eBook - ePub

Human Factors Methods and Accident Analysis

Practical Guidance and Case Study Applications

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Factors Methods and Accident Analysis

Practical Guidance and Case Study Applications

About this book

This book provides an overview of, and practical guidance on, the range of human factors (HF) methods that can be used for the purposes of accident analysis and investigation in complex sociotechnical systems. Human Factors Methods and Accident Analysis begins with an overview of different accident causation models and an introduction to the concepts of accident analysis and investigation. It then presents a discussion focussing on the importance of, and difficulties associated with, collecting appropriate data for accident analysis purposes. Following this, a range of HF-based accident analysis methods are described, as well as step-by-step guidance on how to apply them. To demonstrate how the different methods are applied, and what the outputs are, the book presents a series of case study applications across a range of safety critical domains. It concludes with a chapter focussing on the data challenges faced when collecting, coding and analysing accident data, along with future directions in the area. Human Factors Methods and Accident Analysis is the first book to offer a practical guide for investigators, practitioners and researchers wishing to apply accident analysis methods. It is also unique in presenting a series of novel applications of accident analysis methods, including HF methods not previously used for these purposes (e.g. EAST, critical path analysis), as well as applications of methods in new domains.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Accidents, Accident Causation Models and Accident Analysis Methods

1.1 INTRODUCTION

A topic of interest for many years (e.g. Heinrich 1931), various perspectives on accident causation are presented in the academic literature. Whilst not wishing to enter into debate over which are the most appropriate accident causation models to emerge from the discipline of Human Factors, it is worthwhile to orient the reader by providing a summary of some of the more prominent perspectives available. First and foremost, however, clarification is required over what we mean by the term ‘accident’. Hollnagel (2004) presents a neat account of the etymology surrounding the term accident, and goes on to define an accident as follows: ‘a short, sudden, and unexpected event or occurrence that results in an unwanted and undesirable outcome’ (Hollnagel 2004, 5).

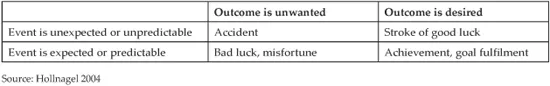

Hollnagel (2004) further points out the event must be short rather than slowly developing and must be sudden in that it occurs without prior warning. Usefully, to minimise confusion further, Hollnagel also goes on to distinguish between accidents, bad luck, misfortune, good luck, and achievement or goal fulfilment. This distinction is presented in Table 1-1, which shows that although there are two situations in which the outcome is unwanted (i.e. an accident or bad luck/misfortune), only those in which the event is unexpected or unpredictable should be labelled accidents.

Table 1-1 Events and outcomes

1.2 MODELS OF ACCIDENT CAUSATION

Various models of accident causation exist (e.g. Heinrich 1931; Leveson 2004; Perrow 1999; Rasmussen 1997; Reason 1990) each of which engender their own approach to accident analysis. Generally speaking, the view on accident causation has evolved somewhat over the past century, with an early focus on hardware or equipment failures being superseded by increased scrutiny on the unsafe acts or ‘human errors’ made by operators, following which failures in the wider organisational system became the prominent focus during the late 1980s and early 1990s. It is now widely accepted that the accidents which occur in complex sociotechnical systems are caused by a range of interacting human and systemic factors (e.g. Reason 1990).

Although some disagree with the classification (e.g. Reason 2008), Hollnagel (2004) distinguishes between three types of accident causation model: sequential, epidemiological, and systemic accident models. Sequential models, characterised by Heinrich’s (1931) domino theory accident causation model, view accidents simply as the result of a sequence of linear events, with the last event being the accident itself. Epidemiological models, characterised by Reason’s ‘Swiss cheese’ model (although Reason himself disagrees with this, Reason 2008), view accidents much like the spreading of disease (Hollnagel 2004), and describe the combination of latent conditions present in the system for some time and their role in unsafe acts made by operators at the so-called ‘sharp end’ (Reason 1997; Hollnagel 2004). Finally, systemic models, as characterised by Leveson’s Systems Theoretic Accident Modelling and Processes (STAMP; Leveson 2004) model, focus on the performance of the system as a whole, as opposed to linear cause effect relationships or epidemiological factors within the system (Hollnagel 2004). Under this approach, accidents are treated as an emergent property of the overall sociotechnical system.

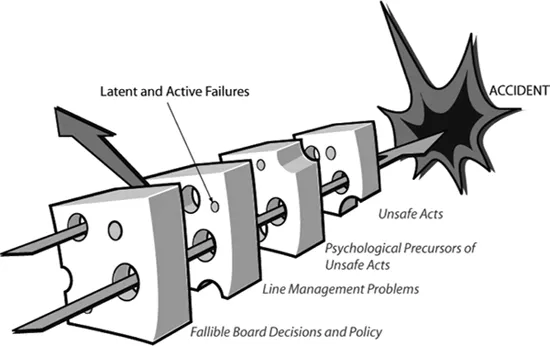

In the following section we will briefly outline some of the more prominent accident causation models. Regardless of classification, undoubtedly the most popular and widely applied model is Reason’s (1990) Swiss cheese model (Figure 1-1). Its popularity is such that it has driven development of various accident analysis methods, e.g. the HFACS aviation accident analysis method (Wiegmann and Shappell 2003) and has also been commonly applied itself as an accident analysis framework (e.g. Lawton and Ward 2005). Reason’s model describes the interaction between system-wide ‘latent conditions’ (e.g. poor designs and inadequate equipment, inadequate supervision, manufacturing defects, maintenance failures, inadequate training, poor procedures) and unsafe acts made by human operators and their contribution to accidents. Importantly, rather than focus on the front line or so called ‘sharp end’ of system operation, Reason’s model describes how these latent conditions reside across all levels of the organisational system (e.g. higher supervisory and managerial levels). According to the model, each organisational level has defences, such as protective equipment, rules and regulations, training, checklists and engineered safety features, which are designed to prevent the occurrence of occupational accidents. Weaknesses in these defences, created by latent conditions and unsafe acts, create ‘windows of opportunity’ for accident trajectories to breach the defences and cause an accident.

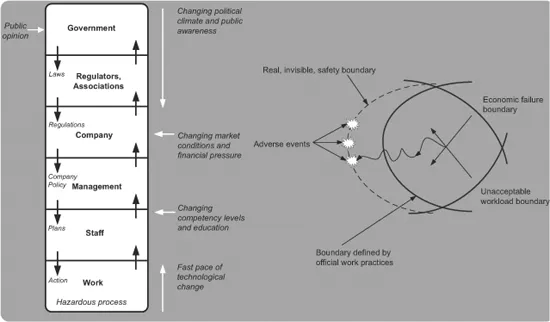

Although not enjoying the high levels of exposure and popularity of Reason’s model, other accident causation models are also prominent. Rasmussen’s risk management framework (Rasmussen 1997, see Figure 1-2), e.g. is also popular, and has also driven the development of accident analysis methods (e.g. AcciMap; Rasmussen 1997). Rasmussen’s framework is based on the notion that accidents are shaped by the activities of people

Figure 1-1 Reproduction of Reason’s Swiss cheese accident causation model (adapted from Reason 1990)

Figure 1-2 Rasmussen’s risk management framework along with migration of work practices models (adapted from Rasmussen 1997)

who can either trigger accidental flows or divert normal work flows. Similar to the Swiss cheese model, the framework describes the various organisational levels (e.g. government, regulators, company, company management, staff, and work) involved in production and safety management and, in addition to the unsafe acts made by humans working on the front line, focuses on the mechanisms generating behaviour across the wider organisational system. According to the model, complex sociotechnical systems comprise a hierarchy of actors, individuals, and organisations (Cassano-Piche et al. 2009). Safety is viewed as an emergent property arising from the interactions between actors at each of the levels.

The model describes how each of the levels comprising safety critical systems is involved in safety management via the control of hazardous processes through laws, rules, and instructions. According to the framework, for systems to function safely, decisions made at the higher governmental, regulatory, and managerial levels of the system should be promulgated down and be reflected in the decisions and actions occurring at the lower levels (i.e. staff work levels). Conversely, information at the lower levels regarding the system’s status needs to transfer up the hierarchy to inform the decisions and actions occurring at the higher levels (Cassano-Piche et al. 2009). Without this so-called ‘vertical integration’, systems can lose control of the processes that they are designed to control (Cassano-Piche et al. 2009).

According to Rasmussen (1997), accidents are typically ‘waiting for release’, the stage being set by the routine work practices of various actors working within the system. Normal variation in behaviour then serves to release accidents.

A second component of Rasmussen’s model describes how work practices evolve over time, and in doing so often cross the boundary of safe work activities. The model presented on the right hand side of Figure 1-2 shows how economic and production pressures influence work activities in a way that, over time, leads to degradation of system defences and migration of work practices. Importantly, this migration of safe work practices is envisaged to occur at all levels of the system and not just on the front line. A failure to monitor and address this degradation of safe work practices will eventually lead to a crossing of the boundary, resulting in an unsafe event or accident.

Finally, a more recently proposed accident model worthy of mention is the increasingly popular STAMP model (Leveson 2004). Underpinned by control theory and also systemic in nature, STAMP suggests that system components have safety constraints imposed on them and that accidents are a control problem in that they occur when component failures, external disturbances, and/or inappropriate interactions between systems components are not controlled, which enables safety constraints to be violated (Leveson 2009). Leveson (2009) describes various forms of control, including managerial, organisational, physical, operational and manufacturing-based controls. Similar to Rasmussen’s model described above, STAMP also emphasises how complex systems are dynamic and migrate towards accidents due to physical, social and economic pressures.

System safety and accidents are thus viewed by STAMP as a control problem. According to Leveson the following four conditions are required to enable control over complex sociotechnical systems (Leveson et al. 2003) and accidents arise when all four conditions are not achieved:

1. Goal condition. The controller must have a goal or goals, e.g. to maintain safety constraints (Leveson et al. 2003);

2. Action condition. The controller must be able to influence the system in such a way that processes continue to operate within predefined limits and/or safety constraints in the context of multiple internal and external disturbances;

3. Model condition. The controller must possess an accurate model of the system. Accidents typically arise from inaccurate models used by controllers;

4. Observability condition. The controller must be able to identify system states through feedback, which is then used to update the controller’s system model.

1.3 SUMMARY

This chapter has presented a brief overview of some of the more prominent accident causation models presented in the Human Factors literature. It is clear that, as is the case with most Human Factors concepts, the notion of accident causation has evolved somewhat since the first attempts were made to describe the causal mechanisms involved. Accidents are now most commonly viewed from a systems theoretic viewpoint, as a consequence of the inadequate, inappropriate or unwanted interactions between system components occurring at and between various levels of the complex system (e.g. Leveson 2004; Reason 1990; Rasmussen 1997). This invariably renders accidents a highly complex phenomenon and places great demand on the methods used to understand them. Also notable is that a universally accepted model of accident causation is yet to emerge. Reason’s model is undoubtedly the most popular; however, more recent systems theoretic approaches, such as STAMP, may be more appropriate given the complexity associated with modern complex sociotechnical systems. Despite this, STAMP has not yet received anywhere near the same amount of attention as Reason’s model. Although different in many ways, the most prominent models of accident causation are in agreement on at least one thing; that is, in order to exhaustively describe accidents, the entire complex sociotechnical system should be the unit of the analysis.

2

Human Factors Methods for Accident Analysis

2.1 INTRODUCTION TO HUMAN FACTORS METHODS

Many Human Factors methods exist. For the purposes of this book, these can be categorised as follows:

1. Data collection methods. The starting point in any Human Factors analysis, be it for accident analysis, system design or evaluation, involves describing existing or analogous systems via the application of data collection methods (Diaper and Stanton 2004). These methods are used to gather specific data regarding a task, device, system or scenario and are critical for accident analysis efforts, since the analysis produced is heavily dependent upon the data available regarding the accident itself. Data collection methods typically used in accident analysis efforts include interviews, observation, walkthroughs, and documentation review.

2. Task analysis methods. Task analysis methods (Annett and Stanton 2000) are used to describe tasks and systems and typically involve describing activity in terms of the goals and physical and cognitive task steps required. They focus on ‘what an operator ... is required to do, in terms of actions and/or cognitive processes to achieve a system goal’ (Kirwan and Ainsworth 1992, 1). Task analysis methods are useful for accident analysis purposes since they can be used to provide accounts of tasks and systems as they should have performed or been performed (i.e. normative task/system description) and also of how the task or system actually did perform or was performed. This is useful for identifying the unsafe acts, errors, violations, and contributing factors involved.

3. Cognitive task analysis methods. Cognitive Task Analysis (CTA) methods (Schraagen et al. 2000) focus on the cognitive aspects of task performance and are used for ‘identifying the cognitive skills, or mental demands, needed to perform a task proficiently’ (Militello and Hutton 2000, 90) and describing the knowledge, thought processes and goal structures underlying task performance (Schraagen et al. 2000). CTA methods are useful for accident analysis purposes since they can be used to gather information from those involved regarding the cognitive processes involved and the factors shaping decision-making and task performance prior to, and during, accident scenarios.

4. Human error identification/analysis methods. In the safety critical domains, a high proportion (often over 70 per cent) of accidents are attributed to ‘human error’. Human error identification methods (Kirwan 1992a, b, 1998a, b) use taxonomies of human error modes and performance shaping factors to predict any errors that might occur during a particular task. They are based on the premise that, provided one has an understanding of the task being performed and the technology being used, one can identify the errors that are likely to arise during the man-machine interaction. Human error analysis approaches are used to retrospectively classify and describe the errors, and their causal factors, that occurred during a particular accident or incident. Both approaches are useful for accident analysis purposes. Human error identification methods can be used to identify the errors that are likely to have been made given a certain set of circumstances, whereas human error analysis methods can be used to classify the errors involved in accident scenarios.

5. Situation awareness measures. Situation awareness refers to an individual’s, team’s or system’s awareness of ‘what is going on’ during task performance (Endsley, 1995). Situation awareness measures are used to measure and/or model individual, team, or system situation awareness during task performance (Salmon et al. 2009). Situation awareness modelling approaches are useful for accident analysis purposes since they can be used to mode...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Acronyms

- Preface

- 1 Accidents, Accident Causation Models and Accident Analysis Methods

- 2 Human Factors Methods for Accident Analysis

- 3 AcciMap: Lyme Bay Sea Canoeing and Stockwell Mistaken Shooting Case Studies

- 4 The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System: Australian General Aviation and Mining Case Studies

- 5 The Critical Decision Method: Retail Store Worker Injury Incident Case Study

- 6 Propositional Networks: Challenger II Tank Friendly Fire Case Study

- 7 Critical Path Analysis: Ladbroke Grove Case Study

- 8 Human Factors Methods Integration: Operation Provide Comfort Friendly Fire Case Study

- 9 Discussion

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Factors Methods and Accident Analysis by Paul M. Salmon,Neville A. Stanton,Michael Lenné,Daniel P. Jenkins,Laura Rafferty,Guy H. Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Operations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.