This book was guided by two overarching questions: first, how can IR understand IOs working at the domestic level and in particular those that appear to be surrogate states? And second, how does surrogacy affect the IO’s ability to influence the state? Many IOs working operationally “on the ground” now carry out activities far beyond their original mandates, doing everything from providing social services and security, to paying police salaries and settling land disputes. In some developing countries, populations may see an IO, not the central state, as the authority governing in their given locale.

This chapter introduces a theoretic framework on IOs at the domestic level, focusing specifically on IO surrogacy. Building on IR literature on IOs, it presents a spectrum of IO roles at the domestic level, explained by a concept called “domestication,” which describes both properties of and processes through which IOs take on different roles at the domestic level. The framework then focuses on a more extreme end of the spectrum: IOs as surrogate states. It outlines the ways in which an IO takes on surrogacy, including conditions and indicators and the ways in which states tend to react (by abdicating responsibilities to the surrogate state IO or partnering with it). The framework then considers how IO surrogacy affects its ability to influence the state in which the IO is working. It presents the counterintuitive claim that IO surrogate statehood works inversely to its influence over the state: the more an IO takes on surrogate statehood, the less capable it is to influence state behavior. Finally, the chapter seeks to understand this relationship by setting out two mechanisms: marginalization of the state and responsibility/blame shifting.

Domestication and IO surrogacy

The previous section outlined some of the shortcomings of IR’s understanding of IOs at the domestic level. While there any number of IOs working domestically, most IO literature looks at IO behavior and influence from a global level, and the IO literature that does engage with the domestic level tends to be focused on norm diffusion and institutionalization, not the domestic role of the IO itself. Thus, there is a gap in the literature addressing IOs at the domestic level—what roles they take and what these roles mean for relations with the state.

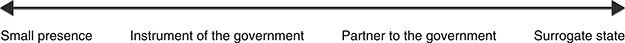

This framework responds to this gap by suggesting that IOs can “domesticate,” or take on various roles at the domestic level (e.g. instrument of the state, autonomous actor in its own right, transterritorial deployment, surrogate state), and that states react in a range of ways (e.g. abdicationist or partnership-oriented). Of these domesticated types, this book focuses on the most extreme end of the spectrum: surrogate statehood. The framework considers what it means for the IO’s relationship with the state, namely, the extent to which IOs as surrogate states can exert influence over state behavior. It does not purport that IO surrogate statehood is the only factor influencing the policy decisions states make—certainly, a number of variables influence these decisions—but nonetheless traces its role in the relationship. Thus, two interrelated questions are at play in the framework. First, how and under what conditions can IOs become surrogate states? When they do, the second question addresses what this means for the relationship between IOs operating domestically and the states in which they work.

The findings lead to a counterintuitive claim that has interesting theoretical implications. At first glance, one might initially expect an actor with a large presence, lots of funding and responsibility for a large number of people to have more political influence. This would be a natural assumption: actors that take on state-like properties (surrogate statehood) at the domestic level garner greater influence. Instead, the framework suggests that IO surrogacy has an inverse relationship to influence over state policy decisions; the closer to surrogacy an IO gets, the less influence it tends to have over the state in which it is working. This “less is more” outcome can be explained via two primary mechanisms—marginalization of the state and responsibility shifting—both of which are explored on p. 31. Thus, besides contributing to understandings of IOs working domestically, focusing specifically on surrogate statehood reveals, not only that IOs can and do work domestically as surrogate states, but that surrogate statehood does not necessarily increase influence over the state.

The sections in this chapter unpack what is meant by surrogate statehood and some of the characteristics attributed to an IO assuming surrogate state-hood. However, it is important to begin the analysis by noting that surrogate statehood is not binary but rather falls along a spectrum. Surrogacy is measured via both material things (e.g. the IO provides services that the state would normally provide; it may pay policy salaries or pave roads; it may even administer or adjudicate, such as helping to broker land deals) and nonmaterial things (e.g. the IO is perceived by local communities to be an authority; rhetoric may indicate that it is seen as having state-like power). Influence, also discussed further on p. 27, is defined as the ability to affect outcomes; to sway decisions that might otherwise take a different direction; and even to pressure, impact and hold some level of authority.

Before moving forward, however, it should be mentioned that, while the scope of the framework is generalizable to other IOs, it does not apply to IOs working in emergency situations such as war, famine or natural disasters, which in turn would exhibit an entirely different set of political variables, different actors and different roles for the state and emergency response IOs. Rather, the focus on surrogacy is by definition something that evolves with the passing of time and therefore should not be examined in emergency settings. In addition, the framework helps unpack one aspect of IOs working at the domestic level: the way in which an IO can take on surrogate state characteristics and what that means for its relationship with the host state. Thus, it is important to stress that the framework and the causal relationships are narrow in scope: they are not meant to explain all of the different variables that go into policy processes and decisions on the part of states. Finally, the framework cannot be generalized to imply that less IO involvement from an international standpoint would have the same effects (more or less influence) as less involvement from a domestic standpoint—in other words, the “domestic” IO claims offered here do not necessarily translate to “international” IO behavior.

“Domestication” of an IO: a spectrum of IO roles at the domestic level

The literature discussed earlier outlines some of the ways IOs are viewed by IR scholars, including as an instrument of states, as an autonomous actor, as a network or transnational actor, as a forum for debate and discussion, as an interlocutor, as a norms-setter, as a creator and generator of knowledge, and any number of other roles (see Ian Hurd 2011, 16).1 This study argues that IO literature lacks an understanding of how IOs act at the domestic level— not simply through the diffusion of norms or through other domestic actors, but as an actor in its own right at the domestic level. Zooming in from the global to the domestic level, then, this section sketches a spectrum of roles IOs may take at the domestic level, using the concept of “domestication.”

Domestication points to the ways in which an IO becomes embedded into a given locale in a way that is unique to its otherwise international status. It thus describes different degrees to which an IO can be involved domestically and furthermore the different labels and characteristics it might assume. Being mindful of Michael Barnett’s (2001) argument on avoiding analytical entrapment from the rigid categories of “local,” “national,” “global” and “international” (see p. 34), domestication helps uncover the processes by which an IO’s role can be altered from its international roles when it works operationally on the ground. Working within the domestic level does not mean that the IO ceases to be “international” and becomes a domestic actor entirely, but it does imply that an IO can straddle multiple identities at once. Ronald Kassimir’s (2001) depiction of the Catholic Church as a multileveled institution parallels the concept: just as the Catholic Church maintains an international presence, with the Pope in Rome, it also works domestically through local parishes, in a sense holding multiple identities at once. Numerous IOs, from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to UNHCR, can be described this way.

Domestication is therefore a descriptive concept relating to IO behavior. Operationalization or having a field presence is not the same as domestication—indeed they are part of it, but there are also deeper implications relating to responsibility, authority and status, as described on p. 23.2 In contrast to other uses of the word, it is not meant to imply that the IO is somehow “tamed” but rather points to the process by which it takes on properties at the domestic level. These properties may or may not differ from all of its international properties and could include a range of behaviors (e.g. participating in local politics, hiring local staff and conducting business according to local customs3 or governing a given locale). All require a physical presence on the ground—not through partners or networks, but of the IO itself (though this book does have some discussion of working through subcontracted organizations, which is quite common). As Figure 1.1 shows, an IO at the domestic level can take on a range of roles from working undercover in a small capacity to being a surrogate state, all while maintaining its international identity and global role.

Figure 1.1 Spectrum of “domesticated IOs” with examples

Each type of “domesticated IO” could be the subject of its own book, harboring its own nuances and complexities. IOs can move in any direction along the spectrum or remain static. Moreover, IO surrogate statehood is not the automatic outcome (and may in fact be the rarest of outcomes). Furthermore, it should be noted that all IOs do not necessarily domesticate. Indeed, many work solely through domestic partners, which is well documented in the literature and not the focus here.

Looking at the spectrum of domestication helps unpack how an IO becomes a surrogate state. Although few scholars have employed the term, Cyril Obi (2001), for example, uses “domesticated” to describe how some multinational oil companies (MNOCs) in Nigeria act in partnership with the state but operate directly in the community.4 He argues that some MNOCs actually “govern” local communities by exercising power and allocating resources and by influencing local and national decisions. These MNOCs may work in conjunction with the central authorities or may overshadow them completely. Similarly, Onishi (1999) writes how MNOCs can carry out state-like roles, including the provision of services and facilities of education, agriculture, health and water.5 Other scholars within forced migration literature (e.g. Jeff Crisp and Amy Slaughter 2009; Michael Kagan 2011) have hinted at the concept, as will be examined in the next chapter, but none has related their findings to IR theory on IOs.6

Perhaps the most relevant scholarship to the concept of domestication considered here is Robert Latham’s (2001) research on transterritorial deployments. He looks specifically at where international, global and transnational actors bump up against political and social life “on the ground.”7 According to Latham, transterritorial deployments are “hinges joining global and local forces around the exercise of power and responsibility and the pursuit of political projects across boundaries.”8 Transterritorial deployments are externally based, meaning they have “relatively thick organic links back to some outside point of origin” and usually involve “the purposeful forward placement of a unit, division, or representative of an organization or institution in some local context.”9 By definition, they are specialized in relation to any local...