![]()

1 The evolution of management thought

Overview

This chapter establishes a foundation allowing for the opportunity to fully explore the differences between these two concepts. Although this book is not designed to replace a college textbook on management and leadership, this chapter presents a common foundation where readers of varied backgrounds can follow the analysis.

A brief history of management

The practice of management has been with us throughout recorded time. Egyptians in building the pyramids, Romans in performing their extraordinary engineering feats, and the myriad of other civilizations that have come and gone have all used some form of management to build and maintain their empires. However, management did not receive serious attention until the late 1800s. The attention was the result of the exponential growth of the factory system during this period, that is, the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Wren (1972) credited Phyllis Deane (1965) for pinpointing the differences between pre-industrialized and industrialized nations using such factors as per capita income, economic growth, dependence on agriculture, degree of specialization labor, and geographical integration of markets. “Using these factors as indicators, Deane concluded that the shift in England from pre-industrial to an industrial nation became most evident in 1750 and accelerated thereafter” (Wren, 1972, p. 37).

Since World War II, the study and practice of management underwent some revolutionary changes in its theoretical constructs, techniques, methods, and tools. Today with the work on complexity theory, and the crossovers from the New Sciences to the field of management espoused by Margaret Wheatley (1999), the robustness of the field of management is growing to a point where it becomes imperative that managers and leaders stay abreast of the balance between the well-grounded concepts of the past and the seemingly daily revelations of new techniques in management.

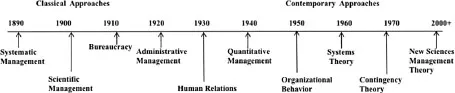

Figure 1.1 Evolution of management thought

To lay out the evolution of management in an understandable sequence, Figure 1.1 shows Bateman and Zeithaml’s (1993) timeline of some of the major categories of management thought since the early 1900s. Although management thought has evolved over time, valuable insight can still be gained from older schools of thought.

To help better understand the categories in Figure 1.1, here is a brief explanation of these categories:

- Systematic Management: The organization, supervision and oversight of the conduct of business activity based on rational processes and procedures; a formalization of a holistic view of work activity.

- Scientific Management: The management of a business, industry, or economy, according to principles of efficiency derived from experiments in methods of work and production, especially from time-and-motion studies; the effort to bring the Scientific method to the workplace.

- Bureaucracy: A rational and efficient form of an organization founded on logic, order and legitimate authority. See Chapter 2 for more details.

- Administrative Management: The theory generally calls for a formalized administrative structure, a clear division of labor, and delegation of power and authority to administrators relevant to their areas of responsibilities. This approach to management stresses the design structure in order to continue with Weber’s work on the concept of bureaucratic organization.

- Organizational Behavior: The study of individuals and their behavior within the context of the organization in a workplace setting. This branch of management started to humanize the workforce in lieu of treating workers as if they were machines.

- Systems Theory: An approach to industrial relations that likens the enterprise to an organism with interdependent parts, each with its own specific function and interrelated responsibilities.

- Contingency Theory: A theory that claims that there is no best way to organize a corporation, to lead a company, or to make decisions. Instead, the optimal course of action is contingent (dependent) upon the internal and external situation.

- New Sciences Management Theory: An integration of how new discoveries in quantum physics, chaos theory, and biology challenge our standard ways of thinking in and about organizations.

Although many people tend to disavow the classical management literature, much of our current understanding of people at work is a result of the pioneering work of classical management thinkers. Frederick Taylor, Henri Fayol, the Gilbreths, Mary Parker Follett, Henry Gantt, and Max Weber are classical management thinkers who helped move the concept of management from an agriculture society driven by lords and masters in charge of peasants to one of a more rational and scientific approach. This evolution of how society constructed itself was primarily due to the challenges of the Industrial Revolution that compelled organizations to better use and focus their resources.

Sadly many of today’s managers and leaders take these new concepts and try to apply them without a full understanding of the other factors that are usually at play in solving organizational problems. To overcome this shortfall, Chapter 2 is presented to provide the historical anchors to management concepts that are still viable today. The challenge is to take these concepts and build the bridges needed to recognize their applications in the various activities in today’s organization. The message here is to be wary of any quick fixes that do not fully account for past solutions to organizational problems. This is especially true when examining why past solutions were changed or why they should be continued. The key always has been and always will be the use of critical thinking by managers, leaders, and others at every level of the organization. Only then can they sort through the myriad of factors that affect organizational problems and weigh solutions accordingly.

What is Critical Thinking? According to Jane Willsen (1996), “Critical thinking is a systematic way to form and shape one’s thinking” (p. 419). “It is … disciplined, comprehensive, based on intellectual standards, and as a result well-reasoned” (p. 1996). In other words, this is the formal process that is used to determine the truth and validity of consumed materials in people’s lives. However, everyone does not possess the knowledge base or skill set to fully implement this process, which invariably leads to the differences we have as human beings. Some may challenge the definition above, but after operational definitions have been sorted out, most will probably agree that some phenomenon is being referenced despite the term used.

The foundation for critical thinking is the scientific method, which is defined as the process of investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, and correcting or integrating previous knowledge. To be termed ‘scientific,’ a method of inquiry must be based on empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning for analyzing observations or questions about events. Too often the problem with the application of this process seems to be the resistance in applying scientific methodology. Without going into the quagmire of why people resist the use of science and math, especially during their school years, the use of valid, reliable data in their decision-making process is crucial in critical thinking. Especially in today’s world where we are flooded by all sorts of information and too often marketing experts, salespeople or politicians use our lack of effort to seek valid, reliable evidence against us.

To add to this problem, most people do not seek knowledge outside of their specialty areas hindering their ability to independently investigate events, concepts, and facts from many perspectives before information is placed in the knowledge base and deemed valid and reliable.

The Third Wave

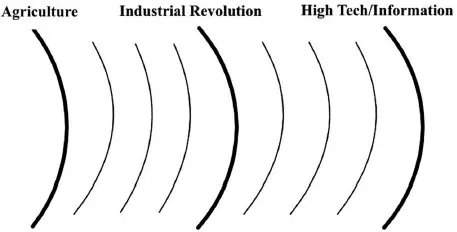

In Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave (1980), which is the second book in his trilogy on the changing face of civilization, he uses a model to set the tone for a global view of human evolution in organizational settings. In the Third Wave, Toffler points out that if you step back and look at the major movements of civilized society, there seems to be three major categories or waves of societal evolution, see Figure 1.2.

As humans moved from the Hunter-Gatherer stage of existence into a more stable life style where people cultivated the land, the change caused societal pressure on how humanity organized itself. This first wave Toffler called the Agriculture Wave. In this stage, the organizational emphasis revolved around a farming existence. As a result, the need for large pools of labor gave rise to the feudal system, slavery, and the need for large families. The management style was a dictatorial system that emphasized tight control measures. Some of the other organizational characteristics of this life style were little to no formal education for the masses and work routines based on seasonal changes. These characteristics of how man organized himself for work would later present themselves as problematic as society moved into the Second Wave, Industrialization.

Figure 1.2 Toffler’s Third Wave analogy

The Second Wave has been, and continues to be, a shock to the freedom of man in the workplace. To deal with this shock, a body of knowledge concerning factory, job design, and personnel issues had to be addressed in this evolving work environment. In a short period of time, workers’ skills were transformed from handicraft skills to machine operation skills. Additionally, to control the large volume of uneducated workers, increased levels of management were established. In addition to these increased levels of management, the use of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) was needed to focus and synchronize the workforce effort. In reality, in-depth planning processes were needed at all levels of these industrialized complexes in order to keep abreast of the exploding landscape of the Second Wave.

As an aside, many of us today are products of the socialization that evolved from the Second Wave developments. Our vocabulary, our educational process, our governmental systems, the structures of our buildings, and the way we think about civilization are all products of a Second Wave mentality. Problems that this mindset creates will become clear as the Third Wave is explored.

While this new industrialized organization afforded higher levels of efficiency and greater production, it also uncovered a critical problem, namely, mutual dependence. Since the production line was normally a piecemeal operation where workers were tied to a conveyor system, workers were now required to be at a designated station at a specific time. This work configuration was far different from the farm and craftsman routines that people were accustomed to; i.e., flexible routines where workers were, for the most part, free to set their own schedules. Now, start, break, and quit times are all regulated. Following regimented plans and SOPs became stifling to the workers. This would change with the rise of the Third Wave where maximum flexibility and less rigidity of rules and policies seem to be the new mode of operation. Notice that there was not an absence of rules and policies but rather some built-in flexibility due to the increased education, acquired experiences of the workforce, and the fluidity of the marketplace.

The last Toffler Wave is the most troubling. If moving human society from the caves to the farms to the manufacturing plant floor was not tough enough, he now foretells that humanity is challenged with an ever-increasing crescendo of new industries that would take center stage. This center stage is one where organizational complexity and chaos is the norm and the rate of change is exponential. As a result, the changes for this wave are so overwhelming that the task for organizational decision makers to find historical trends to base timely decisions on is increasingly elusive. Toffler points out that industries involving computers, electronics, information, biotechnology, and the financial industry would begin to influence the direction of the world’s economy. He continued by saying some of the features of these industries would be flexible manufacturing, niche markets, the spread of part-time work, and the demassification of the media. This Third Wave continues today, nearly twenty-four years after Toffler identified this phenomenon.

A key takeaway from Toffler’s Third Wave model is that the world is living through all three waves at the same time. Consequently, it brings into focus an understanding of the structural friction that these waves cause in organizations. In fact, it is safe to say that a key factor for the turmoil in many countries today is due to the societal friction caused by addressing all three waves at the same time, either within their own country or in other countries existing in different Toffler Waves attempting to work together.

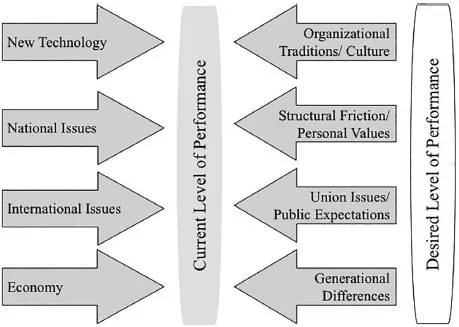

Addressing change in organizations be it in a family, educational institution, workplace or a country is a daunting task because there are obstacles to change within the organization as well as external forces pressuring the organization to evolve to a more viable existence. The use of the Kurt Lewin Change model is helpful to better grasp this idea. In Figure 1.3, an adaptation of Lewin’s model by Cummings and Huse (1989, p. 99) assists in a better understanding of the process. This figure shows just some of the factors that are pushing organizations to more desirable levels of performance while other factors present obstacles for improvement. While this diagram is an oversimplification, it represents an overall understanding of some of the forces at play.

Figure 1.3 Forces influencing change

With Toffler’s Wave model now in our analytical skills’ toolkit, the task at hand is to gain an understanding of the various management concepts that have been put forth throughout the years. These concepts by themselves are not a final solution for any organizational dilemma, but the concepts certainly can give important insights to a manager or leader trying to take their organizations through the challenges they face both today and in the future.