![]()

Chapter 1

David Bergelson (1884—1952): A Biography

Joseph Sherman

Early Years, 1884–1904

Born on 12 August 1884 in Okhrimovo near Uman in the tsarist province of Kiev, David Bergelson was the youngest of his affluent and pious parents’ nine children. His father, Rafael, was a follower of R. Dovid Twersky, the Hasidic rebbe of Talnye,1 in honour of whom he named the ‘miracle son’ of his old age. Although steeped in Jewish learning, Rafael Bergelson had no secular education: he spoke no Russian, merely enough Polish and, perhaps, Ukrainian to conduct his business. As one of the district’s wealthiest lumber and grain merchants, he made his home a centre for brokers, leaseholders, and landowners. His son David was given an eclectic education that combined traditional Jewish studies with secular subjects taught by a local maskil, enabling the boy to acquire fluency in Hebrew and Russian, in addition to his native Yiddish.

Rafael Bergelson died in 1893, and the nine-year-old David could scarcely remember him in later life. By contrast, his mother, Dreyze, whom he remembered with affection,2 was a modest woman descended from a respected family. Though scantily educated and in poor health, she was an avid reader of the newest Yiddish fiction by such writers as Shomer (Nokhem-Meyer Shaykevitsh, 1849-1905), Yankev Dinezon (1856-1919), and Mendele Moykher Sforim (Sholem-Yankev Abramovitsh, 1835-1917), with a gift for storytelling herself.3 Left alone with his ailing mother in the vast family home, the boy David was overwhelmed by its desolate mood which was intensified by his mother's passing in 1898, when he was fourteen. Still a dependent between 1898 and 1903, he lived with his older siblings, shuttling between their homes in Kiev, Odessa, and Warsaw; the cost of his board and lodging was deducted from his share of the family inheritance. In 1903 he settled with his brother Yakov, a lumber merchant, in Kiev where Bergelson and his wealthy friend Nakhmen Mayzel (1887-1959) — whose mother Khane was the sister of Yakov Bergelson's wife Leye4 — became avid readers of the booklets issued by the Hebrew publishing house Tushiyah, the Hebrew journal ha-Shiloah, and the writings of Nakhmen Syrkin (1868-1924), the founder of Po'alei Zion, the Zionist Socialist Party, which sought to fuse socialism with Jewish nationalism and later embraced the Territorialist movement.5

Although the city of Kiev was specifically excluded from the Pale of Settlement, the official census recorded that its Jewish population increased from 31,800 in 1897 to 81,256 by the end of 1913. Unofficially, it was greater: many Jews evaded the census, while commuters lived in surrounding settlements. Wealthy Kiev Jews included the Brodsky and Zaitsev families whose factories provided large-scale employment; the city was also home to numerous Jewish physicians and lawyers. St Vladimir University had the largest Jewish student body of all universities in Russia, while its Polytechnic Institute was endowed by the Jewish sugar magnate Lazar Brodsky.6 Although Bergelson was intellectually able and artistically gifted — he became an accomplished violinist and a forceful actor — his unsystematic education hampered his attempts to acquire higher qualifications, and he failed to pass the seventh and eighth grades of the gymnazium. As an external student at the university in 1901, and again in 1907-08, he attended classes in dentistry, but passed none of the examinations and gave up formal study without earning a diploma.

An avid reader, Bergelson was attracted to the themes of loneliness and displacement in the Hebrew writings of Ahad ha-Am (Asher Ginsburg, 1856—1927),7 Uri-Nissen Gnessin (1881-1913) — a writer he knew personally in Kiev — and Micah Yoysef Berdichevsky (1865–1921), but his first love was for the stylistic control and psychological depth of Turgenev and Chekhov. Fortunately for his own literary ambitions, his share of the family inheritance freed him from the necessity of earning his bread. While he lived in his brother’s house, he was able to spend most of his time working at his writing, despite the snide remarks of other members of his family.8

Social Upheaval, 1905–1917

The Russo-Japanese War and the ensuing revolution of 1905 disrupted traditional Jewish life. Economic necessity drove workers from the small towns; radical ideas destabilized traditional relationships between social groups, generations, and genders.9 Initially, Bergelson seemed unaware of, and indifferent to, this social crisis. Wealthy and unencumbered, he spent his time reading belles-lettres, taking long walks through the countryside around Kiev, sailing down the Dnieper and theorizing about artistic problems with equally well-to-do companions.10 As he later recalled, when the 1905 revolution spread to Kiev, he knew nothing of the differences between Mensheviks and Bolsheviks and had never heard of Lenin. Equally uninformed about the conflicting agendas of Jewish nationalist parties, he had no interest in the quest for a Jewish homeland. Nevertheless, he followed others, as he admitted, ‘in attending rallies, took part in a few demonstrations, wandered about in workers’ areas, [and] read by chance whatever socialistic literature came to hand'.11 Only slowly, through its effect on people he knew, did he perceive the way industrialization and the rapid flow of new capital undermined the social stability of an order built on inheritance and dowry.12

Bergelson began reading Yiddish literature seriously only after he had started writing himself. Primarily concerned with making his work flow in the mainstream of European letters, he worked first in Hebrew and then in Russian. In 1906 he sent his Hebrew story ‘Reykus’ (Emptiness) to the journal ha-Zman (The Time), edited in Vilna by David Frischmann (1859-1922) and Yeshaye Bershadsky (1871-1910), but it was rejected.13 His pieces in Russian were equally unsuccessful. Among those who encouraged him to turn to Yiddish was Elkhonon Kalmanson (1857-1930), a Kiev-based intimate of Sholem Aleichem (Sholem-Yankev Rabinovitsh, 1859-1916) and Lev Shestov (1866-1938), to whom Bergelson showed some of his Hebrew and Russian sketches. Kalmanson, a tireless promoter of Jewish cultural identity through the development of Yiddish, later perceptively noted that its modern literature was born because young writers like Bergelson longed to identify with their people.14 As the evolving course of his literary life was to show, this became a lifelong commitment for Bergelson.

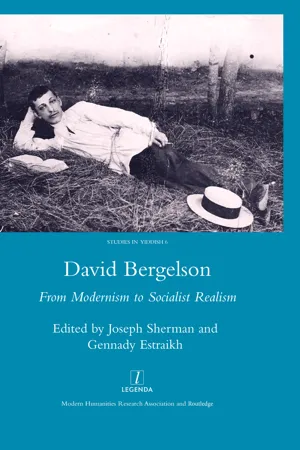

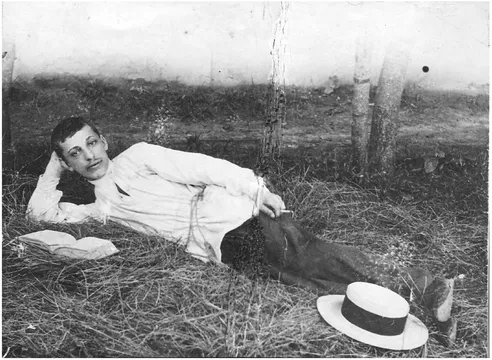

FIG. 1.1. David Bergelson, Okhrimovo, near Uman, around 1905

All the same, he found his transition to Yiddish difficult. In seeking an individualistic diction, he found scant guidance in the work of his immediate predecessors. Mendele’s style seemed to him outdated and, though attracted to his themes, he considered a dead end the Polish dialect of Y.-L. Peretz (1852-1915). Despite admiring the early fiction of Sholem Asch (1880-1957), he rejected Asch’s idealization of the shtetl. Only in the work of Sholem Aleichem, also a native of Ukraine, did he find a Yiddish familiar to him, so his earliest stories in Yiddish — none of them published — took Sholem Aleichem’s style as their model, with disastrous results. Sholem Aleichem’s baredevdikayt, his ‘volubility’, was, as Bergelson himself recognized, useless for his own artistic goals.15 To present the shtetl ’s fading bourgeoisie as individuals rather than as stereotypes, Bergelson had to create his own language. Depriving the third-person narrative voice of its conventional omniscience, he required his readers to infer for themselves the motives of his characters from what they said or failed to say. Moreover, he took pains to foreground this mode of telling, making it self-consciously call attention to itself. Both techniques — the displacement of narrative control and the uncertainty of knowing what is true — marked his work as modernist.16

That this approach was radically new to Yiddish literature and, in both style and theme, was initially unwelcome is demonstrated by the difficulty he experienced in getting his earliest stories published. Two of his first Yiddish works, a story entitled ‘Blut’ (Blood), in which a young woman with revolutionary sympathies inadvertently causes the death of her own father, and a second in which a young man returns from military service to find his wife seriously ill,17 were, according to Mayzel, strongly reminiscent of Chekhov and Schnitzler, and characteristic neither in theme nor in style of what later became Bergelson’s distinctive prose. Submitted to Vilna’s Literarishe monatsshtriftn (Literary Monthly), neither piece received so much as an acknowledgement.18 Bergelson’s first mature Yiddish story, ‘Di drite’ (The third one) (1907), was rejected by Khaym Tshemerinsky,19 the editor of the Kiev Yiddish daily Dos folk (The People), when Bergelson refused to change the tale’s ending, and he had no better success with several other stories, among them ‘Der toyber’ (The deaf man), completed in 1906, which he sent to various Yiddish publications in both Vilna and Warsaw. In 1907 he forwarded it to Hillel Tsaytlin, editor of the Warsaw miscellanies Naye tsayt (New Times), who kept the work on file for more than a year, but finally rejected it. In 1907 Bergelson also sent fragments of ‘Arum vokzal’ (At the depot) — the novella that established his reputation — to Peretz, the sought-after mentor of all aspiring Yiddish writers, from whom he did not receive the courtesy of a reply.

Returned by editors reluctant to take risks, and accompanied by comments veering between tentative admiration and conviction that such texts were ‘too modern’ for Yiddish readers, some of Bergelson’s best stories had been completed by the time he was twenty years old, yet they remained unpublished. Although he had completed ‘Arum vokzal’ in 1908 as a reworking of his rejected Hebrew tale ‘Reykus’, it was only published in 1909 because of Nakhmen Mayzel’s intervention. As Kiev had no Yiddish print shop in those years, Mayzel travelled to Warsaw where, according to his own account, he walked the streets trying unsuccessfully to interest one of the city’s many publishers in the novella. He finally engaged Yakov Lidsky, the founder-owner of the publishing house Progres, to print it; Bergelson personally defrayed half the costs. This agreement concluded, Mayzel sent for Bergelson by telegram:

We both wandered about literary Warsaw and met none of the writers. We were afraid to visit Peretz. On one occasion we came to Ceglana Street, to his apartment building, stood on the steps, wanted to ring the bell, and in trepidation went away again. [...] We thought little of a great many very well-known literary names. We believed that they should yield place to newer, more interesting talents.20

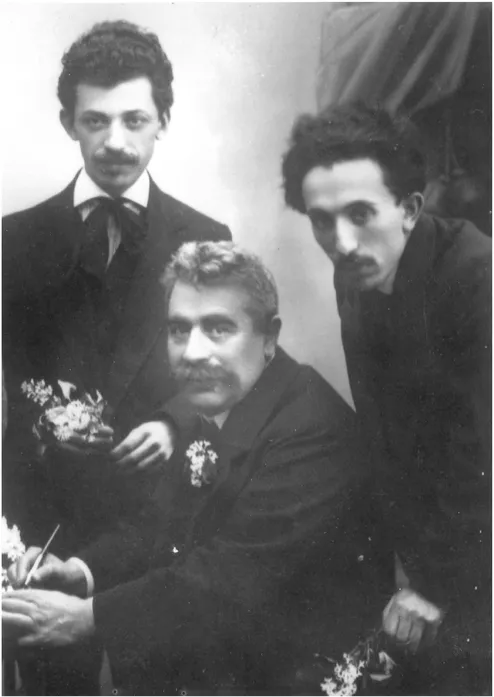

FIG. 1.2. David Bergelson (left) and Yitskhok-Leybush Peretz (sitting), 1910; third person unidentified

When ‘Arum vokzal’ was finally published, its originality was recognized by leading critics including A. Vayter (Ayzik-Meyer Devenishki, 1878–1919), Avrom Reyzen (1876-1953), and Shmuel Niger (1883-1955); Niger discussed it in the St Petersburg newspaper Fraynd (Friend).21 Encouraged by this success, at the end of in 1909 Mayzel established his own publishing house, called Kunstfarlag, which brought out two more of Bergelson’s stories, ‘Der toyber’ (The deaf man) and ‘Tsvey vegn’ (Two roads), in the first volume of Der yidisher almanakh (The Yiddish Miscellany), a publication that Bergelson co-edited and sponsored.22 In a surge of creativity, he published widely in short-lived periodicals both in Kiev and elsewhere. In 1911-12, he gave the stories, ‘Ahin tsu vegs’ (On the way there) and ‘Der letster rosheshone’ (The last Rosh ha-Shanah), to Vuhin? (Whither?), and others to the miscellany Fun tsayt tsu tsayt (From Time to Time), continuing to win critical praise from sophisticated readers.

Although he lived and worked for ten years in Kiev, Bergelson tended to avoid urban settings in his writing. Primarily, he claimed, this was because in the shtetl the bourgeoisie still spoke Yiddish, while in the metropolis they spoke Russian. This was only partly true. A more significant reason was Bergelson’s artistic commi...