- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Assembling Çatalhöyük

About this book

"Assembling Çatalhöyük, like archaeological remains, can be read in a number of ways. At one level the volume reports on the exciting new discoveries and advances that are being made in the understanding of the 9000 year-old Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük. The site has long been central to debates about early village societies and the formation of mega-sites in the Middle East. The current long-term project has made many advances in our understanding of the site that impact our wider understanding of the Neolithic and its spread into Europe from the Middle East. These advances concern use of the environment, climate change, subsistence practices, social and economic organization, the role of religion, ritual and symbolism. At another level, the volume reports on methodological advances that have been made by team members, including the development of reflexive methods, paperless recording on site, the integrated use of 3D visualization, and interactive archives. The long-term nature of the project allows these various innovations to be evaluated and critiqued. In particular, the volume includes analyses of the social networks that underpin the assembling of data, and documents the complex ways in which arguments are built within quickly transforming alliances and allegiances within the team. In particular, the volume explores how close inter-disciplinarity, and the assembling of different forms of data from different sub-disciplines, allow the weaving together of information into robust, distributed arguments."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Assembling Science at Çatalhöyük

Interdisciplinarity in Theory and Practice

INTRODUCTION

Within archaeology, the term ‘assemblage’ has a long and central history, though it has perhaps not been theorized as much as other terms. The notion that artefacts are associated together in assemblages within contexts has always been the key that separates archaeology from antiquarianism. If the associations of traits in assemblages are recurring, archaeologists are able to identify cultures, time horizons, elite and non-elite graves, functional tool kits, and so on. The underlying idea is that an artefact found with other artefacts within an assemblage can be interpreted in terms of these other artefacts, and vice versa. Assemblage is thus a building block of archaeological method and theory that allows us to gauge the date, function, type, meaning of objects. But this building block is relational and contextual; relational because one find is interpreted in terms of others, and contextual because the specific set of associations can be related to stratigraphic and spatial information beyond the assemblage itself.

Without assemblages archaeologists would not be able to work out the environment of a site, its economy, or social organization, they would not be able to date many contexts or understand the relationships between sites. Without context and assemblage, there is little to archaeology beyond collecting objects. But there are problems in the definition and interpretation of assemblages (Binford, 1982; LaMotta & Schiffer, 1999; Bailey, 2007; Lucas, 2008). When does a cluster of artefacts become an assemblage? What is the relationship between palimpsest and assemblage? Do we find assemblages or do we actively construct or assemble them? And are clusters of arte-facts intentional associations or unintentional relations produced by depositional or post-depositional processes? And if intentional, what types of intention (conscious or non-discursive etc.) are involved? And who made the association; for example, are the associated artefacts in a grave the assemblage of the deceased or of the living? So, in archaeology, the notion of assemblage raises questions about the processes of assembling. An assemblage is not self-evident.

It is perhaps unfortunate then that the term has been so little theorized in archaeology (see, however, the online Sheffield graduate journal of archaeology called ‘Assemblage’). In contemporary social theory, on the other hand, there is an active and important discussion of assemblage. This theoretical debate deals less with the associations of past artefacts in contexts and more with the production of knowledge—that is with the ways that statements are based on assembling bits of information from divergent sources. It is primarily in this sense that the term is used here, though clearly there is a connection between how archaeologists assemble arguments and how past social actors constructed assemblages. Taylor (1948) argued for a conjunctive approach and I have argued for a contextual approach (1986); in both cases interpretations are based on associations of objects in past assemblages and contexts. But how exactly are theoretical arguments based on these contextual associations? I have argued that archaeologists follow a hermeneutic approach (Hodder, 1999) while Wylie (1989) has argued for a tacking to and fro between different types of data in order to build arguments.

The twenty years of research conducted by the current project at Çatalhöyük allow investigations into how archaeologists assemble arguments by moving between different types of data. Can current social theories about assemblage contribute to an understanding of the archaeological process? Whether it is the work of Latour (2005) on ‘Re-assembling the Social’ or the ideas of Deleuze and Guattari (Deleuze, 2004) and their influence on DeLanda (2006) and Bennett (2009), does the social theoretical discussion of assemblage throw light on the Çatalhöyük research experience?

What are the inflections of meaning that are given to ‘assemblage’ in this social theoretical debate? According to DeLanda (2006), assemblages refer to heterogeneous entities that are not holistic. Assemblages come about historically and have both stabilizing and destabilizing components (that he calls territorialization and deterritorialization). The focus in DeLanda’s assemblage theory is not on essential categories like city or government or person, but on their emergence in specific historical circumstances and on their maintenance. For Marcus & Saka (2006: 101), ‘assemblage … permits the researcher to speak of emergence, heterogeneity, the decentred and the ephemeral in nonetheless ordered social life’. The components of assemblage described by Bennett (2005) are as follows. Assemblage is (1) an ad hoc grouping that comes about historically. (2) Its coherence co-exists with internal counter energies. (3) Assemblage is a web that is uneven and power is differentially distributed. (4) It is not governed by a central power. (5) Assemblage is heterogeneous, made up of different types of actants, human and non-human.

ASSEMBLING ÇATALHÖYÜK

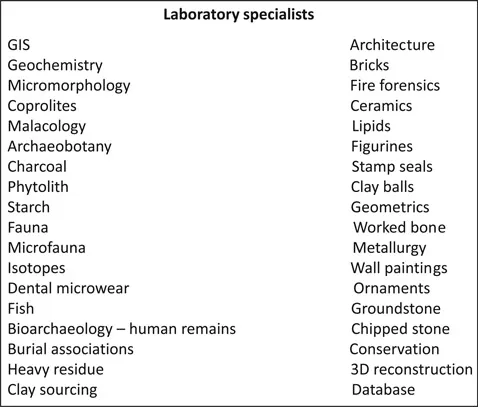

To explore whether these notions of assemblage apply to the research conducted at Çatalhöyük, the project’s working practices need to be explained (Hodder, 2000). As in any large archaeological project, there are a lot of different specialisms. There are one hundred and sixty people currently working on the team—dividable into excavation teams and pods, and there are laboratories in which thirty-six specialisms work (listed in Figure 1). The team members in these different specialisms are brought into conjunction through working together on site, through the ‘priority tours’ where lab members choose priority units together with the excavation pods every second day, through use of a common data base, through writing together in themed volumes, through social events and venues on site, and in some cases through reading each other’s online diaries etc. Within these interactions there are lots of tensions. For example, a major tension has been described elsewhere (Hamilton, 2000) between excavators and lab teams. And there are also fault lines between those specialists more based in the natural sciences and those more engaged in cultural data—I have described elsewhere the ways these different specialisms work (Hodder, 1999).

Figure 1. The main groupings of scientific specialists working on the material excavated from Çatalhöyük.

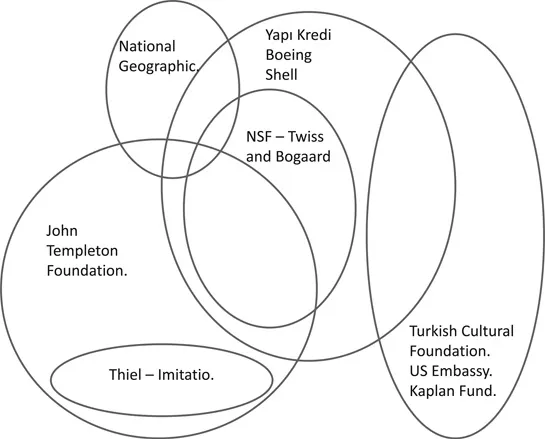

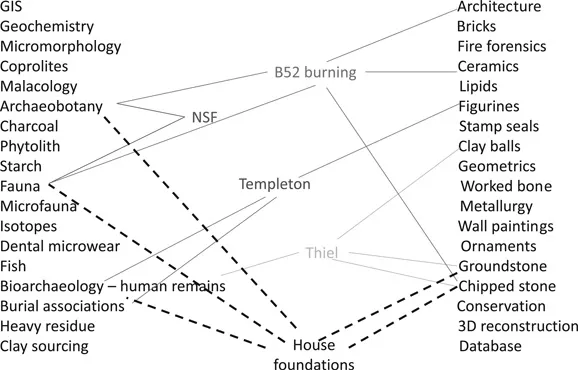

While I as Director make decisions about team membership, and have made major changes to the team on two occasions over the twenty years of the project, and while some will argue that I am a tyrannical and despotic director, the overall research structure is in my view quite flat. There are overall research questions—such as the overarching statement that the project aims to place the art and symbolism within its full environmental, economic, and social context. There has been an overall shift through time from the study of individual houses and depositional processes to the study of the settlement’s social geography. But I as Director play a small or remote part in many research groupings, and a wide range of specific questions have also been asked by different team members, often related to the different profiles and interests of funding bodies. Figure 2 shows the main research interests of different funding bodies that have supported the project over recent years. The research goals do not coincide. By working with these different funding bodies, team members have been pulled in different directions. So, for example, the Templeton Foundation that focuses on religion has drawn in Lynn Meskell and myself on symbolism, Carrie Nakamura on placed deposits, and Lori Hager on the interpretation of a particular burial. Funding from the Thiel Foundation and Imitatio focuses on the relationships between real and symbolic violence and has drawn in bioarchaeologist Chris Knusel regarding evidence of violence on human bodies, groundstone specialist Christina Tsoraki to explore the role of mace heads, and the chipped stone team regarding the function of bifacially flaked points and daggers. National Science Foundation funding was obtained by Kathy Twiss and Amy Bogaard for faunal and botanical studies relating to the question of economic integration and cultural survival at Çatalhöyük. Another group has written about the issue of burning in B52 and whether the fire was caused intentionally or was an accident—this issue has brought in Kathy Twiss and Nerissa Russell from faunal the laboratory, Amy Bogaard and Mike Charles from the botanical laboratory, members of the excavation team including Shahina Farid, Tristan Carter from the chipped stone lab, Nurcan Yalman from pottery and Mira Stevanović from architecture. There are many other examples documented in our themed volumes and in this new volume, sometimes related to funding opportunities, but often just resulting from shared fascination with sets of data that people come to notice fit together or that create interpretive puzzles or problems. The network that put together the ‘house foundation’ paper for this volume (chapter 8) is shown in Figure 3. A fuller account of these networks and a more adequate description of their working are provided by Mickel and Meeks in chapter 3.

Figure 2. Overlaps between the research interests of the different funders at Çatalhöyük.

Figure 3. Specialist groups and their research networks.

It sometimes seems that if up to four to six types of data can be assembled by these groups in such a way that they align and give the same answer, the interpretation appears robust and persuasive. These groups with more fits are more likely to persuade other groups in the team and beyond. A good example is the evidence for increased mobility in the upper levels of the East Mound, as discussed in this volume by Sadvari et al. (chapter 12). The evidence for increased mobility is based on at least seven strands of evidence—the cross-sectional geometry of human femurs, Phragmites encroachment near the site (indicating people had to travel farther from the site), pottery production that increasingly used non-local clays, sheep isotope data suggesting wider use of the environment including C4 plants, obsidian data indicating the use of sources in eastern Anatolia, beads and groundstone items produced from a wider range of distant sources. It seems that strong arguments can be made by boot-strapping different types of data so as to assemble a coherent and persuasive argument. But it should be noted that each one of these types of data could be interpreted differently. For example, the use of more distant pottery, groundstone, and obsidian sources may have nothing to do with increased travel across the landscape but could result from exchange. Each individual strand of evidence is interpreted in relation to the other strands, even if they are quite weak, such as the only marginally statistically significant results on the cross-sectional geometry of human femurs. The idea of boot-strapping or assembling seems appropriate. A theory is produced in the pulling together of different types of data as things are made to cohere. Assembling is an active process that is relational. Everything depends on everything else. In this case, if cross-sectional geometry had shown that human femurs showed less mobility over time, the artefact sourcing data could be re-interpreted in terms of exchange rather than movement.

Sometimes the coming together and assembling into a coherent argument does not work for long—and the project has been going long enough to see the rise and demise of certain theories. Earlier reconstructions of the environment around the site by Neil Roberts and Arlene Rosen had envisaged sufficiently wet conditions that agricultural fields would have been located 12–13 km to the south on drier terraces (Roberts & Rosen, 2009). This reconstruction was based on sedimentological and dating studies of cores taken around the site by Neil Roberts and his team, and on studies of phytoliths by Arlene Rosen that suggested that crops had grown in a dryland environment. New more intensive coring work (by Chris Doherty and Mike Charles), however, has suggested that Çatalhöyük was situated in an undulating and diverse environment, in a marl hollow rather than on a local rise in topography (Charles et al., 2014). A fragmented mosaic is envisaged with higher hum-mocks interspersed with connecting water channels. Within this diverse environment both wetland and dryland resources were exploited and at least some fields could have been near the site. This new hypothesis is based on strontium isotope studies of plants found at the site, on arable weed taxa found in the archaeobotanical assemblage, on studies of seeds in sheep dung, on faunal remains composition, on oxygen isotope and dental microwear studies of sheep and on studies of larger samples of phytoliths (by Philippa Ryan). Thus at least eight strands of data seem to come together to make a strong new argument. But it is also undoubtedly the case that the team has come to accept this new hypothesis as making more sense in relation to wider expectations. There was a worry that it just did not make sense to have fields far away from the site, and there is strong within-group peer support for a more usual scenario that also fits with previous publications by current team members. It should be noted that Neil Roberts argues that at least some of the new identifications and reinterpretations made by the current team are mistaken and that aspects at least of the old model should be retained. In the end it seems that even the identification of a ‘back swamp clay’ is an interpretation that can be contested and re-interpreted in relation to other data.

There are many other examples of ideas that have emerged informally among team members. For example, early on we started using the very unhelpful and ill-defined term ‘dirty floors’ to describe a type of floor we saw in the southern parts of main rooms in houses. This was initially just a short-hand that circulated in the group to describe a difference between clean and dirty that we noticed. But it became hardened and has even now entered the literature with elaborate definitions and numerous analyses and studies that quantify and demonstrate the difference (Hodder & Cessford, 2004). The notion that there are different types of midden emerged in the same way. The idea of history houses suddenly emerged in a Templeton seminar in the seminar room on site (Hodder & Pels, 2010) and has grown to dominate our research even though the category remains elusive and unclear. In all these examples we see ideas emerging within various forms of network—whether ad hoc and informal or funded and ‘official’; the ideas either grow or die in the networks. The networks often have social components, based on peer groups that like working together or see strategic advantage in working together, but they ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 Assembling Science at Çatalhöyük

- CHAPTER 2 Representing the Archaeological Process at Çatalhöyük in a Living Archive

- CHAPTER 3 Networking the Teams and Texts of Archaeological Research at Çatalhöyük

- CHAPTER 4 Interpretation Process at Çatalhöyük using 3D

- CHAPTER 5 Reading the Bones, Reading the Stones

- CHAPTER 6 Reconciling the Body

- CHAPTER 7 Roles for the Sexes

- CHAPTER 8 Laying the Foundations

- CHAPTER 9 The Architecture of Neolithic Çatalhöyük as a Process

- CHAPTER 10 ‘Up in Flames’

- CHAPTER 11 The Nature of Household in the Upper Levels at Çatalhöyük

- CHAPTER 12 The People and Their Landscape(s)

- CHAPTER 13 The End of the Neolithic Settlement

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Assembling Çatalhöyük by Ian Hodder,Arkadiusz Marciniak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.