- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

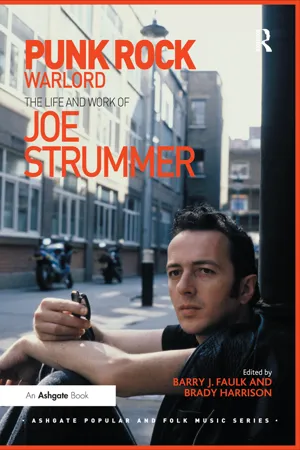

Punk Rock Warlord: the Life and Work of Joe Strummer

About this book

Punk Rock Warlord explores the relevance of Joe Strummer within the continuing legacies of both punk rock and progressive politics. It is aimed at scholars and general readers interested in The Clash, punk culture, and the intersections between pop music and politics, on both sides of the Atlantic. Contributors to the collection represent a wide range of disciplines, including history, sociology, musicology, and literature; their work examines all phases of Strummer's career, from his early days as 'Woody' the busker to the whirlwind years as front man for The Clash, to the 'wilderness years' and Strummer's final days with the Mescaleros. Punk Rock Warlord offers an engaging survey of its subject, while at the same time challenging some of the historical narratives that have been constructed around Strummer the Punk Icon. The essays in Punk Rock Warlord address issues including John Graham Mellor's self-fashioning as 'Joe Strummer, rock revolutionary'; critical and media constructions of punk; and the singer's complicated and changing relationship to feminism and anti-racist politics. These diverse essays nevertheless cohere around the claim that Strummer's look, style, and musical repertoire are so rooted in both English and American cultures that he cannot finally be extricated from either.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Punk Rock Warlord: the Life and Work of Joe Strummer by Barry J. Faulk,Brady Harrison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Musica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

MusicaPart I

John/Woody/Joe

Chapter 1

“Don’t Call Me Woody”: The Punk Compassion and Folk Rebellion of Joe Strummer and Woody Guthrie

Popular opinion holds that Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen are the only legitimate heirs to Woody Guthrie’s legacy, a mantle both singer/songwriters courted, when it suited them. Early association with Guthrie bought Dylan credibility with folk singers like Pete Seeger and Joan Baez. Later, Dylan needed to shuck that association, so he could establish himself as an authentic rock star, like Roy Orbison or Elvis Presley. With 1965’s Highway Sixty-one Revisited, Dylan retired as “voice of a generation”, setting aside political agitation for a lyrical voice that was personal, mystical, religious, literary – almost never topical, political, and radical.

Conversely, Springsteen sought association with Guthrie only after establishing himself as a mostly apolitical rocker. Relatively late in his career, Springsteen built folk cred through forays into acoustic recordings like Nebraska and The Ghost of Tom Joad, and a 1986 live recording of “This Land is Your Land” (sans its radical verses). While Springsteen had performed at the 1979 No Nukes concerts, fans could ascribe to his music virtually any political leaning they chose. Was “Born in the U. S. A.” jingoistic or rebellious? Right wing or left wing? That the song was praised by both Amiri Baraka and George Will (Cowie and Boehm 358–9) testifies to its ambiguity. Springsteen finally put his political capital on the line, endorsing John Kerry in the 2004 presidential campaign, but supporting a major party candidate and career politician was hardly radical, or dangerous. By that time, “The Boss” was a huge rock star with a “Beverly Hills home [which] reportedly cost $14 million”. His music “explored issues of social justice, but he did not seriously question the social system that by his own admission allowed him to lead ‘an extravagant lifestyle’” (Garman 246).

Dylan and Springsteen are unquestionably rock and roll figures of towering significance. Dylan essentially created the rock and roll singer/songwriter and made space in rock music for political agitation. But both had interests other than radicalism. Their songs pursued artistic and aesthetic paths at once personal and profound, unique and influential. They were also careful architects of their careers. When it suited them, they were political; when it did not, they weren’t. They have produced remarkable songs of social conscience, but both have cultivated careers that made use of the Guthrie legacy rather than embraced it in its radical wholeness. No, among the rock and roll generations, Guthrie’s truest heir may be Clash vocalist and songwriter Joe Strummer. Ironically, while Strummer briefly adopted the name “Woody” in his earliest days as a performer, he never cultivated identification between himself and Guthrie, and he dropped the name years before becoming even remotely well known, much less famous. During his peak years of fame, few Clash fans knew that Joe Strummer had once been “Woody Mellor”.

Neither was a true Marxist or Communist, of course; Guthrie famously tossed off the line, “left wing, right wing, chicken wing – it’s all the same to me” (Cray 138). They were artists first and political theorists second, but both could be called truthfully “fellow travelers”. Dylan and Springsteen, like many another singer/songwriter, were more comfortable adopting the guise of “Woody Guthrie as romantic idealist” (Shumway 137) than political radical. David Shumway wrote, “if we are to understand Woody Guthrie’s place in our cultural history, we can only do so by recognizing the indigenous radicalism of his songs” (137), and no rock and roll songwriter of prominence managed to present such a consistently anti-capitalist position through so many phases of his or her career as Joe Strummer. With and without the Clash, he offered through his songs a “Marxist-inflected social critique” (Matula 523) that explicitly took on capitalism. For radicalism, Clash songs like “Washington Bullets”, “Straight to Hell”, and “Know Your Rights” and Strummer solo songs like “Shaktar Donetsk”, “Generations”, and “Get Down Moses” sit comfortably beside even Dylan’s great early songs “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” and “Only a Pawn in Their Game”, to say nothing of “Thunder Road”.

In 1998, when Joe Strummer launched his BBC “Cross-Cultural Transglobal [radio] show” (Salewicz 560),1 one of the first songs he played was Trini Lopez’s mariachi cover of “This Land is Your Land”, Woody Guthrie’s alternative national anthem. For those only passingly familiar with Strummer from the Clash or fans blinded by labels like “punk” and “hippie”, it might have seemed an odd selection, but it was an apt choice. Strummer began his career “singing […] in London’s subways for spare change” (Gilmore 53) with Tymon Dogg as “Woody Mellor”; later, he performed with the Vultures and pub rockers the 101’ers under the same name. Not until 1975 did he adopt “Joe Strummer”, the stage name he kept until his 2002 death. From that point on, “you couldn’t call him Woody – he’d be angry” (Salewicz 127).

Adopting a new identity and obliterating the past was a pattern Strummer often repeated. He left behind his middle-class life to become a hobo-beatnik with the 101’ers, then became a punk rocker and left them to join the Clash. Later, he fired songwriting partner Mick Jones and reformed the most potent rock band in the world as if the personnel were interchangeable, and he really could rewrite the past and the future. Jones called it “Stalinist Revisionism … once you’re out you’re out” (Jones Interview). On his sticky relationship with history, Strummer remarked, “The past is a roomful of treacle. You think you can just walk in and walk out again but you can’t” (“Sound of Strummer” np).

Consider another metaphor. “Woody Mellor” is a fossil excavated from rock and roll history, containing various strata of Joe Strummer’s identity. His given name, “John Graham Mellor”, still visible through the erosion. Also intact is his love of 1960s’ hippie culture and American folk music, not yet sandblasted away by Bernie Rhodes or the passing moment of fashion that was punk rock. The name “exposes his unexplored fantasies of being a folksinger, poet, […] painter, or […] just an interesting beatnik bum” (Gilbert 16).2 In the 2007 documentary The Future is Unwritten, Clash drummer Topper Headon recalls angering Strummer by calling him “Woody” as a lark; Headon had no idea that Strummer began his career modeling himself after Woody Guthrie. Why should he have? Strummer had already “created a mist around his past” (Gilbert 16).

A decade after Strummer’s death, the artistic, familial, personal, and professional parallels he shared with Woody Guthrie are eerie. Family tragedies and radical politics blended for Strummer and Guthrie: both rebelled against their fathers’ middle class politics and social standing. Strummer’s brother committed suicide after joining a neo-fascist group, while Guthrie stood by his sister’s bed and watched her die of self-inflicted burns, inspiring his identification with the powerless. Both enjoyed success as performers of “popular” music (although they would bristle at the term), reinventing themselves as hardscrabble working class heroes, obscuring their middle-class pasts. Tragedy hounded them, and they died of congenital illnesses in their 50s: Strummer at 50 of a heart defect, Guthrie at 55 of Huntington’s Disease.

Both feared and fled from success, rare among show-business figures. When artist Damien Hirst asked, “What’s the biggest thing you’ve ever killed?” Strummer replied, “My career” (Salewicz 467). Guthrie could have offered the same answer. Of course, poor management, a fickle public, and myriad other problems can short-circuit a music career, but neither Strummer nor Guthrie ever had the discipline and determination that distinguish Dylan and Springsteen’s decades-long reigns as rock royalty. Financial rewards were at odds with their proletarian values to a degree that neither Dylan nor Springsteen felt.

Guthrie and Strummer were driven by class (personal ideologies of class, identification with the working class, and even fans’ and detractors’ attitudes toward class), so it is worth considering the parallel tracks they followed from middle class beginnings to their performing careers. Woody Guthrie’s father, Charley Guthrie, was a staunch member of the Democratic Party in early 20th century Oklahoma, when to be a Southern Democrat was to support white rule. The elder Guthrie was an “enthusiastic member” of the Ku Klux Klan, although according to Joe Klein, the Oklahoma branch of the Klan “functioned more as the martial arm of the Chamber of Commerce” (23) than a white supremacist brigade. Still, literacy tests blocked Blacks from voting and ensured the Democratic dominance that paved the way for Charley Guthrie’s election as Okemah court clerk (Cray 8). In Oklahoma, “Jim Crow ruled” (8).

Charley, though, was less concerned with race than with “the rise of the Socialist Party in Oklahoma” (9). He named his son for Woodrow Wilson, who ran for president against Socialist Eugene Debs in 1912. Had Charley heard Woody declare Debs “a pure cross between Jesus Christ and Abe Lincoln” (324), it is likely he would have disapproved. A cursory look at Woody’s life and work demonstrates how thoroughly the son rejected the politics of father. In “All You Fascists”, Woody explicitly links Southern racism, fascism, money, and power: “Your poll tax and Jim Crow/And greed has got to go”. For Woody the Socialist, the end was clear: “fascists [are] bound to lose” (Lyrics). Later, he supplied a song for the quixotic 1952 Florida gubernatorial campaign of muckraking journalist Stetson Kennedy, who had investigated the Klan in the 1940s (Klein 405–406).

Joe Strummer/Woody Mellor/John Graham Mellor had a similarly ambivalent relationship with his father, Ronald Mellor. “John Mellor was born the son of a diplomat and worked as a prefect in an upper-class school” (Matula 524), whereas rock star Joe Strummer got “endless stick about his father’s job […] in the Foreign Office […] one of the most elite and snobbish departments of the Civil Service”. Foreign Office employees were “expected to embody the stiffly conservative values of old Empire” (Gilbert 6). In punk rock, a privileged background was a hanging offense. Ray Davies, the great rock spokesman for the British working class, crystallized the sentiment in the 1976 Kinks song “Prince of the Punks”: “He acts working class but it’s all bologna,/He’s really middle class and he’s just a phony” (Davies “Prince”).

Some went so far as to take Strummer to task for writing the great Guthrie-influenced outlaw song, “Bankrobber”. Critic Tony Fletcher saw in the lines, “My daddy was a bankrobber/but he never hurt nobody” a clumsy attempt by Strummer to pad his resume. Utterly blinded by the specter of class, Fletcher calls the song “preposterous” (46), as if he cannot conceive that one might write from a point of view other than his own, as if all lyrics must be autobiographical. Truly, Strummer’s middle-class background had “repercussions […] throughout his life” (Gilbert 6). Ronald Mellor, however, was no Charley Guthrie; his politics were not that far from his son’s, yet Strummer would spend “years feeling estranged” from his father (6) and mother, largely because “he felt abandoned when he’d been sent off to [boarding] school” (Salewicz 112). Like Guthrie, Strummer spent his teen years separated from parents and family, a separation that left its mark. Sadly, Guthrie and Strummer both lost siblings to gruesome deaths. These youthful traumas forced terrible repercussions on both, although only Guthrie was able to write directly about it.

Clara Guthrie’s death haunted her younger brother. Nora Guthrie, Woody’s mother, by this time was feeling the effects of Huntington’s Disease, which would later claim Woody. Her illness likely spurred the events that led to Clara’s death: “Nora ordered Clara to stay home from school […]. Clara insisted she had to take a final exam that day […]. Finally, the strong-willed Clara spilled kerosene on her dress, struck a match and set it on fire” (Cray 18). As it turns out, dealing with tragic fires became a survival skill for Woody. Ten years before Clara’s death, “sparks from [a neighbor’s] kitchen ignited the Guthrie house” (8). In 1946, Woody’s three-year old daughter Cathy Ann died in a fire in their Coney Island apartment. Guthrie’s father was badly burned in 1927, as Woody himself was in 1952. Fire stalked him, just a few steps ahead of Huntington’s Disease. In his autobiographical novel, Bound for Glory, Guthrie recounts Clara’s death in terms of his devotion to his sister and her own indomitable hope. Dying, she exhibited the kind of optimism Guthrie would later express in so much of his music. From her deathbed, she admonished, “don’t you cry. Promise me that you won’t ever cry” (134). Bryan Garman sees Clara’s ghost haunting Guthrie’s songs. As a child absorbing the folk songs his mother sang in an ever “loster” voice, politics, music, and family trauma mingled for Woody. Listening to his mother’s “hurt songs”, Woody’s imagination fused “Clara’s death, the family’s dire financial situation, and Nora’s deteriorating health” (91) into a vision for his own work.

Guthrie’s art expressed compassion for the suffering as not just a human virtue, but also a political one. His union song “1913 Massacre”, for instance, makes its argument empathetically, recounting an actual event “in which company police incite[d] a riot […] at a union Christmas party” (Garman 182). The facts are grim:

[on] Christmas Eve, over five hundred children and some of their mothers and fathers crowded the hall […]. A short time after 4p.m., someone yelled “Fire”, and a panic resulted […]. A mass of children and some parents scrambled down the stairwell […], got trapped there, and smothered in the press of their own bodies. After the stair was cleared [a witness] “saw the marks of the children’s nails in the plaster, where they had desperately scratched to get free, as they suffocated”. (Jackson 114)

The enormity of the crime is almost enough to choke any response into a shocked silence. However, Guthrie approaches the story from a very human level, focusing on smaller details and individual figures among the 73 victims and their killers. He imagines “a little girl [who] sits down by the Christmas tree lights,/To play the piano so you gotta keep quiet”, even as “the copper boss’ thug men are milling outside”. After the tragedy, “The gun thugs they laughed at their murderous joke,/While the children were smothered on the stairs by the door”. Guthrie must have seen his sister in the image of the little girl who died in a fire. He ends the song not with a call to organize, but with a plaintive lament of regret and despair: “See what your greed for money has done” (Lyrics).

If obfuscation, stonewalling, and silence were the modes Joe Strummer took to address his brother’s suicide, it is no less true that the tragedy shaped his songwriting. In a rare comment on David Mellor’s death, Strummer said, “I don’t know how it affects people” (Salewicz 19). His confusion was genuine, as he also remarked, “I think for him committing suicide was a really brave thing to do […]. Even if it was a total cop out” (69). In 1970, David, 18 months the senior of John, was “found dead on a bench […] in Regent’s park […]. The cause of death was […] aspirin poisoning, following the ingestion of one hundred tablets. The verdict was suicide” (68). John “identif[ied] the body of his brother, which had lain undiscovered in the park for three days” (68). Before his suicide, David had been transformed by radical politics, as his brother later would be. Unfortunately, where Joe Strummer found leftist politics, non-conformity, and compassion, David Mellor discovered fascism and self-loathing. At 18, David suddenly redecorated his room with “Nazi pictures […], swastikas and images of Hitler”. Teenage rebellion is the stuff of rock and roll, and David may have been simply looking for attention; “Perhaps as a rebellion against […] Ron Mellor’s socialism, David […] had joined the National Front, the radical right-wing British political party” (67).

There is no direct line from David’s suicide to Joe Strummer’s art, but at least two major themes in Strummer’s songwriting seem influenced by his brother’s death. Of course, Strummer regularly returns to anti-fascist political reform, not to say revolution, often in attacks on racism and bigotry. Another link to David’s suicide is Strummer’s repeated admonitions to deny death and optimistically, joyfully seize life in the moment. Like Guthrie, Strummer explores politics on a human scale. “Ghetto Defendant” addresses urban despair and the loss of humanity and hope by the masses through the example of a lone defendant. Strummer reminds us that: “It is heroin pity/Not tear gas nor baton charge/That stops you taking the city” (Combat Rock). The nameless protagonist of “Ghetto Defendant” is, as David Mellor had been, overwhelmed by forces too massive and monolithic to challenge or even comprehend. Like David, she disappears into whatever tonic can soothe her pain. For David, it was fascism. For the Ghetto Defendant, who is “Forced to watch at the feast/Then sweep up the night”, it’s heroin. Strummer had long railed against poisoning youthful minds with lies, drugs and hate. “Ghetto Defendant” asserts that drug abuse, far from being subversive, is a powerful tool for stifling youthful rebellion, that it is, in a word, hateful. Twenty-odd years later, on his final recording, Strummer echoes this sentiment asking, “Who’s sponsoring the crack ghetto?” (“Moses”).

Perhaps nowhere in his later output is the fearful power of capitalism captured more poignantly than in “Generations”, his contribution to a human rights benefit album. Strummer imagines the listener as a father “out buying pajamas/For [his] four year old girl”. Finding the clothes “Cheap on the rack”, the father collapses into self-loathing: “Oh, don’t you feel like dirt?/‘Cos you can see into the shack/Where they sewed the shirts”. He captures the despair not just of the nameless worker who “sewed the shirts” but of a father dehumanized by the consumer society in which he lives, forced to be party to abuse and oppression he can only imagine. In essence, Strummer says, “See what your greed for money has done” (Guthrie Lyrics).

Guthrie and Strummer’s compassion focused on identification with the Other. In “White Riot or Right Riot: A Look Back at Punk and Antiracism”, Antonio D’Ambrosio nicely dissects the successes and failures of punk’s – specifically, the Clash’s – treatment of racism. He concludes that “punk’s approach to antiracism […] was far from effective” (184) and that even when successful, punk focused on issues of Blacks and Whites (especially in terms of musical influence) while “racism against Asians, Hispanics, and Jews was essentially ignored” (188). True, punk was hardly a civil rights movement and punk rockers frequently addressed racism naïvely. “White Riot”, for example, likely struck many listeners as a call for white unity against black people rather than with them. But racism is an intricate and intractable problem; addressing it at all leaves one open to all manner of questions. Indeed, when D’Ambrosio writes about “racism against […] Jews” (188), he himself is being naïve; are “Jews” a “racial ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- General Editor’s Preface

- Notes on Contributors

- Credits

- Introduction: John Woody Joe Mellor Strummer: The Many Lives, Travails and Sundry Shortcomings of a Punk Rock Warlord

- PART I JOHN/WOODY/JOE

- PART II I DON’T TRUST YOU

- PART III WHY SHOULD YOU TRUST ME?

- PART IV STRUMMER ON BROADWAY (AND SUNSET)

- List of References

- Index