internal European market. The linear networks found in places such as Norway that facilitate “bus-stop routes”, with planes maintaining their load factors by picking up and dropping passengers as they move along routes, are also not viable in sub-Saharan Africa, although possibly technically so in parts of the Maghreb. Notwithstanding the current political situation, the Maghreb is more akin to Europe and in terms of its air networks, although much less dense, and with a lower income.

Added to this, there are not the levels of economic ties between the African states that are a feature of the countries of the Europe Union or the states in the United States. Historically there has been more trade between the Maghreb countries than between those within sub-Saharan Africa, and especially the land-locked countries, but it is still limited (Button et al., 2016). Complementarity between markets is a key component for fostering trade and, ipso facto, aviation, and this is limited within the Continent. Indeed, much of Africa’s trade is with countries external to the continent.

The history of Africa, and especially that of 19-th and 20-th century colonialism, has done little to foster wider economic integration in sub-Saharan Africa. In consequence, the degree of integration of airline markets and their infrastructure leaves much to be desired (Button et al., 2015b). This seems so regarding external commercial aviation markets. Overall, while African registered airlines now provide about 92 percent of the intra-sub-Saharan African annual seats on offer, only about 35 percent of the 11 million African/European seats are provided by African airlines, and 37 percent of the six million African/Middle East seats.

But within these aggregates are a series of sub-markets. For example, much of the external capacity serving Africa has traditionally been provided by the flag airlines of the former colonial powers associated with individual states, making any widening of external markets difficult, especially when overall aviation is growing slowly. Equally, the high proportion of intra-continental capacity offered by African airlines disguises very significant levels of spatial market segmentation.

Institutional problems caused by a lack of market liberalization are widely understood by governments across Africa, as well as international agencies like the International Civil Aviation Organization. Until the 1990s, intra-African air transport services were regulated by highly restrictive, bilateral agreements, with nearly all carriers state-owned and lacking the commercial focus for profitability. The African airlines were characterized by mismanagement of national carriers, political interference, high operating costs, and outdated equipment. The focus of carriers has also remained on international traffic, with the intra-African network taking a secondary role.

In 1999, as a follow-up to the 1988 Yamoussoukro Declaration, 44 countries adopted the Yamoussoukro Decision seeking to address this, although national ratification has been slow. The Decision was a commitment to deregulate air services and to open regional air markets to transnational competition. Using simulations, InterVISTAS (2014) suggests that if the Decision were fully implemented, increased air services between 12 sample markets across the continent could provide an additional five million passengers per annum, $1.3 billion in annual GDP, and 155,000 jobs.

The expected gains have, however, yet to materialize (Schlumberger, 2010). In practice while there has been a degree of operational integration that, for example, contributed to the 69 percent increase in traffic between South Africa and Kenya in the early 2000s and to the 38 percent reduction in fares between South Africa and Kenya, public policies have not been integrated to the extent envisaged. Overall, however, comparing those regions where Yamoussoukro has been implemented, frequencies have grown faster; new, privately funded airlines have emerged; and services improved more than where that was not the case (Njoya, 2016).

Infrastructure

Africa’s transportation infrastructure, and particularly that of the sub-Saharan region, is poor, and this certainly extends to aviation (World Bank, 2009). In 2013, the Secretary General of the African Airlines Association summed it up thus, “deficient, dilapidated and not coping with the growing airline industry”. The pressure for improving the quality and quantity of air transportation infrastructure is not just being driven by macroeconomic growth in Africa – seven of the world’s ten fastest-growing economies in percentage terms are African and in sub-Saharan Africa – but also by the emergence of “airport megacities” such as Accra, Lagos, Luanda, Addis Ababa, Nairobi, and Johannesburg, with demands over 10,000 daily long-haul passenger trips. Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi, for example, opened in 1958 with capacity of 1.5 million passengers a year. But the annual passenger flow has reached 6.5 million and it is forecast to reach 25 million by 2025.

When discussing commercial aviation infrastructure, it is normal to divide it into airports, and air navigation and control systems – often referred to as air traffic control (ATC), although this is only part of their function. Infrastructure, as in all sectors, is relative to those interested, and in this case all three elements are included; aircraft are uses as far as airports are concerned but infrastructure in the view of airlines. Because airports and ATC clearly fall under mo...