- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Children and Social Security

About this book

This title was first published in 2003. There is growing anxiety about the consequences of social and economic change for children in industrial countries. It is in this context that the Federation for International Studies in Social Security chose Children and Social Security as the theme of its conference held in June 2001. Leading academics came together to discuss issues such as international comparative studies of child poverty, financial benefit packages for children, aspects of social security provision for families with children. This volume is international in focus bringing together research from the US, Europe, South Africa, New Zealand it should be useful to researchers of social policy, economics, sociology and politics, as well as policy-makers and representatives of charities and international bodies.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Introduction and overview

A review of comparative research on child poverty

- Poverty rates (and the composition of the poor) vary with different definitions of income especially whether it is before or after housing costs.

- The results are sensitive to the general shape of the income distribution.

- Income tends to misrepresent the real living standards of farmers, the self-employed and students.

- Income 'lumping' at points of the distribution where large numbers of households are receiving the (same) minimum income creates big variations in the poverty rate for small changes in the threshold.

- A household income measure fails to take account of the distribution of income within families - especially problematic for those (southern EU) countries with significant minorities of children living in multi-unit households.

- Most analyses report poverty rates, not poverty gaps - how far below the poverty line children are.

- The cross sectional data sets do not allow an analysis of how often or how long children are in poverty (though see below).

- Finally because they are based on survey data these estimates take time to emerge - currently researchers are working on the LIS data for circa 1995 (LIS website), the OECD data is 1993-1995 and the latest published ECHP analysis of poverty is for the fourth 1998 sweep (1997 income data).

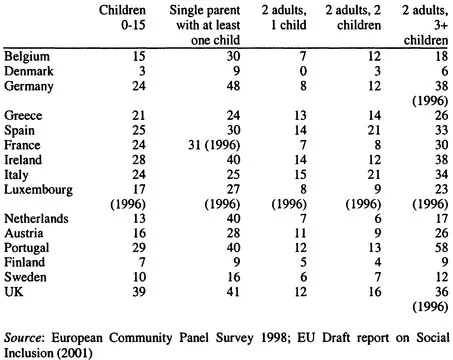

- Child poverty varies considerably between countries. LIS data produces a ranking of 25 countries and shows that the UK, the USA and Russia were top of the child poverty league table in the mid 1990s (UNICEF, 2000). The most recent data on child poverty is from the 1998 ECHP (income data for 1997) and this finds the UK with the highest child poverty rate in the EU by some margin (Table 1, column 1).

- If a less relative threshold is used, such as the proportion of children below the US Poverty Standard then the ranking change. Among the EU countries the southern EU countries and Ireland have the highest child poverty rates (UNICEF 2000).

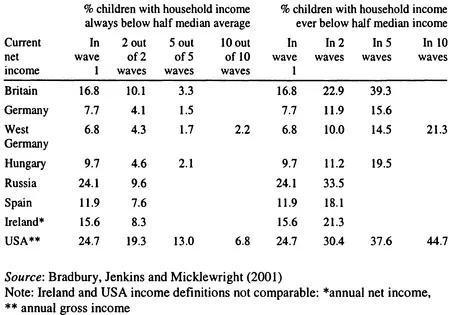

- It is very likely to be the case that where child poverty is persistent it is a harsher experience and with longer-term consequences. Table 2 presents an analysis of the long-term poverty for all households and households with children based on the ECHP. Long-term poverty is defined here as being in poverty (below 50 per cent of median equivalent disposable income) in each of the first four sweeps (income data 1993-1996) of the ECHP. On this definition long-term poverty is very rare in Denmark and rare in France and the Netherlands but it is higher in UK, Ireland, Belgium and the Southern EU countries.

| All households | Households with children | |

| Austria | 2.5 | |

| Belgium | 4.3 | 6.0 |

| Denmark | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Finland | 1.6 | - |

| France | 2.4 | 1.7 |

| Greece | 7.3 | 5.9 |

| Ireland | 3.8 | 4.3 |

| Italy | 4.8 | 5.3 |

| Netherlands | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| Portugal | 8.7 | 6.4 |

| Spain | 3.6 | 4.6 |

| Sweden | 10.5 | |

| UK | 6.5 | 4.3 |

- Nine out of the 15 European Union countries have a higher child poverty rate than over 65 poverty rate, including the UK (see Figure 1).1 Some countries including the UK are special in having comparatively high poverty rates for both children and the over 65s. There need not be a trade-off between child and older people poverty - Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Finland and Sweden achieve low rates of both. However in some countries there may have been a trade off - Denmark has a much lower child poverty rate than older poverty rate and Germany and the UK both have a big gap between their over 65 and child poverty rates. The living standards of their pensioners may have been sustained at the expense of children.

- Not all countries experienced an increase in child poverty between the mid 1980s and the mid 1990s, indeed about half have experienced a reduction (Figure 2). This demonstrates that it is not the case that changes in family form, particularly the increase in cohabitati...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction and overview