![]()

Chapter 1

Orator to the Artists: Gautier and Pradier in 1848

Cher Théophile,

Faites donc encore une fois entendre à l'autorité la voix des artistes qui se désolent, vous qui êtes leur orateur et qui les soutenez si noblement. Le salon est fermé et point encore de nouvelles d'acquisitions par le Ministre l'an passé c'était la disette qui était la cause de la rentrée de nos ouvrages qui dorment encore dans nos ateliers aujourd'hui c'est la république qui ne s'en soucie guère qui gâche et avale tout...

Montpellier, désirant avoir ma statue de Nissia pour son Musée j'ai prié le ministre de la prendre pour le prix qu'il voudrait mes dépenses seulement point de réponse, un silence mortel règne dans ce misérable Ministère qui devrait songer que nous n'avons même plus la liste civile pour nous aider, pauvres arts relégués avec la police pourquoi cette administration n'est-elle pas avec sa soeur les lettres j'en suis avili et le courage me manque /.

Notre tout affectionné

J. Pradier

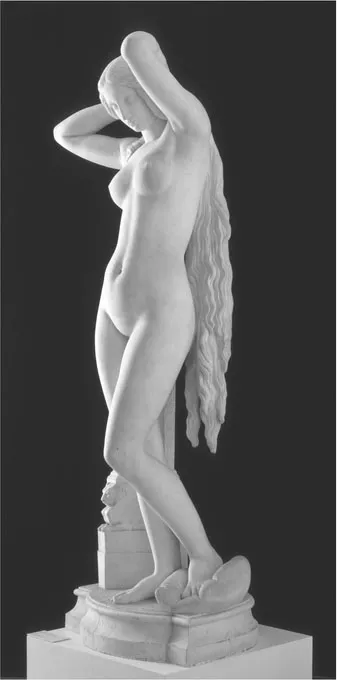

This letter to Gautier from the Swiss-born French sculptor James Pradier, from which the title of this study is taken, was one of a number he wrote during the first summer of the Second Republic to draw attention to his financial plight and that of artists in general. The annual Salon had closed its doors at the beginning of July and Pradier was trying to secure the sale to the State, for the museum in Montpellier, of one of the works he had shown there, his marble statue Nyssia (Figure 1.1).1 Gautier had good reason to be interested in the statue's destination since Nyssia was the heroine of his short story of 1844, Le Roi Candante, a brief extract of which was quoted in the Salon catalogue as the source for the work.2 He was not by any means the only one whose support Pradier sought to enlist that summer in his efforts to achieve the sale. Others included Hugo, who, like Gautier, was a long-standing friend, and Charles Blanc, Directeur des Beaux-Arts since the beginning of April that year and, as such, responsible in the Republican administration for the commission and purchase of art works. Since that year more than ever the government was taking an active interest in the fine arts, Pradier for good measure also contacted Antoine Sénard and General Louis Cavaignac, who, in the view of the National Assembly, 'avaient bien mérité de la patrie' during the bloody events of 23-26 June 1848 and had been duly rewarded for the key parts they

FIG. I.I. James Pradier, Nyssia, 1848, Montpellier, Musée Fabre © Musée Fabre, Montpellier Agglomération, cliché Frédéric Jaulmes

played in the brutal suppression of the insurrection that week with promotion to the posts of Minister of the Interior and Président du Conseil respectively.3 With this level of support, it was perhaps not surprising that Pradier's efforts Soon paid off. On 19 August Charles Blanc informed him that the State, in the person of the Minister of the Interior, had agreed to purchase Nyssia for ten thousand francs and to authorize its transfer to the museum at Montpellier.4

It is not known whether Gautier responded to Pradier's request to intervene on his behalf,5 but what is clear is that, as a target for recruitment to the sculptor's sales drive alongside France's two most powerful politicians (albeit briefly), its most senior arts administrator, and its greatest living poet, Gautier was in distinguished company. In Pradier's designation of him as orator to the artists, allowance must of course be made for self-serving flattery, but as a description of Gautier's status in art journalism by that time, as an indicator of the speculative value his name had acquired, this quasi-official title was close to the mark. By then he had been France's best-known art journalist for over a decade, during which time he had given artists ample evidence of his loyalty, support and willingness to use his art journalism to further their professional interests. He knew the French fine arts system, its administrative structures and key personnel, he knew his art history, ancient and modern, he was familiar with the materials and processes of the visual arts, with the language of the studios and the tricks of the trade. Writing for the newspaper created by one of the most powerful figures in the French press of the nineteenth century, he combined erudition and exceptional verbal facility and range in ways well attuned to the new reading public that had emerged during the July Monarchy. The change of regime triggered by the revolution of 1848 created challenges and opportunities for the skills he had acquired and for the relationships he had nurtured since beginning to write art criticism in the early 1830s.6 These skills and relationships, the part they played and the purposes to which they were put during the Second Republic, will be the Subject of what follows.

To introduce the issues involved, we may continue our annotation of Pradier's letter to Gautier. In the summer of 1848 Pradier was fifty-two years old and had a long and distinguished career behind him. He had followed the French path of competitions and promotions to the summit of his profession: 1813, winner of the Grand Prix de Rome for sculpture; 1827, member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts and Professor at the École des Beaux-Arts; 1828, Légion d'honneur, promoted to the rank of Officer six years later. His work had been regularly accepted by the juries of the Paris Fine Art Salons from 1819 onwards and he had secured a steady stream of commissions and Sales from both the Bourbon and the Orleanist administrations.7 If in 1848 Pradier needed a concerted and high-powered campaign to enable him to translate his longestablished professional eminence into the hard currency of a sale, what can it have been like for the others, those with less of a career behind them or with less access to the people who mattered? What could the immediate future hold for them?

One F. de Lagenevais, in his review of the Salon of 1848 for the fortnightly Orleanist Revue des deux mondes, had an answer of sorts to that question, but one which would have brought little comfort to Pradier. Referring to artists in general he wrote:

La crise financière leur sera sans doute fatale: le niveau de fer qui pèse sur tant d'existences doit briser le pinceau et l'ébauchoir dans la main de plus d'un homme de talent. Les jours difficiles vont commencer. Les encouragemens que les particuliers accordaient aux artistes, et qui ne sont que l'emploi du superflu que bien peu possèdent aujourd'hui, vont leur manquer. Les nombreuses médiocrités qui vivaient de ce superflu sont donc condamnées à périr; n'ayant pas foi dans l'art, elles le délaisseront et se réfugieront dans d'autres carrières plus profitables. Les vrais artistes lui resteront seuls fidèles dans ces jours d'épreuves et partageront ses destinées. Le sort de ces hommes dévoués devra inspirer à l'état une juste sollicitude.8

F. de Lagenevais was a pseudonym for Frédéric de Mercey, who in 1S40 had been appointed chef de bureau in the Fine Arts division of the July Monarchy, and who had, in a seamless transition, retained the same responsibilities under the Second Republic. One of his tasks was to read the begging letters from artists which, during the summer of 1848, were arriving on his desk in greater numbers than ever and to make recommendations to Charles Blanc on the choice of artists to receive commissions and art works to be purchased. His comments were, therefore, an assessment by one of the most senior managers in the Fine Arts administration of the likely impact on the fine arts of the financial difficulties that the country was experiencing in the months following the revolution. As a good Orleanist economic liberal and social conservative, he believed that with private buyers abandoning the art market in droves, its collapse would at least have the beneficial effect of persuading the 'numerous mediocrities' within the artistic community to look for other careers. If those of weak vocation went to the wall, the state would be in a better position to support artists of talent and achievement more deserving of its munificence. This final comment might have been expected to improve Pradier's morale, but in his letter to Gautier he clearly despaired of the government's will and means to sustain the market during a period of crisis. As Pradier knew well and as we shall see, state patronage of the arts was an issue close to Gautier's heart, one which had already featured prominently in his art journalism that year.

Among artists and within the arts media, there was no shortage of support for Pradier's grim assessment of the position in which artists found themselves by the summer of 1:848. While recognizing the good will, 'stérile il est vrai (faute sans doute de l'argent)', of the Bureau des Beaux-Arts, L'Artiste published on 1 June an extract of a petition, allegedly 'signée d'un grand nombre d'artistes', stating that painters were having to sell their palettes and sculptors their knives at the very time the government was creating four posts of inspector of provincial museums at an annual cost of twenty-four thousand francs each — the usual story, in other words, of jobs for the bureaucrats while the artists starved.9 A fortnight later in the same journal an anonymous editorial accused the administration of having betrayed the artists' support for the republic and of treating them with the sort of mistrust that was directed at the workers in the doomed ateliers nationaux:

Lés áteliers, où la misère et le désespoir ont élu leur domicile, ce sont pour la plupart les ateliers de peinture et de sculpture. Il y a là des douleurs qui se cachent et qui n'espèrent plus en la République. Et pourtant les artistes ont crié: Vive la République avec tout l'accent du cœur, quelques-uns avec des armes triomphantes. Plus d'un artiste républicain en est à se rappeler avec un sentiment de reconnaissance le temps où il allait fumer à Vincennes quand M. de Montpensier, après lui avoir acheté un tableau, l'y appelait en toute liberté, égalité et fraternité; car M. de Montpensier était un démocrate de la république des arts, si on le compare aux parvenus de la veille qui traitent les artistes comme les ouvriers des ateliers nationaux, c'est-à-dire comme une canaille inquiétante suivant leur expression.10

These were the artists whom Gautier in euphoric mode had urged to seize the time and realize the vision of a democratic Republic of the Arts. 'Si vous le voulez', he had told them, 'que seront à côté du nôtre les siècles tant vantés de Péricles, de Léon X et de Louis XIV. Un grand peuple libre pourra ι il moins pour l'art qu'une petite ville de l'Attique, un pape et un roi?'11 Within hours of coming to power the Provisional Government appeared to have given itself the means of its ambitions through its annexation of the Civil List, whose remit, including the budget for the purchase and commission of art works shown in the annual Salon, had been removed from the defunct Maison du Roi and placed under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior, henceforth to be accountable to an elected National Assembly.12 Yet here was the government being accused only three months later of succeeding only in rehabilitating in the eyes of artists the royal patronage of the arts under the July Monarchy (the duc de Montpensier was Louis-Philippe's fifth son and the château de Vincennes his official residence), such was its betrayal of even its own supporters among the artists.13 The money formerly spent on the arts via the Civil List seemed to have vanished down the black hole of public finances.14 As someone who had cultivated his connections with the royal family and entourage during the July Monarchy to secure commissions and sales, Pradier felt the loss of the Civil List keenly, as his comment to Gautier shows. Gautier felt it too, but because he, unlike Pradier, supported the republic.15

The loss of the Civil List was just one of the potential resources threatened, as far as Pradier was concerned, by government incompetence and inertia. Another was a strategy he had been pursuing since the early 1840s, when he had begun to cultivate relationships with curators and local artists, writers, and dignitaries in his home region of Provence, so as to broaden his market base and reduce his dependence on the increasingly competitive Parisian market for commissions and sales.16 This objective had taken on greater urgency in 1847, when Clésinger's Femme piquée par un serpent had caused a sensation in the Salon. Gautier in particular had been very enthusiastic, a sure warning sign for Pradier.17 It is clear that he felt threatened by the newcomer whose voluptuous nude appeared so much more audacious in its modernity than his own hitherto very marketable synthesis of antique and modern nudes.18 In 1848, Clésinger's follow-up, La Bacchante, accompanied by another very positive Gautier commentary, had confirmed the threat.19 At a time when few sculptors could afford to work in the noble materials of marble or bronze except to order, Pradier had assumed the financial risk of sculpting his Nyssia directly in marble without a buyer lined up in advance.20 He would therefore have been anxious at the best of times to conclude the sale of the work, but with the emergence of a powerful rival in Paris combined with the dire straits in which the market...