![]()

CHAPTER 1

From Idea to Parameter: Good Copies

William Blake never left England but it is likely that he was well aware of the body model promoted by Johann Caspar Lavater. In the 1790s the two main factors of the European context of the early illuminated books are Blake’s friendship with Henry Fuseli and the engraver team working on Henry Hunter’s translation of Lavater’s physiognomy, Essays on Physiognomy (1789–98).1 Lavater’s physiognomy, with its analyses and interpretations of facial features, first appeared in German in the 1770s. ‘The greatest attraction of the Physiognomische Fragmente’, writes Robert E. Norton, ‘arose naturally from the intrinsic appeal of the subject itself: the practice of discerning a person’s true character on the evidence presented by external appearance alone, and above all by the face.’ Lavater promised that readers ‘would learn to decipher their neighbors’ inner beings by scrutinizing their outer shells’.2 Learning how to read a face would have been especially difficult for Lavater’s British audience since the final section of the project was never translated into English. But Blake, by way of his friendship with Fuseli, could have learnt more than most. Blake may also have known Thomas Holcroft, who translated a rival edition of 1789 and was chief editor of The Wit’s Magazine in the early 1780s, when he did engravings for this magazine.3 Working for Fuseli and on the Hunter translation introduced Blake to new relationships between text and image as well as original and copy.

Lavater’s influence on Blake’s thinking can best be seen in the creation myth. His version of the Biblical creation myth focuses not on the creation of the world and the creatures within it, but on the creation of man and on how the human prototype acquires individual features. Building on Jerome McGann’s research into the historical context of Blake’s reading of the Genesis story, this book argues that Essays on Physiognomy is an unacknowledged precursor to the theme and structure of Urizen. McGann reviews the work of Northrop Frye and Leslie Tannenbaum in order to propose that the way in which the narratives of the myth ‘intertwine’, and how its two creator gods, Urizen and Los,4 relate to each other, is a direct response to contemporary research into textual authority and authenticity. McGann locates Blake firmly in the Joseph Johnson circle and argues that he may have learned about the ‘documentary hypothesis’ through the Roman Catholic Alexander Geddes, who read German Higher Criticism and developed his own ‘fragment hypothesis’ about the Pentateuch.5 With regard to the creation myth McGann stresses that Geddes went one step further than his German counterparts: for Geddes the Bible ‘is not so uniformly layered’ but is ‘a heterogeneous collection of various materials gathered together at different times by different editors and redactors.’6 The research into the context of Blake’s work and ideas continues. In this book I will demonstrate how the problems occurring during the production of the Hunter translation as well as Aphorisms on Man can be seen to resonate in Blake’s adaptation of the Genesis story.7

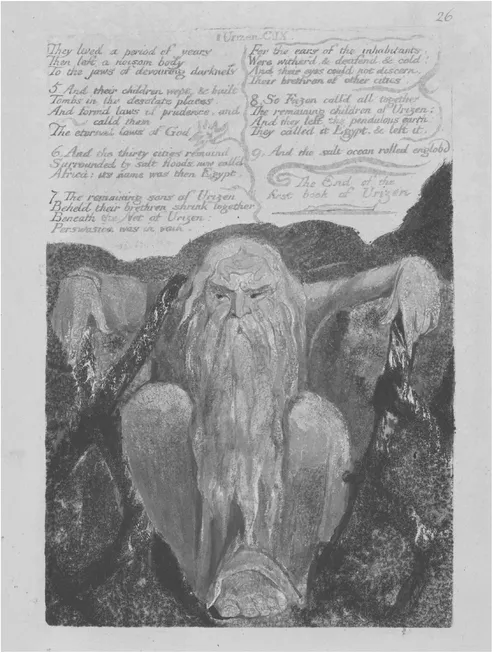

Lavater thought of his physiognomy as incomplete and unfinished. Even the author’s preface he regarded as work-in-progress: ‘The Work which I present to the Publick being only a series of Fragments, my Preface too must come under that denomination; I give it only as a Fragment. I cannot compress all I have to say within the compass of a few pages’ (EoP, I, n. p.). Each section can be continued and developed by adding more data and more comparisons; it is the notion of open-endedness, associated with the literary form of the fragment, which turns this project into a multidirectional text. Blake’s creation myth is similarly diverse. It begins with Urizen and develops into two more books, The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los. The eight surviving copies of Urizen range from twenty-four to twenty-eight text and picture plates and not all copies have the word ‘first’ on their title page.8 There is no one core text. All this complicates the textual status of the work but, at the same time, makes this book unique in Blake’s oeuvre. Urizen was printed in an edition of probably six copies in 1794, all of which were colour-printed, then re-issued in 1795 and printed again in 1818.9 What links the different books is that sections of the creation plot are retold. This repetition is instrumental to Blake’s parody of likeness-making in Genesis. In McGann’s words, ‘These passages do not locate authorial lapses or errors or unresolved incoherences, they represent deliberate acts on Blake’s part, textualizations which make Urizen a parody of Genesis.’10 Late eighteenth-century commentary on the Bible targets state authority, because from the examination of textual authority it is but a small step to questioning the traditions by which a government justifies its legislation. Probably the best example is Tom Paine’s The Age of Reason (1794–95). This continues the themes of freedom and political justice of The Rights of Man (1791–92), written in response to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790). In The Rights of Man Paine attacks Burke by deconstructing the medieval and religious sanction of Burke’s warnings against a French-style revolution. Paine is adamant: Burke is wrong to ignore the question of Parliamentary representation.11 David Worrall, editor of the Tate Trust Facsimile edition of The Urizen Books, argues that Blake was drawn to the Biblical creation myth because of the challenges posed by the influential deistic narratives which began appearing in the 1790s, principally the work of Tom Paine but also François Constantin Volney’s Ruins: Or, a Survey of the Revolutions of Empires, available in English translation from 1791. Worrall writes:

Whatever the final truths about the importance of Blake’s cultural context, there can be little doubt that the main purpose of Urizen is to show how Blake’s contemporary ‘brethren’ and ‘Inhabitants of ... Cities’ (‘citizens’, in the period’s Jacobinical nomenclature), have become enslaved and ‘weaken’d’ by the ‘Net of Reli-/-ion’. To show how this has come to pass, Blake transforms the Christian scripture into a myth (the myth of Urizen) which lacks Christianity’s political establishment and authority.12

But Blake, I think, changes the Genesis story almost beyond recognition. His creation myth juxtaposes versions of creation, that is, it repeats and retells the parts of the plot which deal with the creation of the human body. As a consequence, rather than making a cohesive statement about creation, Blake interrogates the idea that ‘God created man after his own likeness’.13 We would assume divine creation to be effortless and perfect, but in Blake’s version the focus is on the struggles which the different figures, the creator and the created, have to overcome in acquiring their recognizably human bodies. Blake takes us back to the origin of likeness-making.

In Urizen, the creation of man is no celebration. What should have been the embodiment of divine likeness turns out to be a lesser version of the original. Blake’s treatment of the Biblical creation theme is an important example of his response to a specifically European manifestation of a wider Enlightenment aesthetic movement, one which provided an interpretation of the body’s relationship to the soul. Blake’s creation myth probes deeply into the dynamic construction of human identity, because, like no other of his works, Urizen raises important questions about accuracy and the production of true likeness. This poses the question whether Blake conceived his creation myth as a testing ground for the potentials and limitations of the so-called science of character. The most direct attack on Lavater’s approach appears on plate 21 of Urizen. When Blake describes Urizen’s achievements, he satirizes them:

And his world teemed vast enormities

Frightning; faithless; fawning

Portions of life; similitudes

Of a foot, or a hand, or a head

Or a heart, or an eye, they swam mischevous

Dread terrors! delighting in blood.

(E 81; BU, Pl. 21, ll. 2–7)

Something has gone badly wrong. Urizen's world is full of creatures but does not teem with life. If carried too far, likeness-making turns into a dissection. In Urizen, life is substituted by a bloodbath filled with half-dead and looking-as-if-alive body parts.14

Blake was a trained copy-engraver. In ‘Blake and the Traditions of Reproductive Engraving’ (1972) Robert N. Essick describes how Blake, trained in the mode of an eighteenth-century engraver, would have used established conventions when engraving the human form. In traditional commercial engravings objects are represented with the help of parallel as well as hatching lines. Due to their different depths they produce the illusion of tone. Essick terms the line system at the disposal of an engraver a ‘visual syntax’ and suggests that it is as a barrier between the viewer and the object: ‘The system [...] reduces all objects to a linear “net” or “web” [...] beneath which the objects reproduced almost disappear [...] an abstract network of lines, which at once both delineates and entraps the human forms represented.’ Essick concludes that the ‘abstracting processes of reproductive engraving [have] become basic metaphors in a myth of creation, Fall, and entrapment’.15 Essick offers a very suggestive interpretation of the meaning embedded in the dot and lozenge engraving technique which, effectively, materializes the human body through a process which appears to entrap spiritual qualities within the technology of its own expression.16 Blake may have felt compelled to develop the relief-etched techniques employed in the illuminated books.17 My work also draws on the research of Saree Makdisi who, in William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s (2003), takes a Marxist approach when examining the economic and aesthetic contexts of Blake’s ambition to create true art. Makdisi discusses how networks18 of social codes organize or rather regulate the identity of the individual as well as the community around it:

the subject can also be recognized as a form of imprisonment, confinement, and restriction as deleterious as occupational confinement in a productive industrial organization. In contrasting the deskilled journeyman with the skilled craftsman, in other words, Blake was contrasting two forms of social, political, and religious organization, not just two levels of productive skill or two ways of producing art [...]. Art, society, economics, politics, and religion must be seen here as one continuum, not segregated areas of activity.19

I agree with Makdisi, who uses Urizen as a case study to argue that repetitive actions — rather than individual creational acts — give shape to human identity, but I want to compare Lavater’s use of the silhouette with Blake’s use of ‘The Net of Religion’ (Fig. 1), which at the end of Urizen — so the narrator tells us — pours out of Urizen’s body, because I think it important to consider the literal as well as the physical dimensions of embodiment: ‘The Net of Religion’ really does create physical reality by physiognomically embodying the identity of others.

One of the reasons the physiognomy project is so important to Blake’s professional development is that the advertising campaign promoting the Hunter translation revolved around the issue of good copy-making. In 1789, the year Essays on Physiognomy was launched, volume IV of the French translation, Essai sur la physionomie, was still outstanding. In the advertisement Fuseli20 claims that the Hunter translation is a complete edition and perfect copy of the French edition.21 Fuseli, of course, could not have foreseen that the French edition was going to be interrupted by the French Revolution. When volume IV of Essai sur la physionomie finally appeared in 1803, Heinrich Steiner, a Swiss publisher, apologised for the delay but also revealed something which is symptomatic of the whole of the work’s publishing history. Steiner explained that despite the first prospectus’s promise, they had decided to publish an additional fourth volume which they planned to issue by the end of 1788. The necessity for an extra volume, he said, arose from six chapters which could not be incorporated into the already very thick volume III — the reason being that Lavater insisted that more engravings, more than originally agreed on, be included. The additional volume was to be given to the subscribers ‘gratis’. To ensure that this new volume should be as extensive as the other volumes, Steiner also revealed that Lavater was commissioned to write a résumé (EsP, IV, n. p.).22 Volume IV was never translated into English and the Hunter translation is, therefore, incomplete. Whereas the first German edition, Physiognomische Fragmente, ends with a two-page conclusion, the Hunter translation stops abruptly. Those working on the Hunter translation would have quickly realized that the French

FIG. 1. Blake, The Book of Urizen, Copy D, plate 26

(© Trustees of the British Museum)

edit...