![]()

1 The Gap into Governance

MICHAEL J. WHINCOP

Since the 1980s, small medium enterprises (SMEs) have assumed an ever-increasing importance in the growth and development of Western economies. However, the capacity for small businesses to fulfil their potential in an economy depends on the availability of finance. Markets for small firm finance are notoriously problematic — even firms that would be willing to pay a market rate for finance may not be able to get it. Economic analysis attributes this to asymmetries of information, which preclude investors from evaluating the quality of the investment proposed by entrepreneurs, as well as to the difficulty that the former have in monitoring potential opportunism by the latter.

The most successful small firm finance market is the American venture capital market, which has financed some of the world’s fastest-growing high-tech firms, such as Microsoft, Genentech, and a host of Internet-based firms. Despite the venture capital market’s high profile, an even larger informal capital market for small firms exists. These investors are described as ‘angels’. The angel finance market is possibly three times larger than the venture capital market, and often finances earlier stages of a firm’s growth and firms whose growth falls below the returns venture capitalists require. However, we know little about angels, who crave anonymity.

Many policies have been introduced to increase the access of firms to equity finance. These include investment subsidies, ‘public’ venture capital, and especially tax incentives, such as reduced capital gains rates and other concessions for investors in small firms and research and development, in addition to other legal regimes designed to encourage innovation, amongst which intellectual property rights are important. Other policy reforms aim to reduce the costs of capital raising, such as liberalised mandatory disclosure obligations. Governments and private bodies have also attempted to encourage financing by developing technology-based services that facilitate matching of investors and entrepreneurs, or providing a central database of investment opportunities. The premise of this book is that to understand — and thus to achieve — policy reform, attention must be paid to ‘inner’ aspects of small firms. This includes ethical principles for investors and entrepreneurs, the mechanisms of governance in small firms, the conditions that facilitate the growth of trust, and the limits of financial contracting between investors and entrepreneurs.

This introduction outlines these themes. It describes the financing gap that small firms encounter after they exhaust easily accessed funds, but before they can seek finance in a public capital raising. Finance gaps are caused by information and transaction costs. Because these costs are always present in some magnitude, finance gaps cannot easily be ‘filled’. Regulation can distort incentives and impose transaction costs of its own, without diminishing the problems associated with the governance of small firm relations. The book seeks to bring these two elements closer together, by analysing the people, the contracts and the relations that make up small firms, and by closer scrutiny of policy instruments.

The next part of the book concentrates on the structure and governance of the small firm, by studying what the last paragraph referred to as the people, the contracts and the relations. First, it synthesises international research carried out on informal angel finance, which is the least well understood part of the market. Second, this part describes the contracts between entrepreneurs and investors. This illustrates some of the central problems with small firms — uncertainty, information asymmetry, and opportunism — and how in practice these problems are addressed contractually. Third, the analysis of contracts is deepened by explaining how formal contracts are supplemented by informal obligations, governance processes (such as boards of directors), and by affective relations, such as trust. Fourth, ethical issues are studied in detail by showing some of the difficulties associated with institutionalising ethics in small firms. Specific links with policy and regulation are examined in each chapter.

The final part of the book addresses policy reform within small firm finance markets and the legal system. The policy focuses here are initiatives to reduce information and transaction costs by discussing ‘listing’ services for entrepreneurs, disclosure obligations when finance is raised, intellectual property, and income taxation. The essays discuss recent changes, provide international contrasts, and link back to the finance gap by discussing evidence on the relationship between policy instruments and entrepreneurial innovation.

The Finance Gap

There are two imperfections in small firm finance markets: finance rationing and a finance gap. Each arises from imperfect, incomplete information — that is, the parties are not omniscient with respect to their own payoffs and those of the other party. This is an acute problem in small firms, because they face high and imprecise risks. Even a firm that gets the finance it needs, when it is needed, faces unknowns — future demand competition, the entrepreneur’s adaptability, and so on. These unknowns are reflected in the most stylised fact of small business research — the high percentage of business failure. Uncertainty itself is not a barrier to market formation. Price reflects uncertainty by discounting the stream of benefits for the probability that they will not materialise. In a product market, the buyer can demand a lower price. In finance markets, the investor can demand a higher yield. However, a high-yielding investment is just a promise to pay in the future and, given limited liability, that promise is not credible in many future states of the world. It follows that markets cannot clear at particular yields, and the willingness to offer higher yields does not convey information about the quality of the investment. If the market cannot clear, finance will be rationed. Not all those who are willing to pay a particular yield will get finance (Stiglitz and Weiss 1981).

Adverse selection intensifies rationing. Investors may have less information than entrepreneurs about the quality of investments. If investors cannot distinguish good from bad investments, they will rationally demand yields for a project of only average quality. These conditions may induce market failure if the best projects (which take the biggest discount) drop out of the market, followed by the next best of those remaining in the pool, until nothing worth financing is left (Akerlof 1972). This result may be most intense if some investors, such as leading venture capital firms, are capable of ‘skimming’ the best projects, so that the average quality of the remaining investments is lower.

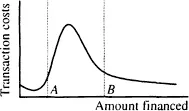

These factors do not explain why finance gaps exist — why there are substantial discontinuities in market density with respect to the amount of finance sought. In Australia, for example, the finance gap lies between $500,000 and $2 million (Marsden Jacobs Associates 1995). The reasons that explain rationing don’t explain why gaps occur. A finance gap suggests that transaction costs are inversely U-shaped with respect to the amount financed. Figure 1.1 sketches its likely shape.

Figure 1.1 Transaction Costs with Respect to Amount Financed

Up to A, and beyond B, transaction costs are relatively low, but they rise to a maximum in the AB region. An economies of scale argument is only partially persuasive, since it cannot explain the existence of a turning point.1 The usual justification recognises that the identity of the investors changes as the amount financed rises. Close to the origin, finance comes from the founder, her family and friends. When those sources are exhausted, ‘angel’ finance is available from informal venture capitalists. At the opposite end, investment will be sourced from public capital markets, when the firm is able to go public. Prior to doing so, it will seek finance from formal venture capitalists. This argument asserts that there is a finance gap because the cost structure that formal venture capitalists face justifies a minimum investment. However, angels, who supply the preceding tranche of finance, invest up to maxima which fall short of venture capitalists’ minima, because of wealth or diversification constraints.

This argument begs an obvious question. If angels face a maximum substantially less than the venture capitalist’s minimum, it does not explain why a second, third or fourth angel might not be introduced to inject the necessary funds. A simple answer might be that angels are very few in number, rationing effects and adverse selection being at their most corrosive when firms first seek external equity. However, this proves nothing about capital availability, but merely explains why capital is not directed to small firms. The most fruitful approach is to think of the finance gap as a product of a distribution of transaction costs that takes a unipeaked form as in Figure 1.1, and to explain such a distribution.

Transaction costs take two forms (Katz 1990). First, there are direct costs of coming to a deal. The sources of these costs include expenditure on due diligence inquiries, legal documentation, the cost of advertising for investors and so on. Second, there are costs of strategic behaviour — the resources consumed by behaviour at the time of and after the contract in order to appropriate the gains from trade. These are particularly important in small firm finance. They include concealing or distorting information at the time of the contract, as well as opportunism by both parties after forming the contract. Opportunism is discussed in later chapters. For the moment, it is only necessary to understand why transaction costs would be expected to be distributed in the form that Figure 1.1 suggests. The direct costs of the deal may be inversely U-shaped because of the high degree of informality in early forms of funding. Friends and family may demand very little contractual protection and may not require due diligence investigation. Early on, firms may obtain external finance in the form of debt. Although the business may not produce cash flows that support debt service payments, entrepreneurs may have personal wealth that can serve as collateral. Debt has the advantage that its costs are relatively low (Williamson 1988), so this is consistent with the low transaction costs close to the origin in Figure 1.1.

Once these sources are exhausted, the entrepreneur will then turn to angel finance to further the start-up. From this point on, capital raising imposes substantial fixed costs arising from due diligence investigations. Angel finance is renowned for high information costs. Angels crave anonymity in order to avoid unwanted attention from governments, which imposes costs on entrepreneurs seeking finance in a way that lacks a parallel with commercial lending institutions. In Chapters 2 and 3, Hindle and Rushworth, and Acs and Prowse document angels’ dissatisfaction with information channels. In addition, the package of rights between the angel and the entrepreneur is likely to give rise to extensive, complex dickering. Moreover, the risk of strategic abuses of these rights (such as the right to sack the entrepreneur) may consume significant real resources. The design of general-purpose governance institutions is also costly. Attracting the right people and creating ethical governance processes takes time and effort, and legal rules that expose directors to liability makes it still more costly. If angels are wealth constrained (as the conventional explanation of the finance gap suggests), transaction costs will increase if it is necessary to assemble an angel syndicate. In those circumstances, angels must determine how they can address problems of collective action, such as free riding, and resolve disagreements quickly. Costs of cooperation can therefore be substantial.

Thus the sudden rise in transaction costs is predictable. The need for entrepreneurs and investors to search for the best matches imposes very high search and negotiation costs. The risks to external investors in equity arising from opportunism, shirking and other strategic behaviour are substantial. The costs of developing the appropriate governance institutions to address these problems and to provide for the structure of future decision making are considerable, and the risk that these institutions may be abused may have a fiercely corrosive effect on the assets of the firm. The costs of cooperation and consent between investors also rise over time and create new risks of opportunism.

I have referred to governance and ethics. We may think of the finance gap as an ethics gap. Close to the origin, the likelihood of opportunism or unethical behaviour is quite low. The sources of ‘pre-gap’ finance at this point are very strongly socially embedded since investors are friends and family (Granovetter 1985). They should be characterised by strong levels of trust and the enforcement of cooperative behaviour by extralegal norms. Although this is less characteristic of a relation with a bank, price competition amongst banks and the rule-governed quality of debt relations reduces the scope of ex ante and ex post opportunism (cf. Franks and Sussman 2000). It is in traversing the gap that problems arise, since the occasion for unethical behaviour is considerably wider. Particularly in the case of angel finance, the likelihood that reputation can function to restrain opportunism is lower, since the entrepreneur may not have much of a future if he fails on this occasion and has little to lose in the way of sunk reputational investments at early stages. Opportunism by the angel is similarly difficult to constrain because of the blurry nature of information in this market segment about players and their propensities. Matters change as the firm approaches point B in Figure 1.1. As venture capitalists come on to the scene, the amount of information increases. The fledgling firm bears witness to some cooperation between an angel and the entrepreneur, and the entrepreneur’s behaviour is increasingly constrained by sunk-cost investments in reputation. It is therefore appropriate to regard ethical and governance problems as a source of the discontinuity in transaction costs that drives the finance gap. For these reasons, essays in this collection focus on this issue in addition to the more conventional economic and legal focuses.

An Outline of the Essays

The first six essays concentrate on the structure and governance of the small firm. Small firm finance is significantly different from corporate finance because of the significance of interpersonal relations and active investing. In Chapter 2, Kevin Hindle and Susan Rushworth synthesise empirical investigations of angel attitudes, behaviours and characteristics in nine countries. They find that simple ‘cookie-cutter’ depictions of angels are dangerous, because there appear to be significant differences between jurisdictions. About all we can say is that angels are male, middle-aged, with managerial (and often start-up) experience, who usually take an active role in the small firm’s business. They prefer to invest close to home, but some studies suggest that this is not immutable. They regard the quality of management as the key variable to success. Other characteristics are more variable. Hindle and Rushworth call attention to the lack of success that governmental policies have had in some countries — perhaps neglecting the personal and governance issues in small firms.

Zoltan Acs and Stephen Prowse’s essay describes the results of interviews with angels. The findings, which broadly support Hindle and Rushworth’s conclusions, indicate that angels take some — but by no means all — of the contract protections that formal venture capitalists take. Their evidence shows that when making investment decisions, angels rely on very basic information channels and, conformably with my claim in this chapter, on whether they or close associates have trusted the entrepreneur. Acs and Prowse argue that there is a role for government in improving the strength of information channels, and describe how the United States federal government has developed the Angel Capital Electronic Network (ACE-Net) to do so. They conclude on a somewhat sceptical note — the importance of personal relations between angels and entrepreneurs may attenuate the significance of reduced information costs.

Michael Klausner and Kate Litvak’s chapter provides a primer on the economics of venture capital. Venture capital investments are made under extreme conditions of agency cost, uncertainty, and information asymmetries. The venture capital firm has a crucial role in monitoring the entrepreneur, and constraining his private incentives to continue with the venture when it has ceased to be justifiable or the entrepreneur ceases to add value to it. Klausner and Litvak describe the contracts that allow this to occur. These include the reliance in compensation schemes on stock that only vests when the firm has succeeded, the use of staged investment in order to discipline the entrepreneur, and the right to veto certain managerial or financial decisions. These powers give...